Desiree Suchy

Audio By Carbonatix

We all hear voices in our heads at times. Maybe it’s a parent, reminding us of something we were taught. Maybe it’s an I-told-you-so from a friend who warned us against something we did anyway. It happened to author and Colorado State University professor EJ Levy, too…only she got a novel out of it.

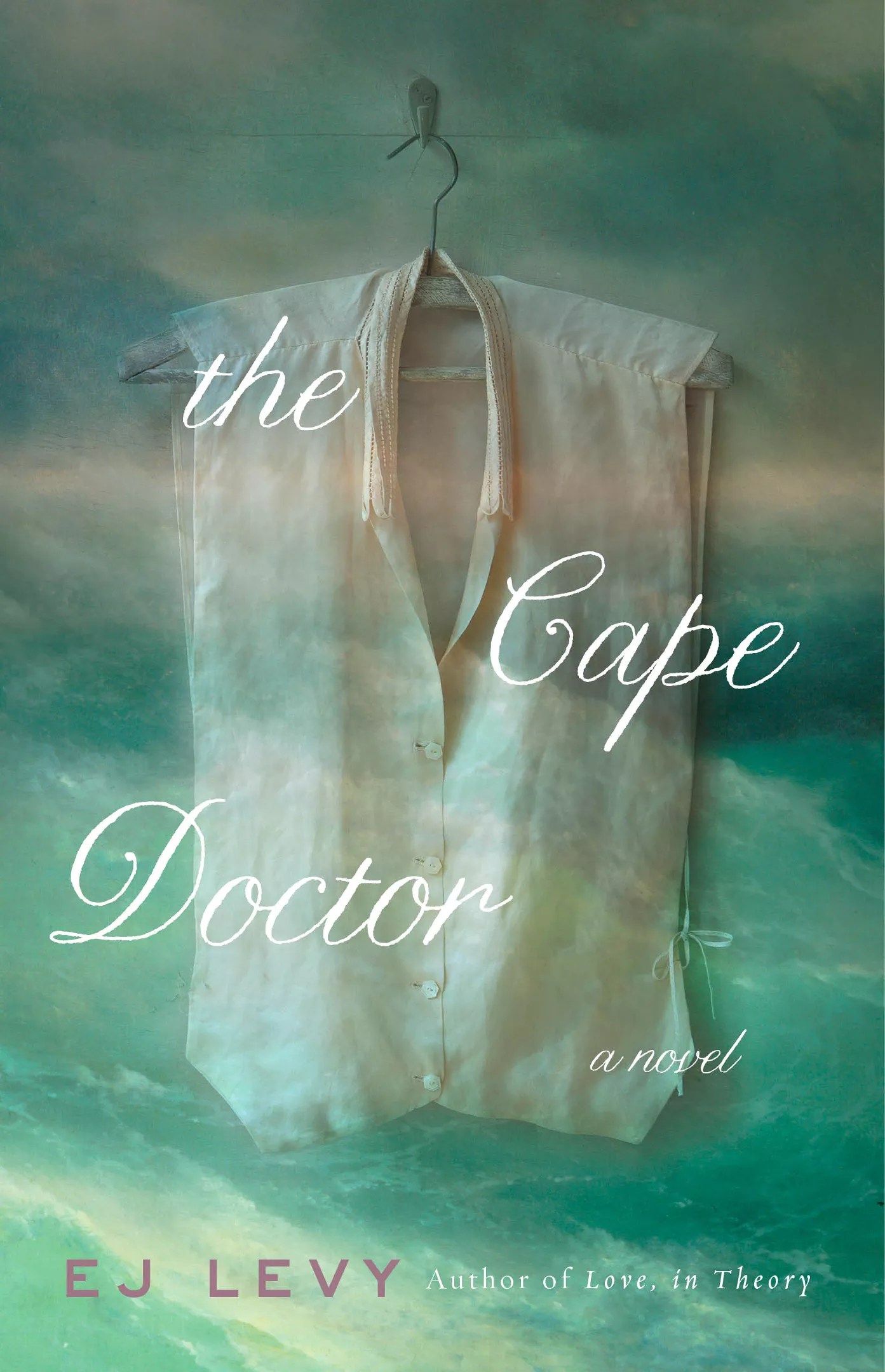

The resulting book, the newly released The Cape Doctor, debuts on shelves this week. Levy will be talking about it and the nineteenth-century physician at the center of it: Dr. James Miranda Barry…who was born Margaret Bulkley. Barry’s career and life’s journey is the focus of Levy’s novel.

