Denver Art Museum

Audio By Carbonatix

A Constant Sky is appropriately named: The latest exhibition at the Denver Art Museum is an endless vista of imagery, colors and themes.

A quick walk through the gallery of colorful artwork by Andrea Carlson (made from the mixed mediums of oil paint, acrylic paint, gouache, colored pencil, watercolor and ink) is like going outside, looking up at the sky and spinning around until you get so dizzy you collapse in the grass.

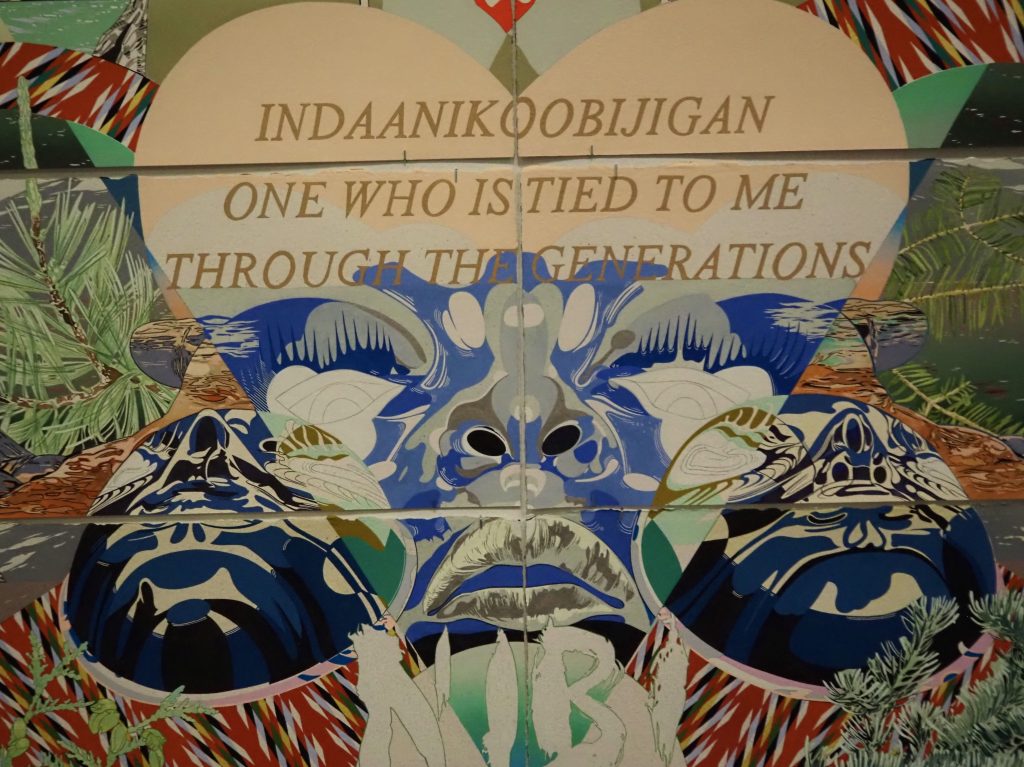

The larger works comprise smaller paper pieces that line up to form a continuous horizon over a body of water that washes up metaphors for motifs like access, denial, power and possession. Carlson’s work is full of cultural critique and theory, but the more personal “Ancestor and Descendant” might be her favorite piece in the show. “I feel like I put a lot of myself in it,” she says. “…That one has much more of my kinship in it.”

Kristen Fiore

But Carlson’s kinship is everywhere in the exhibit on Level 1 of the DAM’s Hamilton Building, from her interest in film to her connection with the ever-changing mood of Lake Superior, which she lives off of in northern Minnesota. The artist is a descendant of the Grand Portage band of Ojibwe as well as European settlers, and her work challenges injustices created by settler narration through references to text, animals, art objects and cultural belongings. Carlson’s work is collected by the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Gallery of Canada, the Walker Art Center and more.

Kristen Fiore

A Constant Sky, which opened October 5 and will stay through February 16, features thirty works — the most comprehensive show of Carlson’s art yet. “I don’t think I’ll ever be able to see this much of my work in one place again, because it is work on paper and is very fragile and hard to get out into one place,” Carlson says. “It’s such an incredible privilege for me to be here in this space and have all the work together.”

The show is one of the final pieces of the DAM’s 100th anniversary celebration of its Indigenous Arts of North America collection. At the beginning of the year, the museum opened Sustained, an exhibition created collaboratively with Indigenous community members about things like family, beauty and humor, which have sustained the community over the past century.

Kent Monkman’s History is Painted by the Victors show this summer was the largest exhibition of Indigenous art at the DAM outside of its permanent Indigenous gallery. The museum recently held its 36th annual Friendship Powwow, which was the first new program created after SCFD passed; at the end of October, the museum will host its Triennial Symposium for Native Arts, where Andrew W. Mellon curator of Native Arts John Lukavic says diverse voices will help set the tone for the next 100 years.

