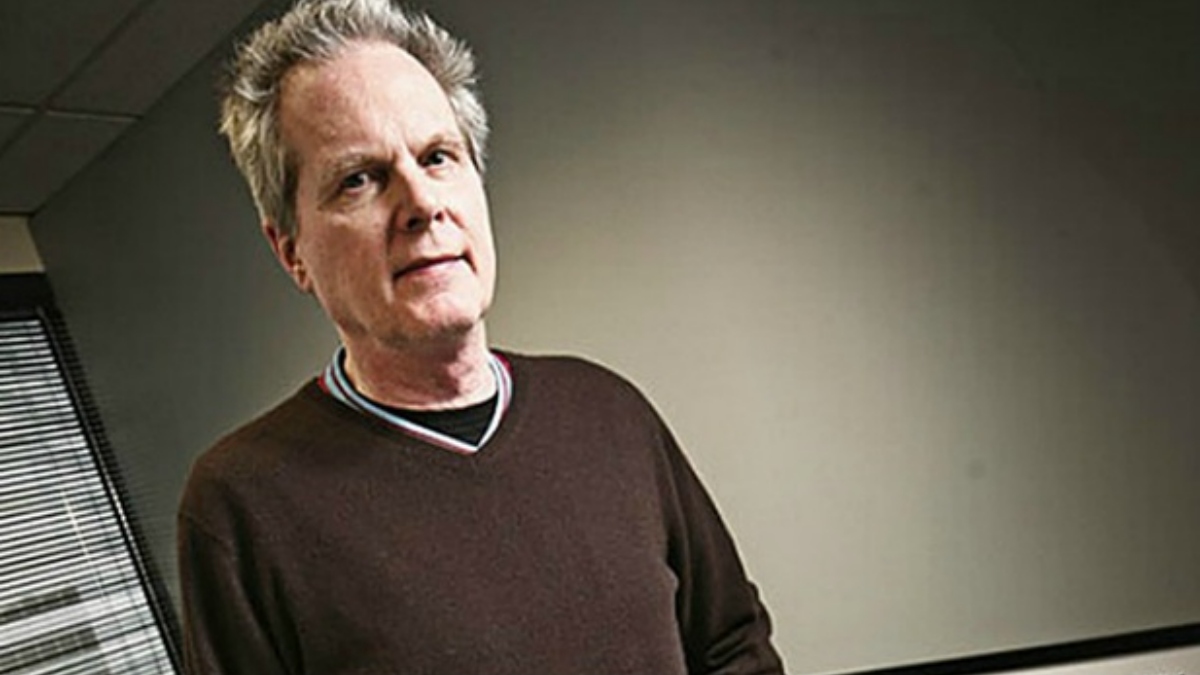

Anthony Camera

Audio By Carbonatix

The movie business is renowned for the story behind the story — the behind-the-scenes drama that’s often more compelling than the action on the screen.

It’s appropriate, then, that Donald Zuckerman‘s exit from his longtime position as Colorado film commissioner remains cloaked in mystery. Among the intriguing clues that a rich narrative lurks just out of view is the fact that Zuckerman’s disappearance wasn’t announced in the sort of formal fashion befitting a figure of his stature. Instead, Eve Lieberman, executive director of Colorado’s Office of Economic Development and International Trade, the governmental branch that employed Zuckerman, revealed the change in a private and notably terse email to officials and film-industry types sent a full week before the news leaked to the greater public via a September 22 article in the Denver Post. (That email is below.)

Thus far, Zuckerman has declined to speak about the development to Westword or any other media outlet. Moreover, the only response to our inquiries offered by OEDIT communications director Alissa Johnson is a statement that lacks both warmth and the slightest personal touch. It reads: “Donald Zuckerman no longer works for the Colorado Office of Economic Development and International Trade. Deputy Film Commissioner Arielle Brachfeld will be filling in as Interim Film Commissioner and Interim Director of the Colorado Office of Film, Television and Media. Also for your awareness and on background, we are not able to comment on personnel matters.”

