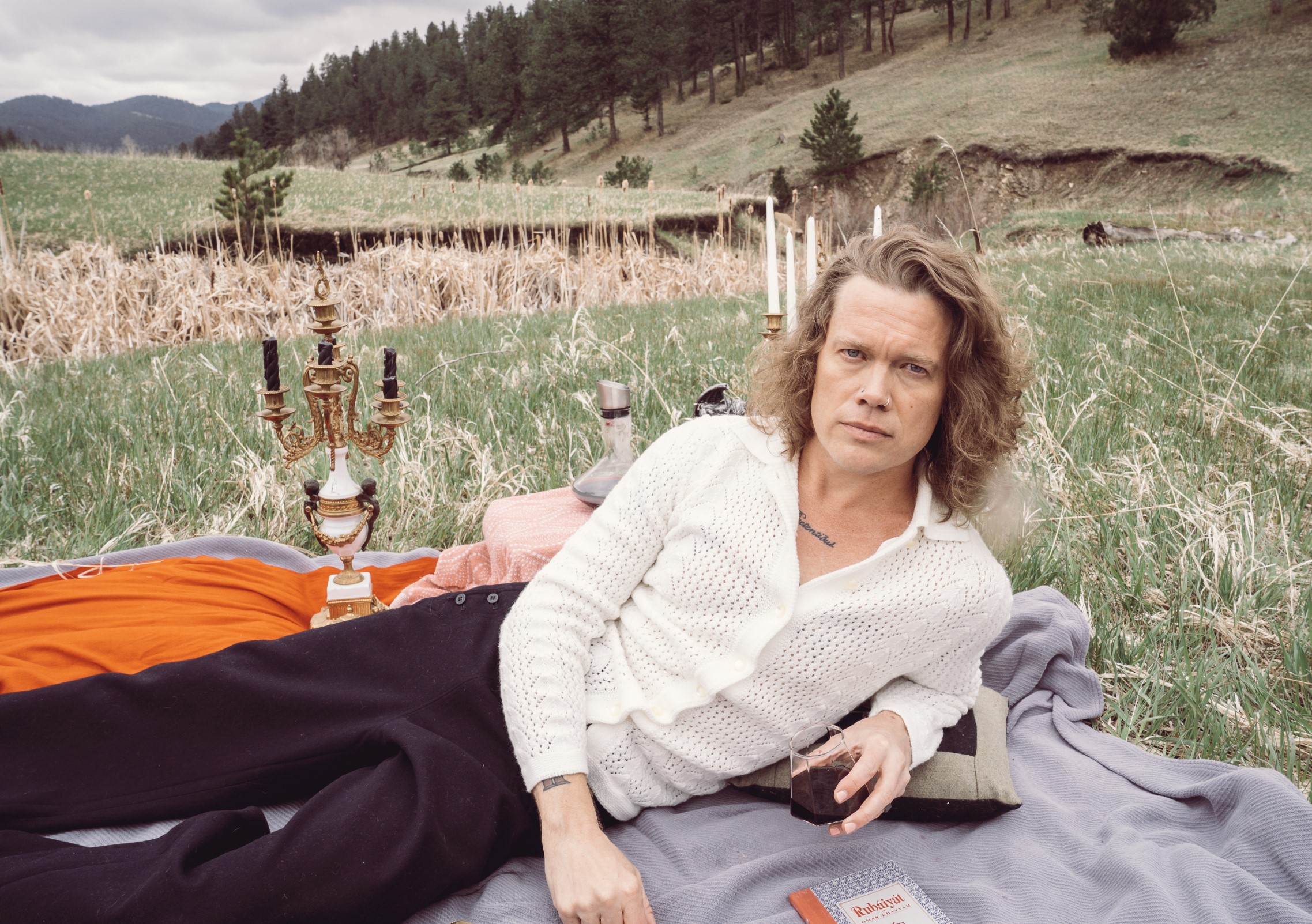

Glenn Ross

Audio By Carbonatix

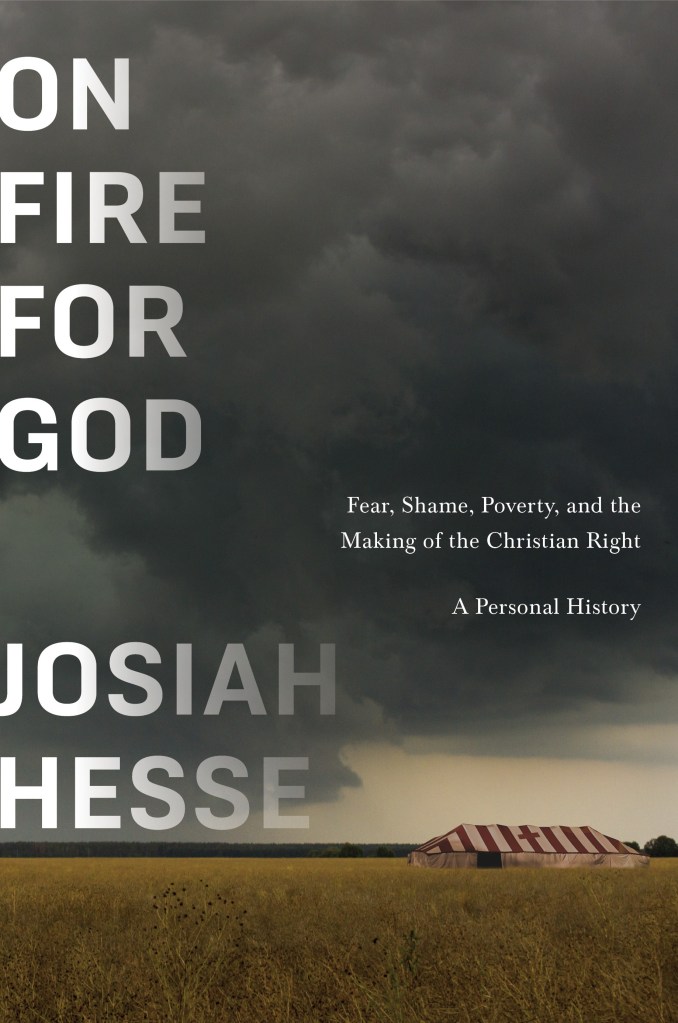

Denver writer Josiah Hesse starts his memoir with a quote from Antonin Scalia, though he prefaces it with the disclaimer that he disagrees with nearly everything else the late Supreme Court justice said. But on this point, they come together: “…some very good people have some very bad ideas.” And that idea — that confluence of the social and political Right and Left — is really at the heart of his memoir, On Fire for God.

It’s a message that’s sadly becoming more and more important — and perhaps tougher and tougher to remember — in today’s America: that we’re going to have to somehow get back to a place where people can recognize what’s happened for what it was, recognize the good in people who may have done, or at least supported, some very bad things, to be able to move forward as a country. It’s one reason why Hesse’s book is being positively reviewed by publishing powerhouses like Kirkus and Publisher’s Weekly, and why the author will be at the Denver Press Club for a conversation with Ryan Warner at 6:30 p.m. on Friday, January 16, which will be recorded for an episode of Colorado Matters.

Pantheon Books

But to Hesse, a longtime Westword contributor who also wrote 2021’s Runner’s High: How a Movement of Cannabis-Fueled Athletes Is Changing the Science of Sports, it’s also just his story. After all, writing a memoir is an act of bravery in itself. “Especially when you’re dealing with fear, childhood fear,” Hesse explains. “The things that freaked you out as a kid, those aren’t necessarily universal — or at least that’s the concern when you’re writing. I went to some pretty intimate places in this book, and the worry was always if people were going to feel what I’m feeling in that moment. But even if people didn’t grow up with religious extremism, they remember what it was like to be bullied. To be scared at night.”

The book is being favorably compared to previous books that attempted to explain the spiraling of America into its current state over the last few decades or more — works like Tara Westover’s Educated, or even Vice President J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. Not that Hesse eagerly accepts the comparison to the latter.