The DAM’s collection is one of the largest accumulations of Indigenous art in the world — while most museums in the 1920s were prioritizing European art, the DAM set itself apart by acknowledging the cultural and artistic significance of North American Indigenous communities. The museum continued collecting contemporary Indigenous art through the decades, unlike other institutions, which frequently regarded Indigenous art as artifacts or ethnographic objects.

Kristen Fiore

During opening remarks at a preview for A Constant Sky, Christoph Heinrich, the DAM’s Frederick and Jan Mayer director, said that it makes sense to end the year with a contemporary exhibit — not artifacts, but living, breathing work.

“Some aspects of it get us to look at the intersection of time and space,” Lukavic says of Carlson’s art. “You think of a film reel on a cell, if each cell were a landscape, and that landscape slowly morphs and changes as you go from cell to cell. She is rendering time and space in a two-dimensional medium.”

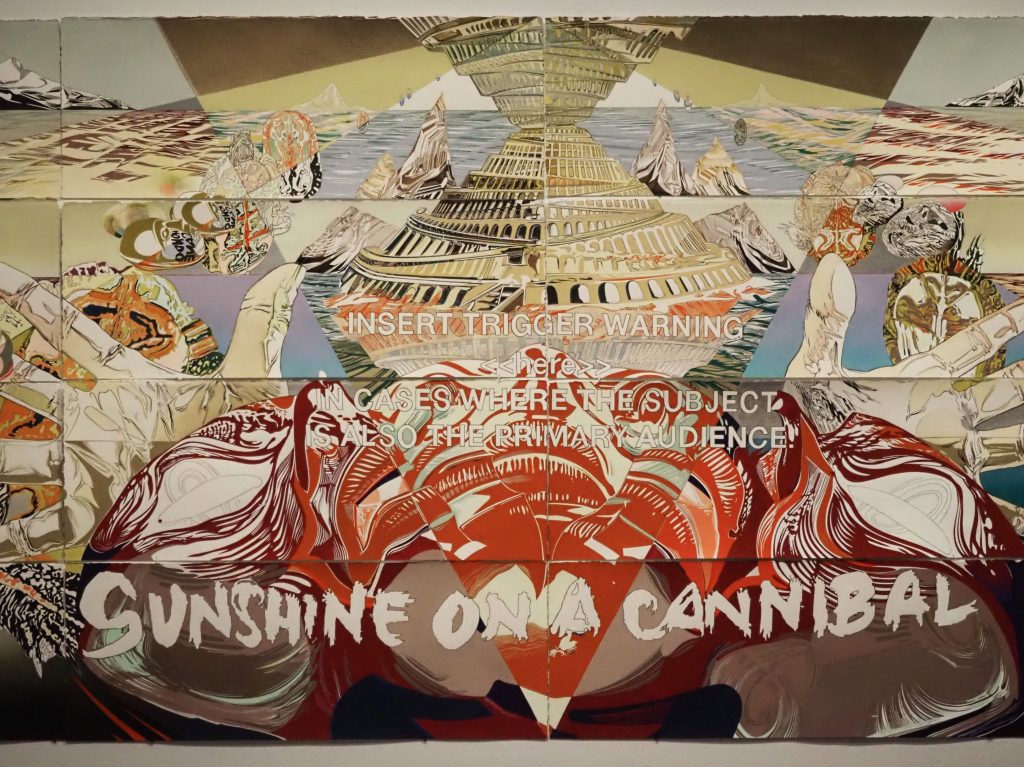

Carlson’s cinematic influences are also films themselves. In A Constant Sky, the “VORE” series references films of the Italian cannibal boom genre of the 1980s, where colonizers would come to Indigenous land in places like Africa or South America and do something horrendous to the local population. “And the films end with the native folks cannibalizing the foreign colonizer,” Carlson says. “These were fantasies. They were horrors, but they still were fantasies that were feeding a colonial narrative of fear of the other.” The “VORE” series metaphorically connects these horror films to the Wiindigo, an insatiable cannibal figure found in Anishinaabe storytelling, calling the movies out.

