Wes Magyar, Courtesy of MCA Denver

Audio By Carbonatix

Clark Richert, a giant in Colorado’s contemporary scene, is the deserving focus of two simultaneous exhibits: Clark Richert in Hyperspace, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, and Clark Richert: Pattern and Dimensions, at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art.

When the MCA was founded in 1996, a major goal was presenting important shows dedicated to significant Colorado artists like Richert. However, the MCA, like the Denver Art Museum, has done so far too rarely, particularly in light of all the worthy talent in the area. Putting the MCA back on track is Clark Richert in Hyperspace, which was ably realized by assistant curator Zoe Larkins, who talked with Richert and also researched archives, libraries and other sources in order to tell his story and find all of the art she wanted to include in the exhibit. Though Richert had a mother lode of early works stuck in the nooks and crannies of his house and studio, pieces from the 1980s and ’90s had scattered to the four winds, landing in private, corporate and public collections. Surprisingly, corporate and public collections typically do not have overseers, so in a few cases Larkins really had to work to track down the Richerts she was looking for. Adding to the challenge: Richert himself had trashed or abandoned many pieces as he moved his studio around over the decades.

Psychedelic posters by the imaginary

Wes Magyar, Courtesy of MCA Denver

Those moves are definitely part of the story. Richert was an intrinsic part of the counterculture of the 1960s and ’70s, which flourished in Colorado. He came to the state from Kansas in 1963 for graduate study at the University of Colorado Boulder with then-pattern painter George Woodman. By 1965, though, he’d left to help found Drop City, the short-lived though long-renowned artist community – read: commune – located outside of Trinidad. Drop City was envisioned as a suite of domed structures based on Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic structural concepts but freely interpreted by Richert and his fellow communards, resulting in some highly original interpretations of the idea. While some mistakenly think that the “drop” in Drop City refers to dropping out,or dropping acid, it’s actually the name for a performance piece in which incongruous things were “dropped,” literally or figuratively, into a public place. Drop City was vacated in 1969, and Richert eventually returned to Boulder to complete his MFA. In 1974 he co-founded another art collective called Criss-Cross with fellow artists interested in exploring tiling and tessellation patterns.

When news happens, Westword is there —

Your support strengthens our coverage.

We’re aiming to raise $50,000 by December 31, so we can continue covering what matters most to this community. If Westword matters to you, please take action and contribute today, so when news happens, our reporters can be there.

The chronological retrospective at the MCA fills a trio of galleries on the main level as well as the entire second floor of the museum. It begins with “Blue Room,” a painting done in 1964 that’s a geometric rendition of an interior space, with a cruciform defining the picture plane. This play between the depiction of recessive space and the flatness of the canvas’s surface occupied Richert over his career. Sometimes he exaggerates the flatness, at other times the illusion of three-dimensionality, with any number of hybrids in between these opposites. The second gallery holds a revelation: the weird comic book “Being Bag,” done collaboratively with fellow Droppers Gene Bernofsky and Richard Kallweit. While “Being Bag” struck me as an aesthetic non sequitur in the arc of Richert’s oeuvre, its narrative concerns someone passing from one dimension to another, a conceptual underpinning of his work. More on point aesthetically are the glow-in-the-dark patterned posters mass-printed in 1968 under the pseudonym Clard Svensen. I loved them.

