Kyle Harris

Audio By Carbonatix

Gregg Deal has been tussling with punk since he was a kid – even when punks wouldn’t tussle back.

The Colorado-based artist started listening to punk when he was a teenage skater breaking bones in the late ’80s and early ’90s in Park City, Utah. Back then, the largely white, straight-edge crowds at shows weren’t exactly welcoming to an Indigenous kid. He sported the same shirts, went to the same concerts, but never fit in.

These days, when he listens to bands like H20, Rancid and the Interrupters talk about finding their chosen family through punk, Deal shrugs. “I did not have the experience of connecting with people,” he explains. “And I wholeheartedly believe it was because I was too brown. … I hear these stories about the punk scene being so inclusive, and I’m like, man, I missed that – because that is not what my experience was there.”

Deal’s been an outcast among outcasts for as long as he can remember. Growing up in an evangelical home, he often didn’t fit in with his own family. His mother, an Indigenous woman who grew up in an adoptive home, “was in over her head,” he recalls. She was nurturing, but not always able to stand up to his father. And Deal’s father was tough – a white man from the South who treated their relationship like a business transaction. When he was an adult, Deal realized that he and his dad had a lot in common, and they were close when his father died six years ago. Before then, though, the two butted heads.

For Deal, school was terrible.

“There are several instances of teachers treating me poorly because I was brown, either outwardly or subversively,” he says. “But then there were other teachers who were good. … I spent more time drawing and creating than I did doing schoolwork. As a result, my grades were pretty poor. And I was told…as I got older, that I was essentially not smart and that I needed to find a trade, because that’s the route that I was going to be going on. But I never believed that.”

Instead, he kept blasting his music, drawing and dabbling in graffiti, studying whatever he found interesting.

Deal’s father kicked him out when he was seventeen. He moved to Tennessee to live with his uncle. At eighteen, he moved back in with his parents. His father wanted him to complete his GED. He refused.

One night, Deal went to a show with some friends. His buddy had a tattoo gun and inked Deal’s arm. Not long after, his mother noticed the tattoo while they were watching TV, and his dad asked to take a look, too.

“So I take it over to my dad, and he’s like, ‘Let me ask you: Are you just fucking stupid, or do you just not give a shit?’ And me, in my sort of teenage sarcasm, I’m like, ‘I mean, I feel like there’s a third choice in there somewhere.’ And he said, ‘Pack your shit and be out by Friday.’ And so I did. I got everything together and I left.

“He tried to convince me to stay, but under his rules, and I was like, ‘Nah, I’m out. I’m done.’ And he made it very clear when I left: ‘We love you. Come visit. But keep your shit out of the house’ – meaning, ‘Don’t bring your emotions, don’t ask for money, don’t do anything.’ So I knew I was 100 percent on my own.”

Not long after, he moved to Virginia, outside of Washington D.C. After a few years of floundering, he married at 23; at 24 he went to college, where a mentor encouraged him to start studying and making art. He did…but after graduating, he realized that it would be hard to make a living painting in D.C., so he took a job as a designer at a sign shop and worked under a boss who called him various racist names.

“I couldn’t get out of there fast enough,” Deal says.

Looking for an escape plan, he applied for a job at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, which opened on the National Mall in September 2004. That week, Indigenous people flooded D.C., taking over the Mall from the Washington Monument to the Capitol. Deal was disappointed that he had to go to his job at the sign shop and miss the festivities.

“I went to work and he called me Tonto,” he recalls. “And I was like, screw this, man. I’m gonna go.”

He headed out to the opening. Moments later, he got a call on his flip phone: It was the Smithsonian, offering him a position at the new museum.