We spoke with Levy over email about The Cape Doctor, its subject, and how voices sometimes – when we’re lucky – can lead us in very good directions.

Westword: You’re talking about your book The Cape Doctor in a Tattered Cover livestream on Wednesday, June 16. What do you have in mind for that online event?

EJ Levy: I’m thrilled to have a chance to talk with Adrienne Brodeur about her work and my own. She’s a wonderful memoirist and the executive director of Aspen Words; it’s an honor to talk with her about my debut novel. I hope we’ll have a chance to talk about writing memoir.

My novel is a faux memoir, told by a nineteenth-century army surgeon inspired by the real Dr. James Miranda Barry, who was born Margaret Bulkley circa 1795, so I’m interested in talking about the challenges and charms of writing from fact. In my case, writing about a beloved historical figure about whom some things are known but much is not; in Adrienne’s, writing about a beloved mother who is still very much alive. Each has its own challenges; each is a fraught endeavor, if in different ways.

Little, Brown, & Co

Will your book tour remain virtual, or will you be doing anything in person?

Right now, the tour is exclusively online. We’re holding a limited number of events this month, with stellar writers Adrienne Brodeur and Rebecca Makkai, whose own historically based novel, The Great Believers, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award.

I love that virtual events provide a chance to gather despite distance. I had the opportunity to interview the wonderful actor/director/writer Tom Hanks in April about his short-story collection, Uncommon Type, for a conference in Mexico that drew an audience from around the world. It was such fun, really great! It would have been terrifically complicated had we needed to fly to Mexico or L.A. to chat. And it’s lovely to be able to drink wine at a Zoom reading, which I’ve never been able to do while reading in a bookstore.

So what was it that initially drew you to Barry’s story? How did you first become aware of the historical narrative, and what made you want to tackle it?

In late 2011, while on a flight to Cape Town, I read a few lines about Dr. Barry and was enchanted from the start. It’s hard to explain – sounds odd – but for the first and likely only time in my life, I heard a voice in my head after I read about Barry. As I walked around Cape Town and traveled into the countryside, that voice haunted me: I wondered what Barry would have thought of those places and sights. I found myself taking notes, questions mostly, speculating about what Barry might have made of endemic plants and their possible medicinal uses; what the doctor’s opinion might have been of the Castle, a prison, Tunhuys, the mountains and coast. That voice opens the book: “She dies, so I might live.”

When I returned to the U.S., I began researching Barry and his circle, and medicine and society of the time, and began to write the novel in earnest in 2012. I was enchanted. We know so many things about Dr. Barry and what they accomplished, but really very little of the intimate thoughts of that very interesting person. So I wanted to know those thoughts.

Why do you think you had such an immediate connection like that?

I identified with it. When I first read about Barry, I felt like I got it. After I came out as a lesbian in my mid-twenties, I cut my hair short, defaulted to suit coats and jeans, and was often taken for a man; that was true for about a decade. It didn’t bother me, but it did interest me. I wondered what strangers saw that made them think I was a guy: I think now they saw the confidence that came of dating women. For years I benefited from what I experienced as a kind of male privilege: I was deferred to, flattered, flirted with by straight women and queer. I was assumed to have ideas worth listening to. People actually said, “We expect great things of you” and “All you have to do is prepare yourself for greatness.” I kid you not. This didn’t happen when I was read as female.

And I know a little of the value of a name change: I first began to write under E.J. because my pitches fared better if I was assumed to be male, though the comparison is superficial. Now the name, the mask, has stuck a bit.

How did the book itself develop? Did it change from inception to print?

The writing came easily, but the revision was hard. I had a lot of doubts about my ability to render a time so distant from our own, and I worried about the conventional narrative structure. The book has changed remarkably little from its first draft; more than anything I’ve written, the first draft is the final draft. I did attempt a structural revision in 2015 to 2016, to make the book smarter, less chronological, less nineteenth-century, but it failed miserably. The most substantive change has been the change of major characters’ names, to underscore that this is fiction and not biography. There are excellent biographies: I recommend Rachel Holmes’s book and, most recently, DuPreez and Dronfield’s 2016 book, Dr. James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time, for those who want to know more about the doctor’s extraordinary life.

