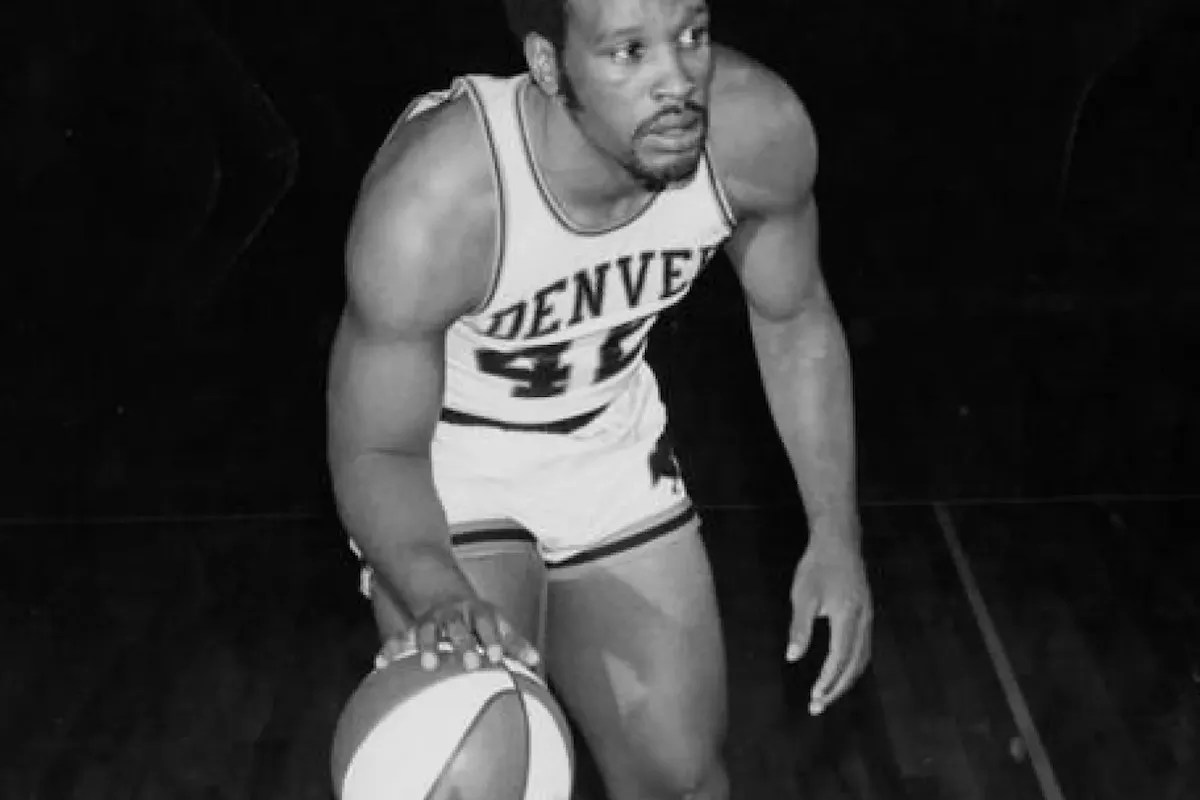

Courtesy of Lonnie Wright Jr.

Audio By Carbonatix

Lonnie Wright Jr. sees the limits of athleticism pushed to new heights all the time.

The University of Colorado’s Travis Hunter is running miles every game, playing offense and defense as a wide receiver and cornerback. Hunter’s coach, Deion Sanders, made a name for himself as the only athlete to play in the World Series and the Super Bowl, exceeding in both baseball and football like the more famous Bo Jackson.

Even so, Wright Jr. has no doubt that his father could have given all these athletes a run for their money. His dad was Lonnie Wright, who played for both the Denver Broncos and the Denver Rockets (now the Nuggets) in the 1960s. And unlike Sanders and Jackson, he played both his sports in the same season.

“They played the two sports, but not at the same time,” he says of Jackson and Sanders. “Basketball is even more hard on you. Baseball is kind of a gimme. He was doing basketball and football. That’s very rare. Now the way the game is set up, basketball is more of an open game, where they kind of protect you. And football is football. There’s a lot of physicality to it, but those guys were brutal back then. Today, he probably could have been one of the greats as well.”

The son of a ranked heavyweight boxer, Lonnie Wright grew up in Newark, New Jersey and went to South Side High School, since renamed Malcolm X Shabazz High School. He came to Colorado in 1962 on a full-ride scholarship from Colorado State University after being recruited by the school’s basketball coach, Jim Williams.

