Social justice drives Cleo Parker Robinson Dance productions. And the company's latest, Rise and Resist — an evening of five dance numbers including pieces from 1947 as well as contemporary works — is no exception. It covers a wide swath of history, including stories about the lifelong struggles of entertainer James Brown, murders by the Ku Klux Klan in the Reconstruction-era South, and the current Syrian refugee crisis.

Cleo Parker Robinson, a Denver icon, founded her dance company in 1970 in the city's historically black Five Points neighborhood; her company is one of the last community institutions to survive in the now largely gentrified area. At the heart of the dance ensemble and academy is a commitment to preserving and teaching the traditions of African-American dance.

"We're committed to an idea, and it's an ideal," Robinson says as she takes a break from fine-tuning the choreography for "The MOVE/ment," one of the dances in the program. "It's about our commitment to peace, harmony, everybody's well-being and everybody's opportunity for access to whatever brings us joy."

"The MOVE/ment" was created by Robinson and premiered earlier this year at the Tour de Force concert, a collaboration with the Colorado Ballet and contemporary dance troupe Wonderbound. The project highlighted how different bodies — black and white, those of ballet dancers and those of modern dancers — can unite for a common purpose.

Robinson created "The MOVE/ment" after visiting Alabama in 2018 to memorialize the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Back home in Colorado, she realized, few people were thinking about the fiftieth anniversary of his murder.

She reflected on the ways that artists such as Aretha Franklin were on the front lines of the civil rights movement. Not only did they march, but they created art that became emblematic of the struggle. As an artist, "you're another kind of soldier," Robinson says. "A soldier for justice."

After reflecting on King's death, she knew there was another dance to be created around civil rights issues. Instead of choreographing it alone, she took a cue from the activists themselves and created "The MOVE/ment" collaboratively, asking dancers to show their physical interpretations of words like "social justice" and "respect."

"The MOVE/ment" serves as a metaphor for how the civil rights movement itself happened. "It looks like chaos for a moment, then it aligns," she says, describing the dance. "That's what the movement was like."

Out of the chaos, the dancers connect with each other one on one, but they ultimately come together. In the end, there is joy, celebration and dancers lifting each other up.

"We can elevate somebody else. We're not putting anybody down," Robinson says. "That type of soaring movement comes naturally to dancers. We're always trying to fly."

Dance, as an art form, physically parallels marches and civil rights struggles, she notes. Like activists, "we're sweating together. Sometimes our feet are bleeding. Sometimes our toes are bleeding." And during strenuous classes and rehearsals, sometimes dancers feel as though they're dying.

But the dances can be just as emotionally taxing.

Cleo Parker Robinson Dance performs its fall program Rise and Resist at the Newman Center for the Performing Arts on September 21 and 22.

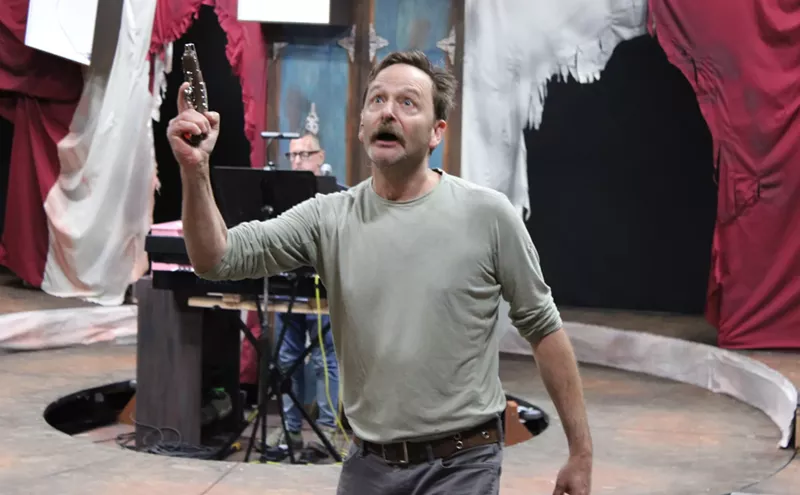

Jerry Metellus

Abel points to the final dance of the program, "Crossing the Rubicon," which is also the last piece created by legendary choreographer Donald McKayle before his death in 2018. "Rubicon" tells the story of the Syrian refugee crisis; in it, dancers embody the risks that refugees take while searching for safety — finding safe passage, leaving others behind, wondering whom to trust.

"There's a pleading and desperation," Abel explains, and the dancers have to convey that. "That's mentally exhausting, which manifests itself physically. You have to give it all away."

Cleo Parker Robinson apprentice Edgar Aguirre studied with McKayle at the University of California, Irvine, during the time he created "Crossing the Rubicon."

"He was big on stories," Aguirre recalls. McKayle instructed dancers to find tender moments within the chaos of the dance. He also required students to read and write about the stories they told through dance so that they could more completely convey the gravity of the works.

"A great way to start is definitely researching," Aguirre says in describing his process. Because the international refugee crisis has shifted culturally and geographically over the years, Aguirre continues to read and collect stories about the issue. "This is how we can manifest these emotions."

While a program that covers a KKK murder, the civil rights movement and Syrian refugees obviously takes on political issues, "the company is not built on a political message," says associate artistic director Winifred R. Harris. "It's built on the human experience."

As she explains, the power of dance lies in helping audiences connect with the emotional reality of social issues, not political discourse.

"They might be changed because they felt something, not because they thought something," Harris says.

Rise and Resist will be performed at 7:30 p.m. Saturday, September 21, and Sunday, September 22, at the Newman Center for the Performing Arts, 2234 East Iliff Avenue. Tickets, $38 to $48, are available at newmantix.com.

Correction, September 17, 2019: An earlier version of this story stated Cleo Parker Robinson Dance was founded in 1974. In fact, it was founded in 1970 and incorporated as a nonprofit in 1974.