Denver Art Museum

Audio By Carbonatix

“I don’t have kids at all, and I thank God that I never did,” Maurice Sendak, the artist, writer and illustrator most famous for Where the Wild Things Are, once said.

Sendak, then 83 years old, made the admission while discussing his work with NPR’s Terry Gross in 2011, the year before he died. But much like Santa Claus, Sendak didn’t need a kid of his own – he already had overwhelming love from children worldwide. He always responded to their fan mail, and recalled that one letter in particular, with a drawing scribbled on it, caught his eye. In his response, Sendak drew one of his famous Wild Things.

“I wrote, ‘Dear Jim: I loved your card,'” Sendak recalled. “Then I got a letter back from his mother and she said, ‘Jim loved your card so much he ate it.’

“That, to me, was one of the highest compliments I’ve ever received,” Sendak said. “He didn’t care that it was an original Maurice Sendak drawing or anything. He saw it, he loved it, he ate it.”

Where the Wild Things are is Sendak’s most famous book.

Denver Art Museum

You can’t eat the art at the Denver Art Museum‘s retrospective on the illustrator, Wild Things: The Art of Maurice Sendak, which runs through February 17. But just as the smell of a tasty apple pie can immerse you in memories of Grandma’s kitchen, the art covering the DAM’s walls sends a wave of nostalgia over those who grew up reading such books as Where the Wild Things Are, The Nutshell Library, Chicken Soup With Rice and Little Bear.

All of the original pages for Where the Wild Things Are line one of the galleries in this enormous show, and it could be the last time they’ll be seen together: According to Lynn Caponera, executive director of the Maurice Sendak Foundation, they’re still used for reprints. “We go back to the original and use the actual page,” she says. “We used to never allow them to be shown together because we were always worried that something would happen, and we still print from it.”

Where the Wild Things Are has been translated into more than forty languages and printed tens of millions of times, with more to come once the pages return to the Foundation and HarperCollins. But this exhibit isn’t just about that 1963 book, the first children’s story that Sendak both wrote and illustrated. It highlights the entirety of Sendak’s talent, which expanded beyond writing and drawing into opera sets, dioramas, painting, animation and more.

Maurice Sendak

Denver Art Museum

Sendak was born in Brooklyn in 1928 to Polish Jewish immigrants, and his drawings and writing were informed by his upbringing, including the trauma of losing family members in the Holocaust. At the DAM, we see classic self-portraits as well as paintings of his parents and other family members, all faces he would later use in his illustrations – particularly his own. Sendak is recognizable in most of his characters, including the obstinate Pierre (of Pierre: A Cautionary Tale in Five Chapters and a Prologue), Max (from Where the Wild Things Are) and even the baby in Higglety Pigglety Pop! or There Must Be More to Life, which Sendak wrote about (and dedicated to) his dog Jennie.

He was inspired to become an illustrator after watching Disney’s Fantasia. His first commission, at the age of twenty, was creating window displays for FAO Schwarz, where he met Ursula Nordstrom, the editor-in-chief of children’s books at Harper & Row (now HarperCollins). She brought Sendak to that publishing house, where he illustrated for such authors as Ruth Krauss, Crockett Johnson and Randall Jarrell in the 1950s.

A page from Higglety Pigglety Pop!

Denver Art Museum

Several walls in the DAM are dedicated to these commissioned illustrations, which took inspiration from the cross-hatch work of Albrecht Dürer and illustrators from various periods. Sendak’s home studio was often covered by a rotation of whatever work was inspiring him at the moment: reproductions of paintings by Winslow Homer, William Blake, Goya; nineteenth-century children’s books illustrated by Randolph Caldecott, George Cruikshank, Ludwig Richter and Wilhelm Busch.