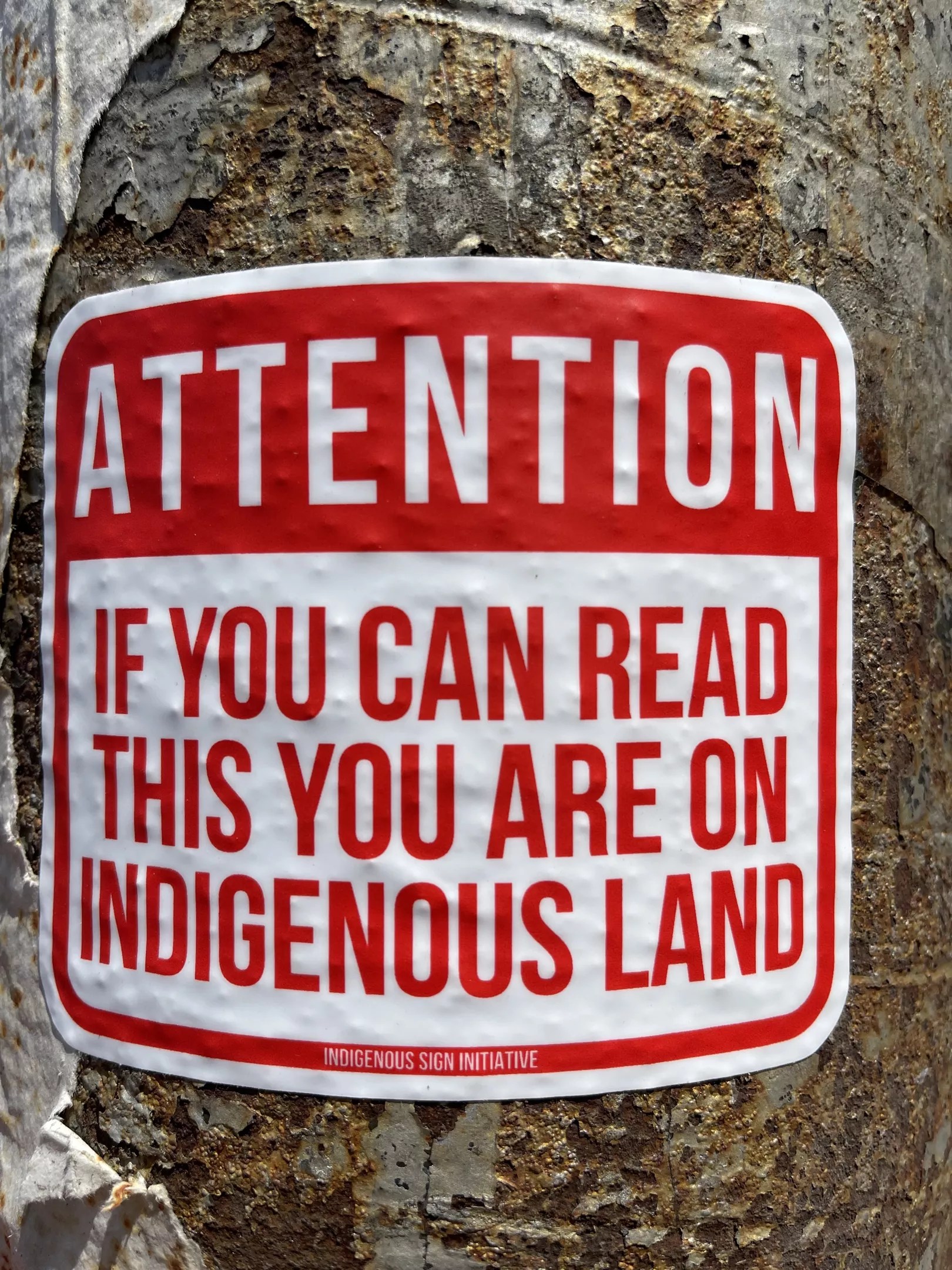

Gregg Deal’s stickers are pasted on street signs throughout Denver.

Kyle Harris

Deal, who is a member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute tribe, worked as a docent with an all-Native staff. The experience was rewarding, though he really wanted to be making art. And soon, he was. The Smithsonian had applied for a Ford Foundation grant to connect a young artist with a mentor. His co-workers tapped Deal, pairing him with performance artist James Luna, whom he’d studied in school.

Back then, “I wasn’t really enamored with the performance end of it,” he remembers. “I was enamored with his voice – that he was just unapologetically Indigenous.”

Luna took Deal to the Venice Biennale. “I was there to assist him for a couple of weeks,” Deal says, “and he ended up pulling me into the performances. And it just opened my eyes, and I came home and basically told my wife, ‘This is not what I’m supposed to be doing. I need to do something else.’ And she supported me.”

Diving into a full-time art career proved tough for the first few years. The economy crashed in ’08, creative jobs were the first to go, and everybody Deal knew started telling him to take a job at a grocery store. With student debt piling up and multiple children to feed, he decided that was a bad idea – he’d never make enough money. Instead, he just created more artwork and hustled. Not that art was lucrative.