Kristen Fiore

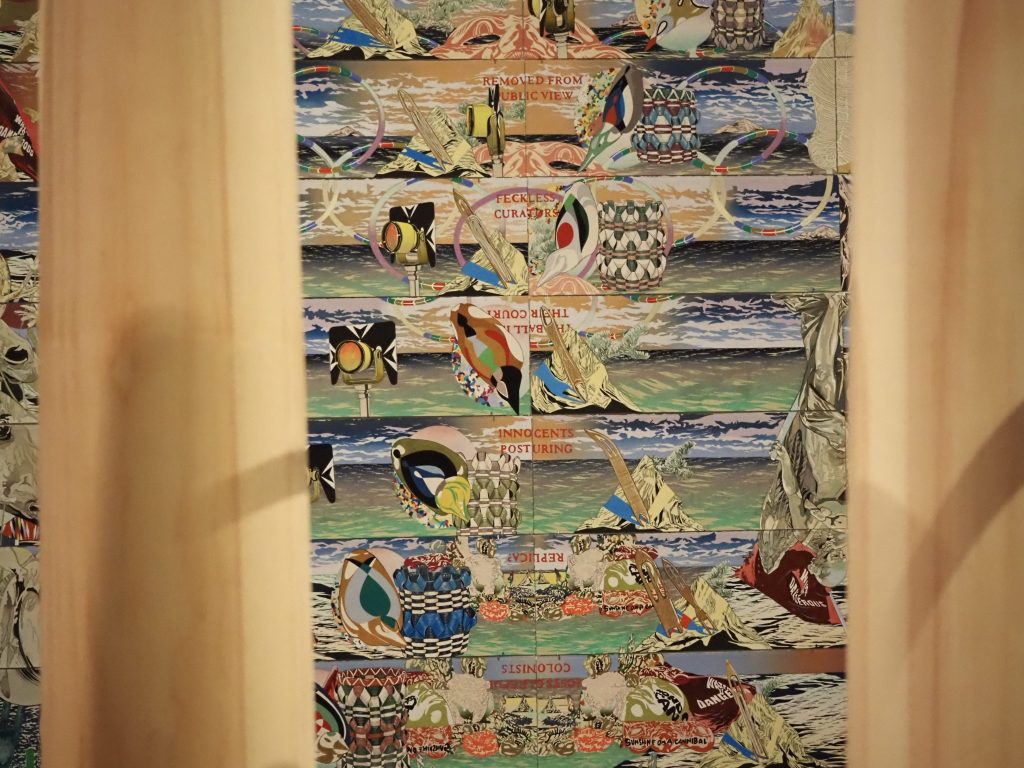

Carlson’s art calls out museums and repatriation, too, with paintings relating to the consumption and greed of colonization as well as museums’ collecting practices and narratives of possession and ownership. In “The Constant Sky,” a commissioned work for the DAM, Indigenous and Western artifacts clash in a stormy body of water where phrases like “Removed From Public View” and “Feckless Curators” line up in the middle.

“She uses items from Western culture as surrogates for cultural belongings that don’t belong in a museum that maybe have been or should be restituted to communities, or that are off view and in storage, because maybe they’re culturally sensitive and shouldn’t be seen, and you’re questioning whether they should even be in a museum in the first place,” Lukavic explains. “…It’s getting us to all be very reflective on the way you think of and approach things that you find in museums.”

“In this piece, I’m thinking more about deep time, legacies and things that keep pushing themselves forward that we have the power to end,” Carlson says.

As a member of the Illinois State Museum Board, Carlson fought to have 6,000 ancestors in the state’s collection repatriated. “Those were really hard meetings,” she says. “I was challenged, I cried at board meetings, I wrote letters. It was very hard. They’re in the process of repatriating the ancestors there. It’s hard, emotional labor, but I have access to these institutions and these spaces, knowing there is a fraught history.”

Her art comments on access, as well. In two different locations, “Columns for a Horizon,” wooden sculptures displayed in front of the art, give visitors a different viewing experience. “Imagine you’re driving down a road right along a beautiful landscape, but there’s always these trees that are in the way, and they’re kind of flickering as you go by,” Lukavic says. “You’re trying to take a picture from the window, but you can never get it quite right. That bubble of frustration of not being able to take in the totality of the landscape is intentional.”

Kristen Fiore

As visitors move through the gallery, they’ll get hints of the artwork behind it, but never the full picture. “Every time you move, they’re obscuring something else in the gallery,” Lukavic says.

“You can imagine yourself in the space, but you can’t get there from here,” Carlson adds. “You can hallucinate it on the work, but there is denial to emerging into that 2D space.”

Dakota Hoska, former associate curator of Native Arts at the DAM and now the curator of Native Arts at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., had been working on the show before leaving the DAM. “Don’t try to decode it,” she recommends. “Enjoy the confusion.”

Carlson wants people to leave A Constant Sky feeling inspired and a little bit challenged. “I hope it makes them want to read the labels or puts a question in the back of their head that sparks a curiosity,” she says.

It may take several visits for the work to even begin to sink in. If you get motion-sick, remember to keep your eyes on the horizon.

“Through metaphor, she’s getting at the core of important ways of seeing the world around us, that if more people were cognizant of, we may have a more respectful way of interacting with each other,” Lukavic says. “…I hope people take the time to explore the work, look for these metaphorical references and read the interpretive text. We don’t tell people what things mean. We try to guide them into seeing landscapes in a different way, about connecting with the world around us, because we are of one world, of one constant sky.”

Andrea Carlson: A Constant Sky is on view at the Denver Art Museum, 100 West 14th Avenue Parkway, through February 16. It is included in general admission.