Courtesy William Matthews

Audio By Carbonatix

Stock Show season brings Western art to town alongside the livestock shows and rodeos, but in 2020, one of Colorado’s brightest and most successful Western artists, veteran painter William Matthews, has a gritty exhibition of paintings of and about steel mills and the blue-collar aesthetic on view at his studio gallery in RiNo.

That’s just one example of the artist’s versatility, a fact of his creative life that’s often overshadowed by his popular images of cowboys and life on the range, recently monumentalized in a massive public-art mosaic adorning the new Dickies Arena in Fort Worth, Texas. But Matthews has also illustrated album covers and painted scenes from around the world during more than fifty years of making art.

Matthews shared some of that experience with us by answering the Colorado Creatives questionnaire, revealing an independent, satisfied man who’s made the most of all of life’s opportunities.

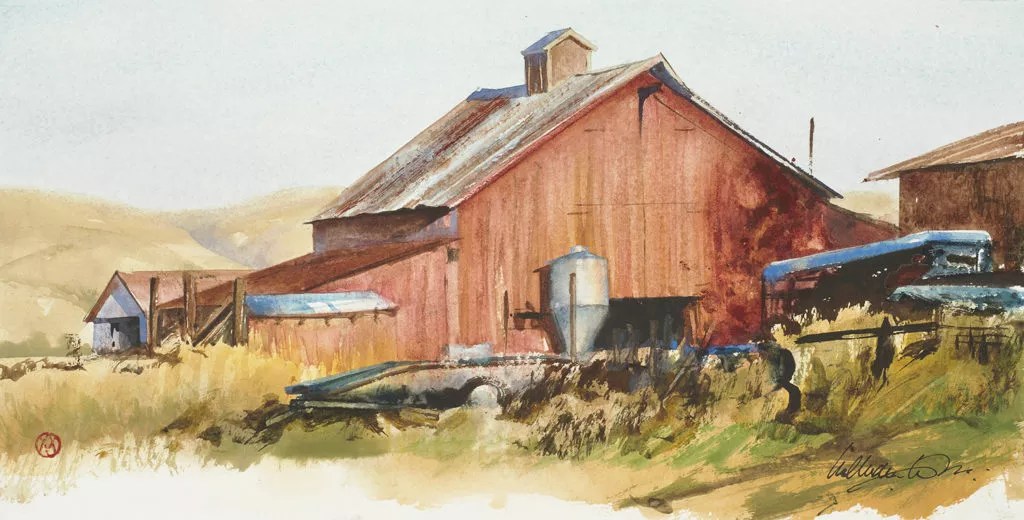

“Halfred’s Barn,” 2016.

Courtesy William Matthews

Westword: What (or who) is your creative muse? What inspires you to sit down and paint?

William Matthews: I’m known for my paintings of cowboys, horses and the Western landscape, but people don’t know that I also love architecture and industrial buildings. Right now, I have a show of paintings of steel mills, the steel-making process and how the steel is used.

I’m not a linear artist. Most people on a road wind and curve up and down, but generally that road is identifiable. The road I’m on is less predictable. That process is not arbitrary – there are just lots of different ideas that don’t necessarily link arms in ways that are predictable.

My interest in projects and art comes from a lot of different places and inspirations. Painting certainly has been one of them. But I like to use different materials, though I’m best known as a watercolorist.

I once did a big show of giant neckties. It really was a painting show, but the neckties were also giant pieces of sculpture. People got confused when they saw it that way, and not as a continuum of things I’ve done in the past that have to do with painting. I love the idea of mixing things up, like using sculpture as a vehicle for something unpredictable.

I have ideas all the time. You try some out, others you don’t, and you end up doing the ones that continue to speak to you more loudly. Eventually you have to answer and acknowledge that call. As an older guy, I don’t want to have not done some of these ideas. I can look back and know I’ve checked off those boxes. Fortunately, I have the energy and the infrastructure, and incredible people who work for me and help me actualize these ideas. I could never do it without them.

What made you pick up a paintbrush in the first place?

My mother was the painter. She was a serious painter. She was actually really good, and all of us were inspired to do artwork early on. My younger sister is a landscape oil painter, and I have another sister who’s an interior designer. My brother in New York is an architect – a really good one. We were all inspired to do artistic things by our mother and grandfather, who was also a painter. He traveled all over the world, gaining a broad knowledge and understanding of art, and he inspired me and my sisters and brother.

Watercolors always spoke to me – must’ve had something to do with my mom being an oil painter and me always being the contrarian. To this day I’m drawn to watercolors – transparent works on paper. Some speak that language and others don’t. People are generally good at one but not necessarily both.

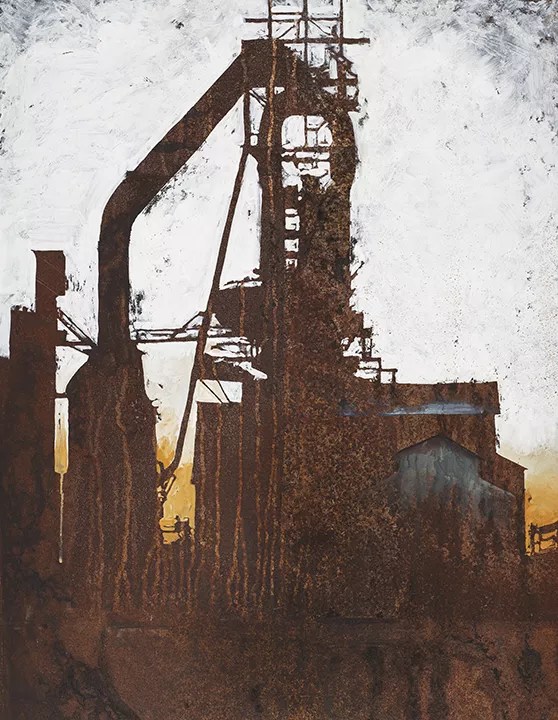

“LeHigh Valley Breakdown,” 2019.