The timing of the move is even more curious. After all, Zuckerman, who has headed the Colorado Office of Film, Television and Media since 2011, notched his greatest personal accomplishment as film commissioner in March, when the folks at the Sundance Film Festival announced that the renowned event would be relocating from Utah to Boulder. At present, the state is busily gearing up for Sundance’s inaugural Colorado edition, slated for January 2027.

Plenty of politicos have claimed a share of the credit for this coup. But it wouldn’t have happened without Zuckerman, who had been working on facilitating the fest’s shift for the previous two years. The key connection was Sundance board vice chair Gigi Pritzker, an old friend of Zuckerman’s with whom he produced Green Street Hooligans, a 2005 film starring Elijah Wood.

Hooligans is hardly the only notable film on Zuckerman’s résumé. His IMDB page lists 25 production credits, including several that demonstrate his close ties with some of Colorado’s most powerful politicians. In 2009, he helped put together Hick Town, which focused on how future Colorado governor and U.S. Senator John Hickenlooper handled the 2008 Democratic National Convention during his stint as mayor of Denver. Nine years later, Hickenlooper appeared in 2018’s Governors Get It Done: The National Governor’s Association, which directed a flattering spotlight on the organization. And 2022’s Democracy vs. The Big Lie: The Truth About Mail-In Voting features current Colorado Governor Jared Polis, U.S. Senator Michael Bennet and Colorado Secretary of State Jena Griswold.

Despite having so many friends in high places, Zuckerman wasn’t particularly successful when it came to his dealings with the Colorado Legislature. As part of his duties as Colorado film commissioner, he tried to encourage movie companies to bring productions to the state. But he was hamstrung by the refusal of state senators and reps to approve the sort of sizable tax incentives that lure studios — and as a result, pictures that could have been made in Colorado regularly navigated to other, more generous states.

In a 2016 interview with Westword, Zuckerman talked about the situation in the context of that year’s remake of The Magnificent Seven, a Denzel Washington-starrer that lensed in New Mexico instead of Colorado — and he certainly understood why. “New Mexico spends $50 million a year on film incentives,” he said. “We’ve been spending $3 million.”

He added: “I’m the film commissioner, and I would like to see us step up our game. It’s not entirely up to me. We need the governor’s office and the legislature — in particular, the legislature, which really allocates all the funding — to want to do this. Because we’re losing productions that would love to shoot here.”

When asked to speculate then about why Colorado’s General Assembly seemed disinterested in offering up more bucks, Zuckerman admitted, “There’s a certain hubris here. When I first came to Colorado five and a half years ago to start this program, I’d talk to people and they’d say, ‘Of course, they’re going to come here. We’re Colorado. We’re more beautiful.’ Well, nobody had come here in five years at that point.”

