Three: A Taos Press

Audio By Carbonatix

“I’ve been steeped in all the wrong masculine identities,” admits Colorado School of Mines professor and poet Seth Brady Tucker. “I was taught to admire things that weren’t all that admirable; they’re just normalized by our culture.” Which is the starting point, he says, for his new collection of poetry, The Cruelty Virtues.

The Cruelty Virtues is fresh to the shelves by way of Three: A Taos Press, and both the author and the publisher request that it be purchased not through Amazon and the like, but rather through either of them directly (Tucker here, and Three: A Taos Press here; or from the independent bookstore Prairie Lights Books. The reason is right in line with the collection and its philosophy, made evident throughout, but especially at the end of the book, with the author’s acknowledgements. “You are the hero this art form needs,” Tucker tells the reader. And much of the poetry in this collection explores that idea through character example, both positive and not so much.

Tucker will launch the book officially on February 12 at the Foothills Art Center, 1133 Arapahoe Street in Golden. The event is free and open to the public. Other upcoming local events include a reading and signing on April 3 at Lighthouse Writers Workshop, and on April 11, he’ll read alongside former Colorado Poet Laureate Joe Hutchinson and Madelyn Garner at Tattered Cover.

Melissa Morrow

The poems in Tucker’s collection are wide-ranging, sectioned off by approach in a way: first, the natural world, an easing into the more punctuated observations about men and guns and aggression and masculinity that come in section two. The final section of poems seems more about reconciliation and outcome — a call to action of sorts, reading between the well-crafted lines.

But yes, the focus here is squarely on men and how they operate in their own little fiefdoms, affecting culture and the larger world. The take is evident from the epigraph, a quote by writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit: “Violence doesn’t have a race, a class, a religion, or a nationality, but it does have a gender.”

Tucker’s previous two collections (2012’s Mormon Boy and 2014’s We Deserve the Gods We Ask For) have dealt with similar themes, but he says Cruelty Virtues seems like a natural progression. “Who do we admire in this culture?” he poses. “And should it be these men with what seem to me to be these apeish behaviors?”

An early example of this comes through the poem “Next Door,” which starts with the lines “My neighbor next door rarely/wears a shirt…” and grinds cigarette butts into puddles of driveway oil, shoots fireworks from the hard-packed barren dirt of his weedy backyard, who drinks Keystone and yells everything he says. But it ends with a turn, a poetic volta of a moment in which the narrator of the poem recognizes that “…these boys/never leave the house without hearing their father yell/out the door that he loves them…” It’s a recognizable complexity; a man who remains flawed, remains the victim of his own upbringing, save for one thing he manages to do better for his own kids than his father did for him: express love. “How does that person get built?” Tucker asks. “The kindness, the gentleness is in there. But how does all this posturing come about?”

Another poem later in the book, “Gun Rights,” takes the perspective of a youth raised in a quasi-military family, trained to think of the world in terms of them vs. us — at a moment when the narrator and his family have taken things too far, shown off too many guns and shows of power. The “them” comes for them at the beginning of the poem, and it ends with a cautionary note: in the rifled violence of the scene, the narrator looks at his cousin, who’s still holding onto the foot of a paramilitary grandfather who’s been gut-shot. That cousin is “…crying & ugly; when he begins to crawl away/on his belly, your eyes meet/& only then do you know.” The macho fantasy has been revealed to be just that, in the end. Just play — damaging, chaos-sowing play.