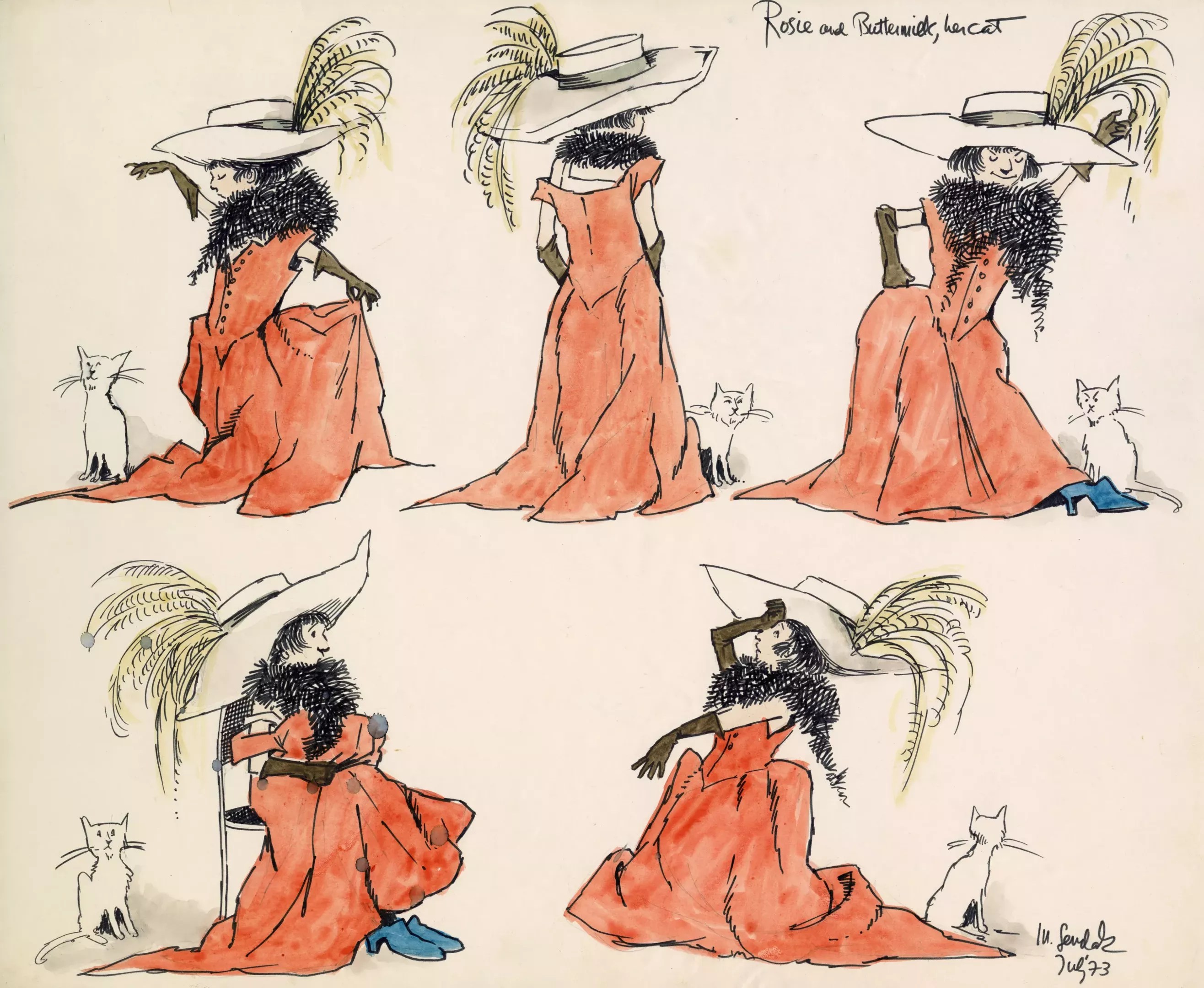

It’s easy to get lost in the intricate details of Sendak’s drawings, but another gem of the show covers the work he did for operas, theaters and ballet companies throughout the ’80s, including a stage adaptation of Where the Wild Things Are. Giant costumes for the Wild Things and other characters are on display, as are dioramas Sendak masterfully designed to influence sets for The Magic Flute, The Nutcracker, The Cunning Little Vixen and more.

A fantasy sketch by Sendak.

Denver Art Museum

He would familiarize himself with the music for such works with his “fantasy sketches,” an exercise he started practicing in the ’50s. These pages show a succession of characters expressing their movements and telling stories in their own right. In a fantasy sketch for a Mozart quartet, an angry toddler is seen crying with his mouth gaping wider and wider until a goose climbs into it. Soon the goose is flying with the child, its feet still in his mouth, until he is dropped into a bipedal fish, which delivers the boy to his mother.

Such energetic motion is echoed throughout all of Sendak’s illustrations, which spring from the page. There is no other children’s book author and illustrator with such a distinct style. As Nordstrom, his editor and publisher, told the New Yorker in 1966: “Maurice is not an artist who just does an occasional book for children because there’s money in it or because he thinks it will give him an easy change of pace. Children’s books are all he does and all he wants to do. His books are full of emotion, of vitality. When one of his lines for a drawing is blown up, you find that it’s not a precise straight line. It’s rough with ridges, because so much emotion has gone into it. Too many of us – and I mean editors along with illustrators and writers of children’s books – are afraid of emotion. We keep forgetting that children are new and we are not. But somehow Maurice has retained a direct line to his own childhood.”

Sendak called Max his “truest creation.”

Denver Art Museum

While that direct line is translated in all of his work, it’s been proliferated through Where the Wild Things Are. Of course, the most fabulous room at the DAM show contains those pages, lush with detailed marks from watercolor pencils and powered with the same liveliness of his fantasy sketches. According to the DAM, Sendak said that the title for his seminal work stemmed from the Yiddish phrase “vilde chaya,” meaning “wild beast,” and the Wild Things are based on his family members, who would pinch his cheeks and make remarks similar to those in the book: “We could eat you up, we love you so!”

It is through these pages that we see why famous New York art critic Brian O’Doherty wrote that Sendak “has given shape to the fantasies of millions of children – an awful responsibility.”

The Denver Art Museum is hosting a retrospective on Maurice Sendak through February 17.

©The Maurice Sendak Foundation, courtesy Denver Art Museum

Perhaps that’s because Sendak had the habit of talking to his inner child each day, or so he told the New Yorker not long after Where the Wild Things Are won the Caldecott Medal as “the most distinguished American picture book for children.”

“You see, I don’t believe, in a way, that the kid I was grew up into me,” Sendak said. “He still exists somewhere, in the most graphic, plastic physical way. … One of my worst fears is losing contact with him.”

Thankfully, he never did. Sendak maintained that inner child through his final work, Bumble-Ardy, which he wrote while his partner of decades, Eugene Glynn, was dying. But of all his characters, Sendak said that Max, the King of the Wild Things, was his “truest creation.”

“Like all kids,” Sendak said, “he believes in a world where a child can skip from fantasy to reality in the conviction that both exist.”

At the Denver Art Museum, you can skip through Sendak’s fantasy with the wild abandon that Max embodies, only to find comfort at home once more. But you’ll soon find yourself yearning for Sendak’s dreamy worlds again.

As a seven-year-old once wrote to Sendak: “How much does it cost to get to where the wild things are? If it is not too expensive my sister and I want to spend the summer there. Please answer soon.”

Wild Things: The Art of Maurice Sendak is on view at the Denver Art Museum, 100 West 14th Avenue Parkway, through February 17. Find more information at denverartmuseum.org.