Courtesy William Matthews

Talk about the work in your new show, Steel.

I went to Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh in the ’60s. I was there over a summer taking a course in painting when the steel mills were all running, and I became enamored with those buildings: The sounds, the smoke and activity all got under my skin. I started painting those buildings, and dreamt about what they might look like inside. After pulling some strings, I got some guys to allow me access inside one. That’s when I knew I had to do a show based on that world. It’s not linear at all – it’s not just about the steel-making process. It’s also about how the steel is used, what the material is.

People in the realism world generally paint pastoral images. That’s the vernacular of plein air. I’ve been painting on site since I was five years old. It’s a subject that’s beautiful, but it’s not enough. I wanted the show to be a reaction against that pastoral world.

I find the gritty side of life compelling; it’s part of the American story, but we talk about it now more in terms of yearning for the past. But it still exists. It’s still active now, though it’s more automated – there are more robots doing the work. I’m interested in working men: the blue-collar, hardworking world. That’s what also drew me to cowboys. They’re people who really work hard with their hands, and I have a lot of respect for those men and women and the work they do. They don’t get much societal respect these days. I think that’s unfair.

I’ve been working on this project for many years. The projects that are most important have to percolate for quite a while. Paintings of barns and all things pastoral are a lot of work, but there’s no real thread to it. That doesn’t interest me. I like to see an idea.

In this show, the paintings are about steel, and some of them are painted on patinated, rusted steel with steel frames. It’s not modern art, not conceptual MCA material. It’s not necessarily abstract, though a lot of paintings I do are. In the critical world and its acknowledgments of art, things have to fit in boxes, but realism can’t be considered modern or conceptual. That’s the kind of art I like: pieces that have an idea, have craft. So little attention is given to craft these days.

“The Blast Furnace,” 2018.

Courtesy William Matthews

Which three people, dead or alive, would you like to invite to your next party, and why?

I’ve hung out with a lot of pretty amazing people as it is, but I’d love to have dinner with Benjamin Franklin, whose mind was so agile. He understood the combinations of living in society in a diplomatic way, but was also inventing and actualizing his ideas. That’s a rare thing.

Albert Schweitzer is another obvious example. And Raphael: Part of what interests me is the way artists have utilized their talents over the years. In this time, what I get to do is incredibly self-indulgent. Two hundred years ago, I’d be lucky to work for a church. Raphael came from Urbino, a small town on the east coast of the Adriatic. How does one grow from living in a little village into doing really important work?

Denver (or Colorado), love it or leave it? What keeps you here – or makes you want to leave?

I love living in Denver. I love the size of town Denver is. Great friends and other people come through and visit. To live in New York or Los Angeles, cities that are such vast, bigger pools with more diversity, there’s more going on, but you don’t have time to meet a lot of those people.

I love coming back to this city. I love how it’s a Western city with old and new buildings. I love its history. I grew up in San Francisco and never thought I’d embrace another place, but I’m really proud to live here.

William Matthews was commissioned to create this mural flanked by sculptures at the Dickies Arenea in Fort Worth.

Becky Stevens

Who is your favorite Colorado Creative?

I love the paintings of Quang Ho and the sculptures of Bill Nelson. In the music world, my friend Nick Forster brings so much to this region with eTown. He makes such a huge contribution by bringing people through town so all of us get to hear incredible music.

Daniel Sprick is another amazing painter. Mark Daniel Nelson is a young guy and a great painter – an energetic creative who also teaches. That’s an interesting thing people never talk about in the criticism world: Who’s making a living? It’s a whole different thing to be 57 and doing it most of your life, making all of your money doing artwork. Art has its own set of challenges. To make a living as an artist, you have to be creative about keeping snow tires on the car and cheeseburgers on the table.

That is a whole other interesting story that’s often overlooked. To me that would be a lead story: How have people done it and survived? It’s tricky. It’s hard to do that with integrity and not feel like you’re selling out or doing something irresponsible. We have to be responsible to ourselves and what good work is, and it’s hard to do that and also make a living.

What’s on your agenda in the coming year?

My first child is getting married, so we have a wedding coming up. I have five kids and none are married, so we’re hoping that this starts a domino effect. We’re finishing a house near Evergreen right now. It’s been a huge year for me, getting huge projects wrapped up. Now I’m looking at things with new eyes. It’s an interesting time of life: I’ve been working flat out on a sprint for more than fifty years, and now I’m looking forward to slowing down a little, being more selective about where the energy goes.

If you died tomorrow, what or whom would you come back as?

I don’t know. I’ve lived my life, and I have no regrets. That’s always been my attitude. The implication is that if you came back, you’d do things differently, do things you haven’t done. But I feel like I’ve done all the things I wanted to do. Maybe I’d come back and do some more of it.

William Matthews | Steel runs through February 6 at William Matthews Studio, 2540 Walnut Street. The gallery is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesdays and Thursdays, or by appointment.

Matthews also has work in the 2020 Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale at the National Western Stock Show, open to the public Friday, January 11, through January 26 in the Coors Western Art Gallery, on the third floor of the National Western’s Expo Hall, 4655 Humboldt Street.

Learn more about William Matthews and his work online.