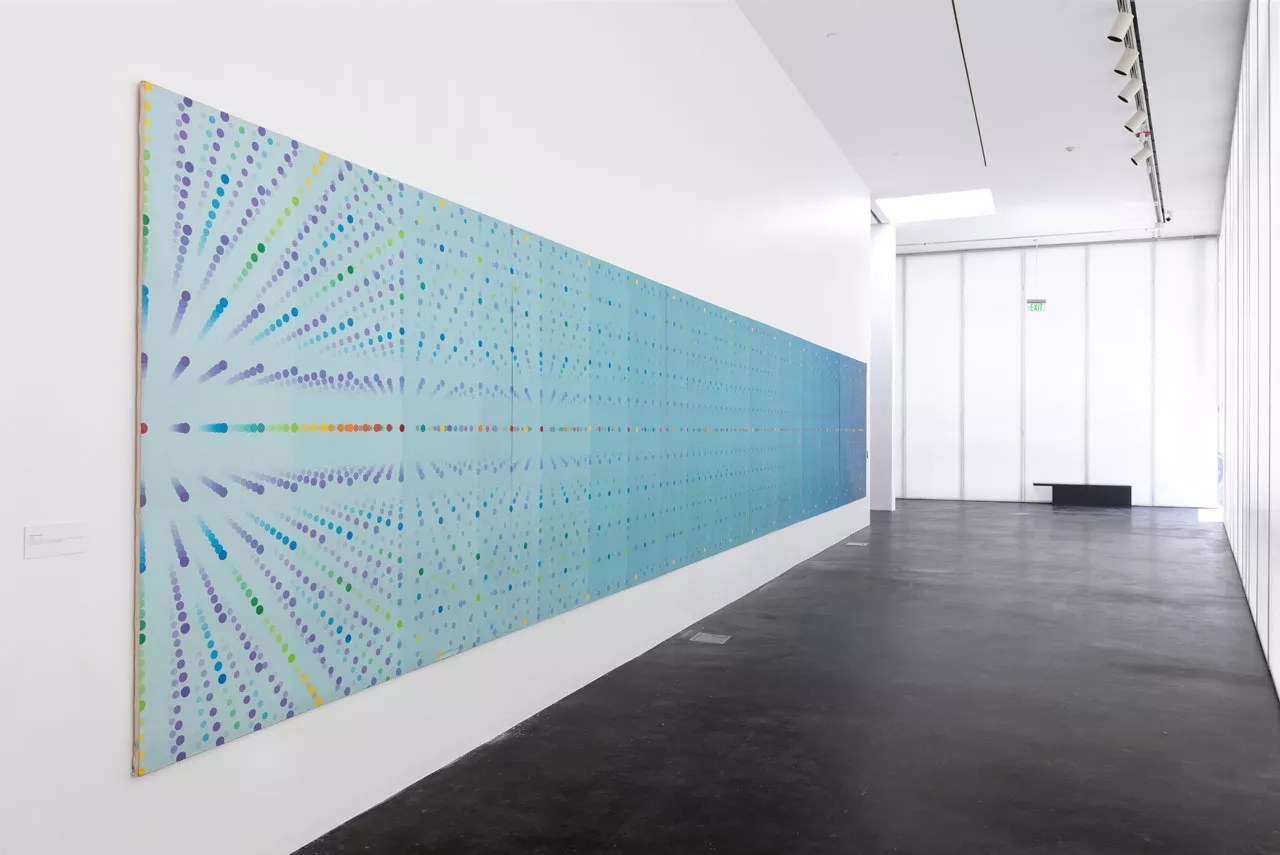

“Horizon Event,” a 42-foot long mural created in 1986, in

Wes Magyar, Courtesy of MCA Denver

The last of the main-floor spaces holds Richert’s Criss-Cross work – unbelievably tight and dense pattern paintings of tiny lines and rectangles done in the late ’70s and early ’80s that were high points of his output. The ultimate extension of this kind of geometric abstraction is on the second level: “Horizon Event,” a 42-foot-long multi-panel mural from 1986 comprising a blue field with variously colored dots arranged so that they appear to recede in space. It’s a showstopper. Larkins told me that when she located the piece, it was in terrible condition; someone had put smiley faces in black Sharpie in the center of many of the lighter-colored dots.

One of the principal second-floor galleries showcases Richert’s paintings from the late ’80s and early ’90s. These hark back to “Blue Room” in that they capture interior spaces, though they’re much more ambitious and complex; Richert populated them with the geometric explorations that had occupied him since his Drop City days, but he employed realism to do it, even rendering a figure in one. By the late 1990s, though, his compositions had gone non-objective again, picking up the threads of his Criss-Cross days. Aside from “Horizon Event,” which anticipates his later minimal depiction of three-dimensionality, the pieces from the past twenty years are generally looser and airier than the earlier pattern works. For these newer paintings, Richert used digital techniques to make his studies, which he didn’t do with the earlier pieces…even if it often looks like he did.

Installation view of the west gallery in

Wes Magyar, Courtesy of BMoCA

The way in which Richert has been exploring the same ideas for nearly sixty years but coming at them from different directions is the focus of BMoCA’s Clark Richert: Pattern and Dimensions. It was curated by Cortney Lane Stell, director and chief curator of nomadic museum Black Cube, who is guest-starring at BMoCA. Stell had curated a Richert show before and has a longstanding relationship with the artist; she even understands the abstract math and physics explored in many of his paintings, which I absolutely do not. But you don’t need that understanding to appreciate the paintings on purely visual grounds.

Stell conceived of the show as a set of separate presentations exploring Richert’s oeuvre. She’s even restaged a couple of the “droppings,” in particular “Pendulum,” a boot on a rope hanging from the building that was initially done by Richert with Bernofsky before they came to Colorado.

“A.R.E.A.” (left) and “Drop City” in

Wes Magyar, Courtesy of BMoCA

The main gallery’s walls are lined with paintings, some from as early as the 1970s and ’80s, but dominated by 21st-century examples, those airy linear patterns based on digital studies. Also included are what Stell calls “Pictorial Investigations,” representational views of specific sites. Of particular interest is “Drop City,” which has a depiction of the artist community running across the top above rectangles that enclose separate images represented in individual perspective views. Even more traditional is Richert’s current conception of a utopian community, “A.R.E.A.,” an aerial view of a village that almost looks like a Grant Wood.

In the front section of the east gallery are some unexpected abstract-expressionist works that Richert did in the early ’60s. On the other side of that gallery is a thoughtful presentation on Drop City, with photographs of various parts of the complex as well as day-glo paintings that inspired the psychedelic posters at the MCA. The paintings look even better than the posters, especially since Stell put them in the dark under black lights. The space also includes a non-narrative film Richert did while studying with legendary vanguard filmmaker Stan Brakhage, and a re-creation of a circular spinning work called “The Ultimate Painting,” which was done by the Drop City crew and later lost. Upstairs, Stell displays a set of prints that look like book pages, laying out Richert’s concepts of space from one dimension to ten. There’s also an interactive feature with Zometool components, which are used to make geometric solids with beams and spherical connectors. Stell pointed out to me how important these Zometools were in creating the shapes of Richert’s patterns, in particular the shadows they cast that align with shapes the artist uses.

The summer of 2019 is clearly Richert’s high season, and these stunning exhibits prove it.

Clark Richert in Hyperspace, through September 1 at MCA Denver, 1485 Delgany Street, 303-298-7554, mcadenver.org.

Clark Richert: Pattern and Dimensions, through September 15 at BMoCA, 1750 13th Street, Boulder, 303-443-2122, bmoca.org.