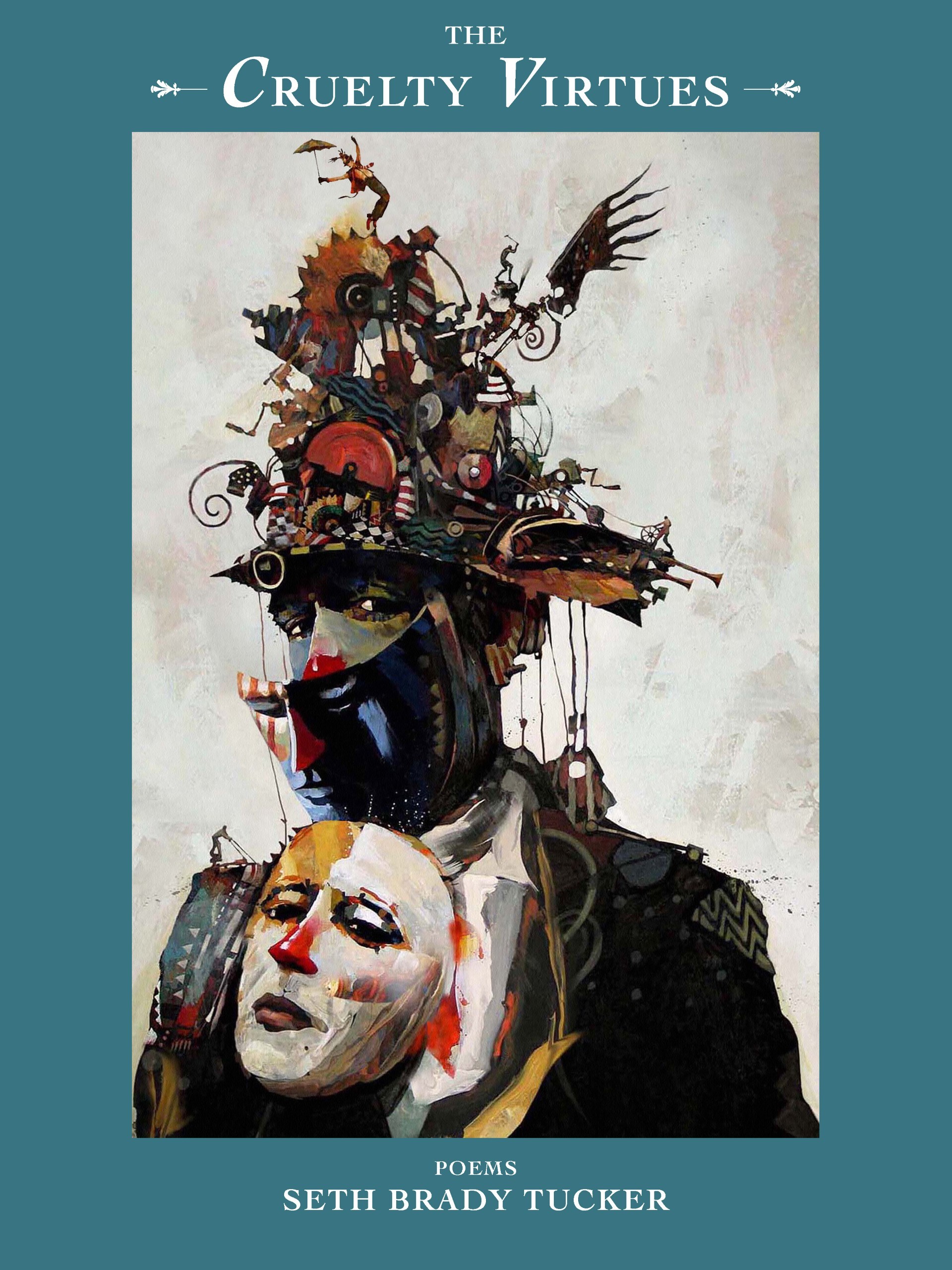

Tucker says that poem is really about a person who gets fooled by the mask that we put on. “It’s one of the reasons I feel so lucky to have stumbled upon Bruce Holwerda’s work” to use as the cover of the book, which portrays a masked figure literally losing his masks, dropping from his face one after another, Tucker says. “This is a character whose masks have failed him. He realizes that too late.”

The upshot of the collection, according to Tucker, is that “I’m impatient for us to be better human beings. I’m impatient for kindness to rise above violence. I’m impatient for empathy not to be seen as a sin. As much as I disagree with my former [Mormon] religion, the people still in it can be wrongheaded, but also tend to be generous and kind. The idea of who we are as humans is not very accurate, ever. So I’m playing with that complexity a little.”

Tucker concedes that the collection can be a tough one to take in at times. “Which is why I scatter some softer pieces throughout and end the collection on a note of hope,” he says. “Those last three poems try to get back to a space where it’s like: hey, we’re not lost. It’s not over yet.“

Seth Brady Tucker’s latest collection of poetry, The Cruelty Virtues, is available now at his website (signed!), the publisher’s, or independent bookstores like Prairie Lights. The free-to-attend launch event will be at 5 p.m. on February 12 at the Foothills Art Center, 1133 Arapahoe Street in Golden.