© Lucas Foglia

Audio By Carbonatix

Thousands of photographs are quietly stored at the Denver Art Museum, carefully catalogued, preserved and, most of the time, unseen. For Eric Paddock, the museum’s curator of photography, that quiet has become impossible to ignore.

“One of the frustrations is that you have all this stuff, and you can’t always share it with the public,” he says. “We do a lot of exhibitions. We do two exhibitions a year; sometimes we’ve done as many as three or four. But often those are things that we borrow from other artists or from galleries or other museums. So I just thought it was time to start getting out some of the stuff that we’ve been collecting.”

That impulse became a series. Last year, the museum debuted What We’ve Been Up To: Landscape. This weekend, the follow-up opens on level six of the Martin Building: What We’ve Been Up To: People, on view February 8 through September 29. The exhibition gathers roughly “fifty photographs plus this big group of 46 pictures that are in the display case back here” from the museum’s permanent collection that have never been displayed in its galleries before.

The show is not organized around celebrity photographers or famous subjects. Instead, Paddock approached the collection photograph by photograph, asking what each image had to say about being human.

and Robert Adams.

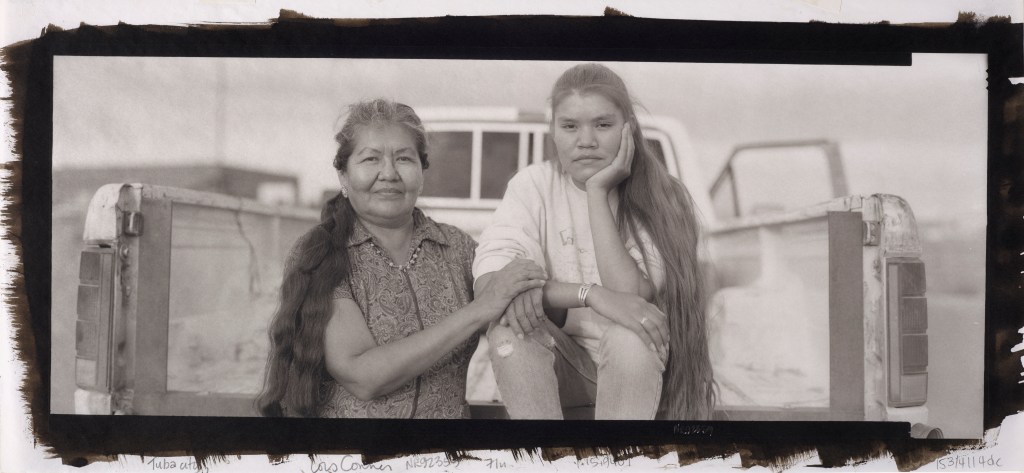

© Lois Conner

“We are looking for good stuff,” he says. “We’ve approached each picture individually, and I wouldn’t say that there’s an overarching plan or philosophy, except to look really carefully and kind of gauge or read what these photographs, in this case, have to say about people and about the joys and the challenges of being human. I was going to say in today’s world, but some of these pictures were made much earlier, so that doesn’t necessarily float.”

The result is a gallery that moves between continents, centuries and contexts with surprising fluidity. A 1912 portrait made in New Orleans by E.J. Bellocq hangs in the same exhibition as contemporary self-portraits, candid street scenes, Polaroids of Andy Warhol and an Irving Penn image of The Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company. Some works are by internationally known artists. Others are by photographers whose names have been lost to history.

“Geographically, it’s kind of wide open,” Paddock says. “There are pictures by photographers in California, Nebraska, Mexico, Pennsylvania, New Mexico, Japan, Mexico and several that we don’t know who made or where they were made.”

© Keisha Scarville

Not every photograph even shows a person. One image by Japanese photographer Yoko Ikeda features only a scattering of pink slippers pointed in different directions. Paddock placed it alongside a sequence of images connected by a quiet visual joke about feet, absence and motion: a long-exposure crowd in St. Petersburg leaving shoes on the steps, a returning prisoner of war on crutches, a patient dancing with his feet cropped out of frame and a woman moving so quickly her leg fails to register on film.

“I don’t really expect anyone to put all that together,” he admits. “It was just my little conceit, as we were figuring out what to include in the show.”

Elsewhere, subtle themes emerge if visitors step back. A wall of children at play gives way to photographs related to food, then to contemplative portraits, then to self-portraits. In one, an artist wears a jacket and tie that match the wallpaper to blend in, creating a visual metaphor for isolation. A quiet Vanitas section nearby features images referencing mortality, such as a life mask, skulls unearthed from an unmarked grave, and corroded canisters of cremated remains from an abandoned hospital.