There’s been some tumult about your use of pronouns both in the book and in talking about it. Can you comment on that a bit?

There was tumult on Twitter after my book’s sale was announced. Twitter is not a place for nuanced conversation, alas. I didn’t know that then.

It seems to me necessary to embrace a certain ambiguity when writing about Dr. Barry. James Miranda Barry (born Margaret Anne Bulkley circa 1795 in Cork, Ireland) was a brilliant, irascible, dandy of an army surgeon, who arguably revolutionized medicine – performing the first successful Caesarean in Africa, finding a treatment for syphilis and gonorrhea, improving the health care of women, native peoples and the enslaved in the Cape colony in the 1810s and 1820s. Napoleon himself called for Dr. Barry on his death bed. Barry was caught in a sodomy scandal with the aristocratic governor of Cape Town in 1824 and later rose to the rank of Inspector General, only to be discovered after death in 1865 to have been “a perfect female,” who had evidently carried a child.

Margaret Bulkley couldn’t have enrolled in Edinburgh University in 1809 to study medicine without assuming the identity of a young man, James Barry; powerful, progressive mentors in London made that new identity possible. When James Barry earned a medical degree in 1812, it was long before any woman known would do so: It would be another 37 years before Elizabeth Blackwell would be recognized as the first woman to earn a medical degree in the U.S. in 1849, and more than fifty years before Elizabeth Garrett Anderson would be the first woman licensed to practice medicine in the United Kingdom in 1865, the year Barry died.

I agree with Barry biographer Jeremy Dronfield, who says, “I have no argument with seeing James Barry as a transgender icon, or Margaret as a feminist role model. I do take issue with those who insist on recognizing one and erasing the other.”

Sadly, this was not the position attributed to me. My novel offers a feminist, gender-fluid interpretation of the life of Margaret Bulkley and James Barry, but I certainly support a trans interpretation of Barry’s life; I think both are valid.

You’ve won much recognition as a writer over the years, but primarily for the short forms. What was it like for you taking on your first novel?

Exhausting? Without my writing group’s support for the first chapters and my ex-girlfriend’s generous cheerleading through years of writerly doubt, I’d not have finished. It’s an endurance test, or it was for me. About two years before I finished the book, I dreamed that I was very pregnant and being urged by the midwife to push, but I refused; I thought I had time. I woke nervous that this dream was about needing to finish the book. Not long after, I dreamed of Dr. Barry yelling at me, raging that I’d not finished the novel. So I got to work, finished it, sent it off to my lovely agent, who sold it to my dream editor. It’s been a journey.

Given your background – the MFA and a Yale degree in History – you seem like the perfect candidate for historical fiction. What are the benefits of that as a genre, as opposed to a more documentarian, non-fiction approach?

Thank you. That’s kind of you to say! When I was studying history, it was fashionable to speak of “intellectual history,” which acknowledges that any historical account reflects the time in which it’s written as much as it describes the past. History is thus a Rorschach: looking back, we see ourselves. But historians nonetheless are obliged to strive for an objective accounting of the historical record, futile as that may be.

But what most interested me about Barry is precisely what the historical record doesn’t record and cannot tell us: How Margaret and James felt about their lives, their choices, their losses, their sex and gender, the child they evidently bore. I wanted to know what isn’t recorded in Barry’s professional papers and James and Margaret’s few letters.

Unlike the historian, the novelist is at liberty to write into the gaps, to write into the silence: fiction offers more liberty; I wanted to let the silence speak. To listen to that voice.

How do you find writing in Colorado? What in the state inspires you?

Colorado is a literary hidden gem; it’s such a wonderful, rich, wide ranging, generous, fierce and intimate literary community. So much inspires me here: You don’t have to drive far to be in wildness, in beauty, to feel small in the scale of things and to feel the weight of geologic time (eons indifferent to us). I think that’s good for writing, that perspective. And I love that when the wind shifts, you smell manure from the feed lots to the east. I like being that aware of the wind’s direction but also conscious of other lives that my comfortable life is predicated on. The beauty of the landscape inspires, of course – the mountains, the dunes, the rivers, the birds – but also the extremes of weather, the precarity of water. One has a keen awareness here of the fragility of our lives as we live them now, a need to be more in balance with all living beings, a kind of daily reckoning that’s important, especially now.

EJ Levy will speak online with Tattered Cover Wednesday, June 16; her book, The Cape Doctor, is available now.