While Wright was at CSU, he also competed in track and field. In his freshman year, he set a school shot-put record of 52 feet and 9 inches, which has since been broken. In basketball, he scored 1,246 points during three seasons and helped the Rams get to an NCAA tournament in 1966.

That year, Wright graduated from CSU and was drafted by the St. Louis Hawks (now the Atlanta Hawks) to play in the American Basketball Association, a professional league that merged with the National Basketball Association in 1976. When the Denver Broncos also approached him with an offer, Wright chose to sign with them instead and play in the American Football League, a professional league that merged with the National Football League in 1970.

“He didn’t even play football in college,” Wright Jr. notes. “He got drafted off his high school record because he was kind of one of those Michael Vick dudes who played quarterback, so he threw for tons of touchdowns and ran for a lot of yards.”

Wright played 26 games as a defensive safety in 1966 and 1967 during two seasons with the Denver Broncos. A year into his professional sports career, the Denver Rockets approached him with a deal to come back to basketball. Wright signed with the Rockets and returned to basketball as a professional in 1967, his last year as a pro football player. He played both shooting guard and point guard in 335 games during six seasons – first for the Rockets from 1967 to 1971, and then two more seasons with the Miami Floridians – before ending his professional sports career in 1972.

Lonnie Wright is the only athlete to play both professional basketball and football in Denver.

Courtesy of Lonnie Wright Jr.

By then, Wright’s son, Lonnie Jr., was three years old. He grew up hearing stories about his father’s athletic abilities, like how he could jump and reach the top of the backboard on a basketball hoop. “Apparently, he was some kind of amazing athlete. I didn’t see, but everybody told me,” Wright Jr. says. “He could do all kinds of things.”

But Wright Jr. could see how sports had torn up his father’s body. “I’m a little traumatized because of watching him take 35, 45 minutes to an hour a day to get out of bed because his body was so beat up,” he remembers. “This man was like handicapped, almost.”

Lonnie Wright’s condition affected his son, too. “You lose a lot of quality time with your parent,” Wright Jr. says. “We were bumping heads consistently, because I would say, ‘You’re all hurt, bro. I can’t see myself doing this.’ At fourteen, fifteen, it was a constant bumping of heads.”

He doesn’t think his father’s athletic achievements were worth the pain. “He appreciated it. If you went to his house, it’s an award shrine,” Wright Jr. says. “But as far as physically, I don’t know if it was worth it. But I asked him, and he said he would do it again.”

Seeing his dad’s physical condition scared Wright Jr. away from participating in sports himself. Instead, he pursued a career “behind the ball.” He wanted to learn how to manage sports teams or athletes, either as a general manager or agent, but instead wound up starting Ascension Services, a commercial cleaning service. He now handles large buildings throughout Denver, including Empower Field, where his crews do deep-cleans of the Broncos locker room and clubhouse.

Lonnie Wright Jr. says that his father paid a painful price for his career.

Bennito L. Kelty

Wright Jr. looks at guys like Sanders, “one of the greatest athletes in history,” and sees that “he can barely walk. Deion is destroyed.” Even great one-sport athletes like LeBron James, “people look at him like he’s amazing. For me, I’m like, ‘This guy is going to be in a wheelchair for the next twenty years.’ He’s going to be walking around like an old man,” he says.

“For most people, it’s all positive, but they don’t see the inside of it,” he adds. “For me, I don’t look at sports the way most people do. I see these concussions, the hurt, bruised bodies, battered. I see all of that, bro. The wear and tear on their bodies.”

Lonnie Wright was inducted into the CSU Athletics Hall of Fame in 1989; he died in March 2012 at the age of 67 from congestive heart failure. “Lonnie Wright was one of New Jersey’s finest student athletes, who excelled in every sport he played,” his wife, Johanna, wrote on a bronze plaque dedicated to him in South Orange, New Jersey. “Lonnie Wright was a fierce competitor, a natural athlete, a life coach with the booming voice of a giant among us. He lived a worthy life.”

In Denver, where his athletic career took place, Wright’s name lives on only through his son, who lives and works here. Wright Jr. considers his father “one of the great unrecognized athletes,” he says, “With advances in physical therapy, I think he would’ve done a little better. It would have been easier for him now. They were more physical, and the refs were more liberal with abuse you could give people.”

But his father played through pain for the love of the game, his son says, not for money or fame.