By 2013, the couple’s house was going into foreclosure. Deal had created a performance piece called The Last American Indian on Earth, in which he confronted audiences regarding stereotypes of Indigenous people. The project drew an enormous amount of attention: The Huffington Post wrote about him, the Washington Post did a major profile of his work, and Deal appeared on The Daily Show and Totally Biased.

Although he was being treated like an art star, he still didn’t have gallery representation, and money was tight.

The couple managed to sell their house just days before it was set to go into foreclosure. With the equity, they were able to start over. Deal started getting grants and doing larger outdoor murals. He took The Last American Indian on Earth to the National Museum of the Native American and eventually met with John Lukavic, the curator of Native arts at the Denver Art Museum, who brought him out for a residency. In January 2015, Deal and his wife decided to move to Colorado. Shortly after, his father passed away, and he inherited just enough money from a life-insurance policy to make the move.

Although Deal had a high-profile residency at the DAM, the Denver art scene proved challenging to break into. “It felt like when I moved here, it was really tough to make relationships,” Deal says. “It took us several years.”

But now he’s thriving. He’s found support from the Bonfils-Stanton Foundation, RedLine Contemporary Art and the Art Students League of Denver. His murals cover walls throughout the region.

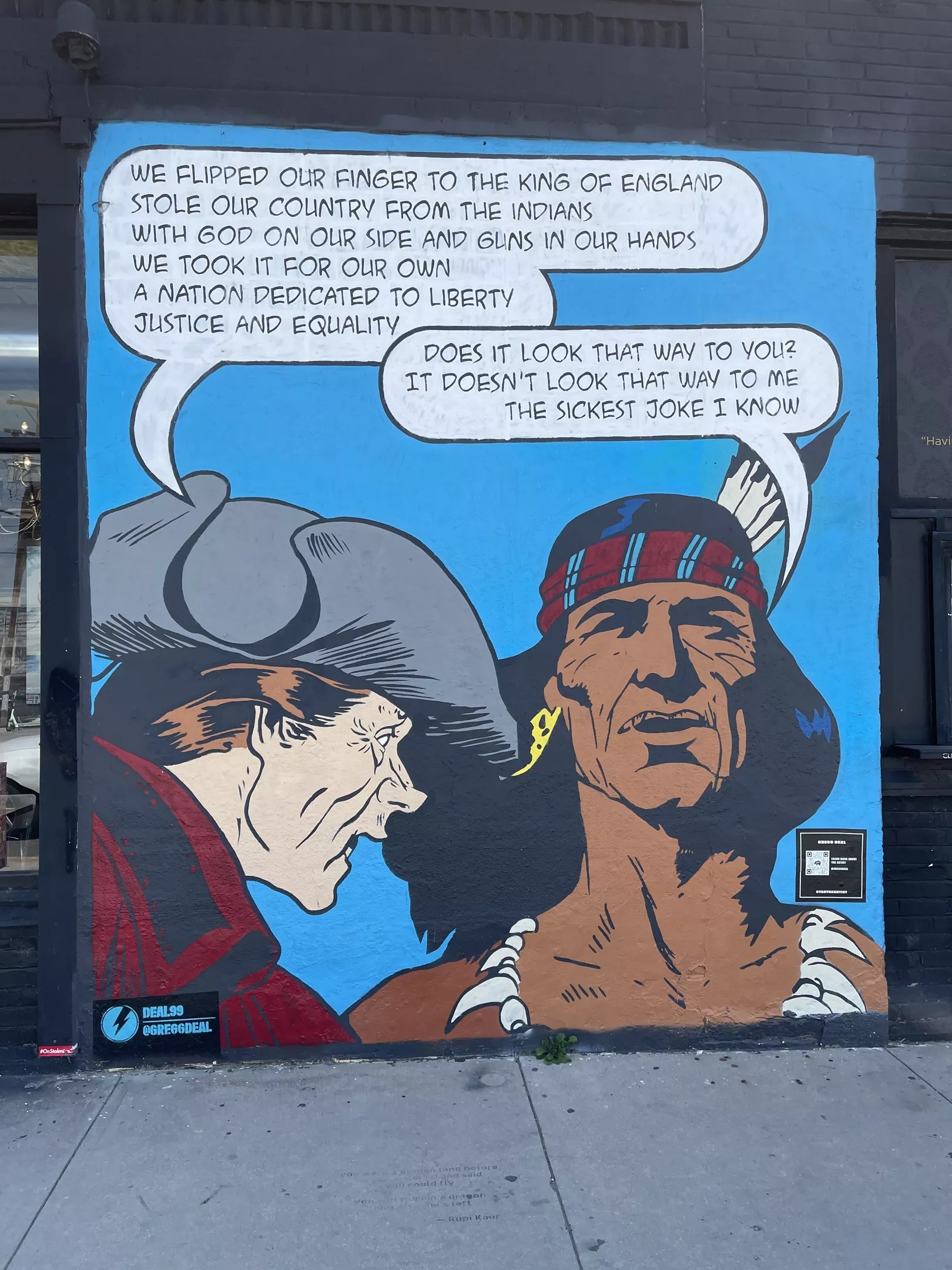

And he’s diving headfirst back into punk, using the music of his youth to take shots at white supremacy and settler colonialism. In a series called The Others, he explains, “I’ve re-appropriated old comic book images from the ’40s and ’50s of Native representation, most of which is steeped in stereotype, [then] redrawn it, repurposed it for my purposes, and I’ve changed the dialogue to lyrics from punk-rock songs. Because I think that the sort of verses of disenfranchisement and equity – it all rings true. Even though they weren’t speaking to me particularly as a Native person, it speaks to me as a Native person.”

In one work in the series – an un-permitted mural painted in an alley during Crush Walls a few years back – Deal depicted a Native person on a horse swinging a hatchet at a Red Coat flinching as though he was about to be hit. Deal used the mural to reflect on gentrification, borrowing a line from the Jello Biafra song “That’s Progress,” in which the Dead Kennedys former frontman sings, “You’re evicted / It’s time to leave / It don’t matter if you’ve been here thirty years.”

Deal painted another mural, without lyrics, of a Native choking a colonialist. Someone painted the words “Racist as fuck” on the Native man’s arm.

“I’m totally fine with that,” Deal muses. “Any work I put in public, I expect that somebody is going to do something to them. I think that’s part of the work. Don’t let me catch you doing it, but, like, I accept that that’s part of the work.”