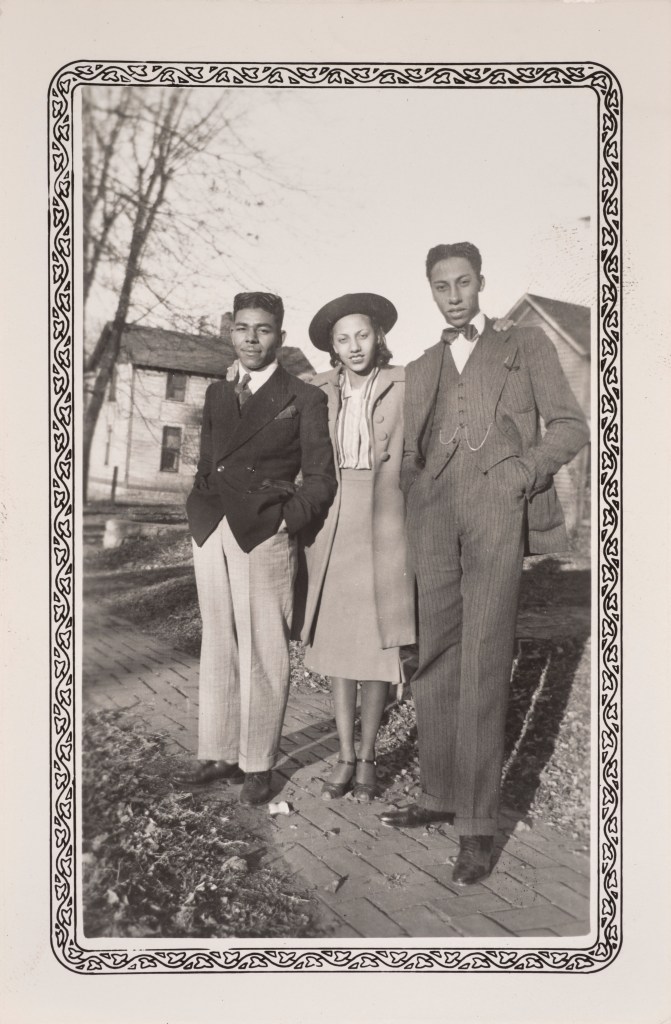

Untitled, Topeka, Kansas, 1924-30. Gelatin silver print; 4 x 2 3/8 inches. Denver Art Museum: Funds from the

Photography Acquisitions Alliance.

Courtesy of Denver Art Museum

“What I would like people to do is I would like them to look at the individual photos,” Paddock says. “But every once in a while, just step back and look at a wall segment.”

The emotional center of the exhibition, however, sits inside a long display case holding 46 small snapshots taken in Topeka, Kansas, between 1924 and 1930. The photographer is unknown. The subjects are Black hotel employees, photographed on a rooftop in their uniforms, then outside on the street and finally in neighborhood scenes with friends and family.

Paddock acquired the images during the pandemic after spotting them in the back of an auction catalog. No one bid on them. He made an offer, rallied a small group of acquisition donors and brought the photographs to Denver in 2020. He’s been waiting to show them ever since.

“Honestly, this might be the whole reason we’re doing this show,” Paddock says. “…I really wanted people to see these. I just think they’re charming; they’re fascinating. For me, they go straight to the heart in a way, and there’s such innocence in some respects.”

In one frame, a man poses stiffly, unsure. In the next, another employee hams it up for the camera, pant cuffs rolled, leaning hard into the moment. In another, a woman appears to dance as the photographer’s shadow cuts across the ground. There are hints of personalities, relationships and inside jokes, frozen in silver halide nearly a century ago.

“Each of these pictures, you look at the people and the way they pose and the way they look at the camera and the way they sort of manage their uniforms,” Paddock says. “They’re all just like these little hints at those people’s personalities. And to me, each one of these people, as you look at the picture, becomes absolutely real and individual.”

For Paddock, the deeper lesson of the exhibition is something photography has taught him over decades of looking.

© Alexey Titarenko

“Looking at photographs, I kind of learned that people don’t change that much,” he says. “Everyone kind of wants the same things. Everyone fears the same things and that’s part of what it is to be human.”

The idea that we are all the same regardless of time, geography or circumstance is what unites the exhibition.

“The idea is to show a lot of different kinds of people, different ages and different backgrounds and we’ll talk about them individually,” Paddock says. “We are doing this as a way of reminding ourselves and the world that we’re all in this together.”

What We’ve Been Up To: People is on view from Sunday, February 8, through Tuesday, September 29, at the Denver Art Museum, 100 West 14th Avenue. Parkway. Learn more at denveratmuseum.org; the exhibition is included in general museum admission.