“It frustrated me that Hillbilly Elegy got the reputation it did, for explaining working-class evangelical support for Trump,” says Hesse. “Vance was not working class; he grew up middle class in the suburbs of Ohio. He wasn’t a hillbilly. But also, he was just regurgitating all of the same talking points from the Reagan era, that people need to stop using drugs, start going to church, pull themselves up by their bootstraps. It made no attempt to analyze the social and political landscape and how people have been disenfranchised economically.”

When Hesse set out to do just that, he admits he had a “very convenient” built-in allegory for what he wanted to say: The Music Man. Hesse grew up in Mason City, Iowa, a town so straightlaced that it stood in as the paragon of American small-town cliche River City in Meredith Willson’s hit Broadway musical. It’s a detail that Hesse uses to narrative advantage, helping to explain the simultaneous charm and danger inherent in lockstep tradition, especially when an outside agent waltzes into town with a smile hiding a sneer meant to use a population’s own faith and character against them.

“I started seeing all of these parallels with what I would consider the grift from the Christian Right,” Hesse says. “Professor Harold Hill is a guy that plays on the fears of a community: modernism, big-city vice. He has a low-key racism that isn’t overt, but it’s effective. He starts off the story by arriving in town and asking what trouble is brewing. When he’s told there isn’t any, he replies that he’ll have to create some. He ends up leading citizens to spend what little money they have on a boy’s band that doesn’t even exist.”

It’s very much like President Donald Trump, Hesse says: “What Harold Hill and Trump have in common is that they’re both marketing geniuses.”

Hesse wanted to make that comparison but, at the same time, use his own personal history as anecdotal evidence regarding the socio-economic factors. “It was an ambition of mine to tell that story,” he says, “and place me and my family at the heart of it to weave through that narrative. And also give people an idea of what it’s like to grow up in the sort of religious extremism that sees a young person preparing for the apocalypse, identifying changes in your body as demonic presence. I wanted readers to not just understand it intellectually, but to feel it viscerally, like you would a Stephen King character.”

Of course, The Music Man is a story of redemption — not an arc that many expect Donald Trump and his cronies to enjoy, or even to invite. “There’s this great line at the end when Harold Hill says that for the first time in his life, he got his foot caught in the door,” says Hesse. “He’s fallen in love, not only with the town librarian but with the town itself. There are moments in the play in which there are these sparks of humanity. He discovers that he wants to offer something of value to this town, to these people. I can’t imagine Trump having that kind of moment of self-reflection about his impact on the world. He’s in the business of Trump, first and always.”

Josiah Hesse

The opportunism of the Christian Right isn’t just limited to a mirror of Trump’s rise to power. It’s also about the “capital T and that rhymes with P, and that stands for pool” sort of fear-mongering falsity that creates problems that don’t — or shouldn’t — exist in a community of faith.

“Trans rights, immigrants, the Deep State, Americans on welfare, gay marriage, the War on Drugs, the Satanic Panic,” Hesse ticks off a list of issues that too often stand in for more pressing and real problems. “Abortion is maybe the perfect fit for that narrative. Roe v. Wade was passed in 1973, and evangelicals didn’t give a shit about it until at the earliest 1978 when it became the opportunistic motivator for Jerry Falwell and Paul Weyrich. They used that as the pool table that was coming to town and going to destroy everything good.”

It’s not a new story, Hesse admits. “Throughout history, if you turn up the volume on fear and anger, you’re going to draw a large crowd,” he says. “Nuance and complexity and unity among people might be the necessary nutrients for society, but it won’t make you rich. That’s why a lot of these liberal mainline churches are dying, because they don’t have the theatrics. They don’t embrace the hysteria. That’s why so many churches are now being turned into condos.”

But again, On Fire for God is less about the larger case that it makes for America, religion, politics and control. It’s very much an intimate and fearless revelation of Hesse’s early life and how it shaped him. “Getting people to understand what it’s like to inhabit the skin of a young, terrified evangelical boy,” Hesse says, “hopefully has an even greater impact than academic research can.”

Josiah Hesse will be at the Denver Press Club, 1330 Glenarm Place, for a conversation with Ryan Warner at 6:30 p.m. Friday, January 16.