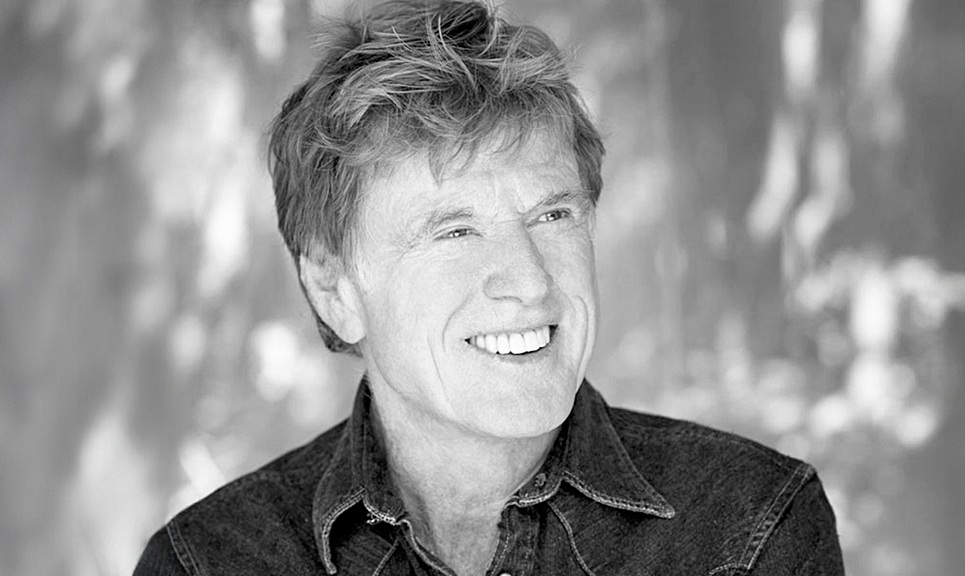

Zuckerman can be forgiven for forgetting about the filming of 2009’s Imagine That, a bomb for Eddie Murphy. But his point was well taken — and even his victories could be turned into defeats. Note that Sundance Film Festival founder Robert Redford came to Colorado to shoot the Netflix offering Our Souls at Night in 2017, in part because of $1.5 million in incentives made available through the Colorado Film Commission. But the following year, Zuckerman confirmed in another Westword interview that Redford wanted to make his next movie in Colorado, too, but decided against it when he learned that no economic incentives were available.

Courtesy of Sundance Film Festival

“Robert Redford went to CU,” Zuckerman pointed out, “and he had a good experience on Our Souls at Night. About a year ago, maybe less, we got a call from his executive producer saying he was perhaps interested in making the next picture he directs here. It was supposed to start this winter, and they wanted us to tell them what we could do with incentives. But after we said we couldn’t give them anything, we never heard from them again.”

By then, Zuckerman had become all too familiar with such conversations. In 2017, the commission’s incentives budget had been cut to just $750,000.

The situation has improved since then. In 2024, Polis signed a bill allowing producers to receive up to $5 million in refundable tax credits per annum for the next half-decade – and the legislation also upped the cap on incentives from 20 percent of local spending to 22 percent. In all, the package authorized production tax credits up to $50 million through 2029.

However, these amounts are dwarfed by the moola offered to film companies by many other states. New Mexico currently has an annual tax-incentives spending cap of $120 million, or 24 times larger than Colorado’s, and Georgia eschews a cap entirely. In 2022, Georgia’s tax credits grew to $1.3 billion, or around triple the $420 million caps in New York and California that year.

No wonder the list of movies at least partly filmed in Colorado is so short. The film-incentive page on the Colorado Office of Film, Television and Media showcases posters of the aforementioned 2017 Redford item Our Souls at Night, plus The Hateful Eight, Furious 7 and Cop Car, all of which premiered in 2015. Moreover, the office’s most recent press release about a film production in the state was issued way back in February, and its focus, The Man Who Changed the World, boasts a budget of just $14.5 million. That’s a little under the $15 million spent on average to make one Game of Thrones episode during the program’s final run in 2019.

But if Zuckerman needed a win, the Sundance-to-Boulder leap provided one.

Of course, Redford’s death on September 16 means he can’t be on hand when the festival bows in Colorado — and the aforementioned email from OEDIT executive director Lieberman, distributed to what she refers to as “partners” at 8:31 p.m. the previous day, September 15, puts Zuckerman’s attendance in severe doubt, too. Here’s the email in its entirety:

Hello Partners,

I am writing to inform you that Donald Zuckerman is no longer employed at OEDIT. Arielle Brachfeld, our Deputy Film Commissioner will be stepping into the role of Interim Film Commissioner immediately, until January when the position will be posted following the end of the state hiring freeze.We appreciate your partnership, and value the work you do with the Colorado Office of Film, Television and Media. If you have any questions, please reach out to Arielle or myself.

Best,

Eve

If anyone has gotten more answers to their questions than Lieberman’s email provides, they’re not talking yet. But there’s a good chance the main players in this scenario have quite a story to tell.