A Gregg Deal mural outside Crema in the RiNo Art District.

Kyle Harris

Another cartoony image in the series, from 2020, depicts a Revolutionary War Red Coat leaning into a Native man. The white soldier states: “We flipped our finger to the King of England / Stole our country from the Indians / With God on our side and guns in our hands / We took it for our own / A nation dedicated to liberty, justice and equality.” The Native man responds, “Does it look that way to you? / It doesn’t look that way to me / The sickest joke I know.” All were lines borrowed from the Descendants.

“It’s literally lyrics taken out of the song,” Deal explains. “And they’re not even out of context. So I left that there because I felt like that was a good, solid solidarity statement – particularly coming off of Black Lives Matter.”

This fall, Deal will install a massive piece in Trinidad with help from the nomadic museum Black Cube, reinserting Indigenous people into the way the town commemorates the Santa Fe Trail, which has long erased the story of the genocide of Natives. He’s planning two solo shows in 2022 – one of his punk-themed works at RedLine Contemporary, and a simultaneous solo show at the ENT Center for the Arts in Colorado Springs, exhibiting some of his more conceptual paintings.

In recent weeks, he even painted a portrait of his fifteen-year-old daughter, Sage, on the wall of Denver’s Native American Bank, at 201 Broadway. She’s standing alongside two other Indigenous women – the most important in his life, marked with halos around their heads. Sage is sporting an Interrupters shirt, honoring the same band whose logo she wore in another 77-foot portrait that he painted of her in Colorado Springs.

“I’ve been married for 22 years,” Deal says. “Our five kids are all happy, healthy and functioning, and we have a good household. There’s not a lot of toxicity happening there. Both my wife and I are just trying to do the opposite of what we grew up with and trying to do good by that.”

He’s also raising his children on the music that influenced him as a kid.

“Sage is 100 percent punk rock,” says Deal, and his other children are coming along. One of the pleasant surprises about having a punk for a daughter is that she pushes him to experiment and try new things as an artist.

One of those experiments is The Punk Pan-Indian Romantic Comedy, a performance project he tested just before the pandemic shutdown. Now he’s expanding it with a group of musicians from the Music District in Fort Collins.

“It’s about the intersection of Indigenous identity and punk music, which is actually a pretty big thing,” he says.

When he records his voice, he worries that he sounds awful, but Sage encourages him to keep singing.

“It’s one of those things I never did when I was a kid, and I always wish I had,” Deal says. “I think I’m terrible. So it’s…it’s a ton of fun.”

And what’s more punk than that?

For more about Gregg Deal’s work, follow him on Instagram and at his website.