Simon & Schuster

Audio By Carbonatix

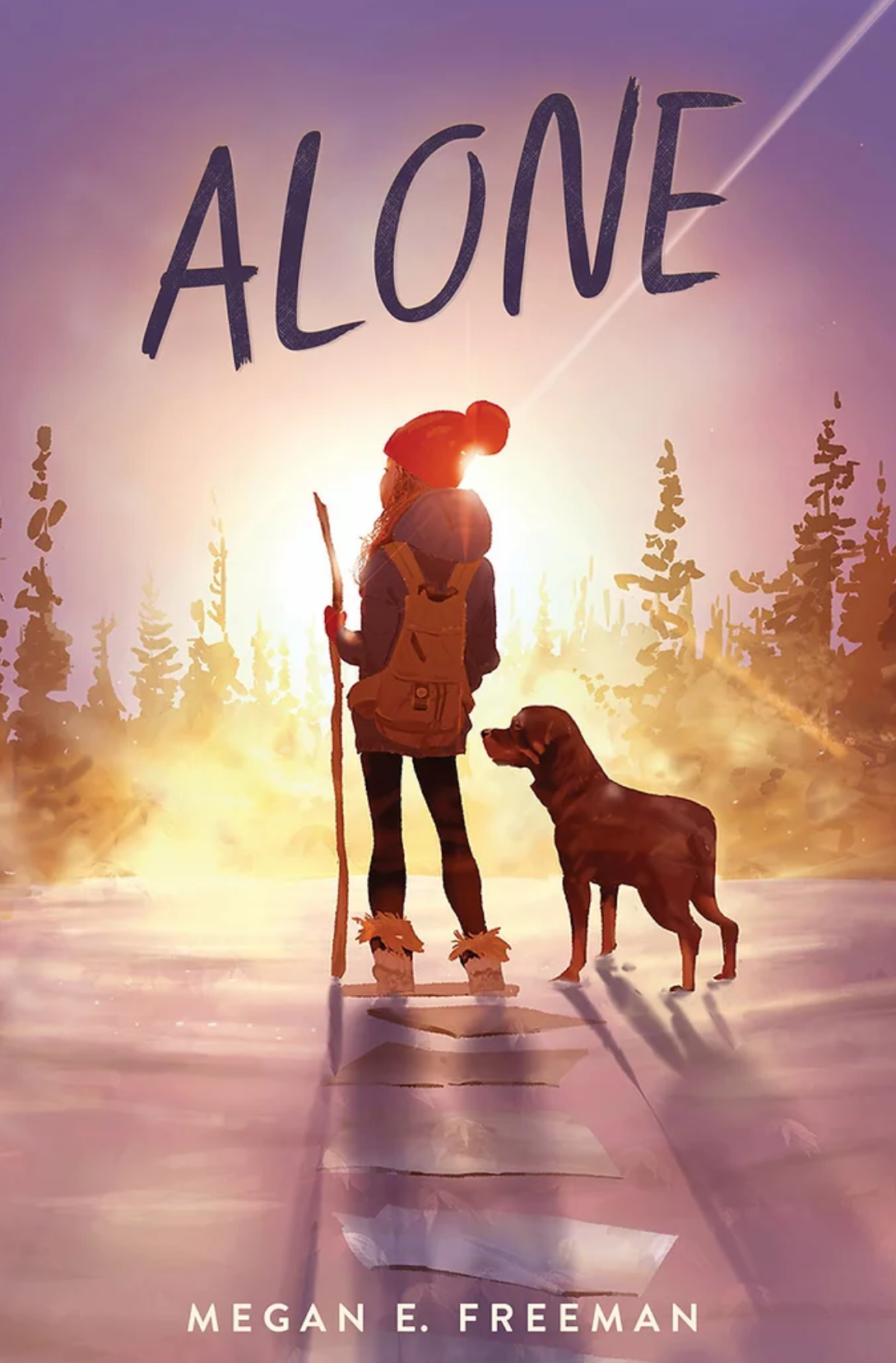

Between pandemics, power failures, climate-change crises and insurrections, doomsday thinking can be pretty hard to avoid, and calculating how to make it through worst-case scenarios has become an all too common hobby. But Berthoud-based author Megan E. Freeman pulls it off in Alone, her thrilling debut middle-grade novel.

The book tells the story of Maddie, a twelve-year-old girl forced to survive after her family has been evacuated from their small Colorado town. With nobody for company but her dog, George, Maddie must figure out how to feed, shelter and protect herself.

Since its 2020 release, the book has drawn a positive response from librarians, schoolteachers and kids alike, who are drawn to Freeman’s snackable writing style. Most chapters are two- to three-page poems, each with concise, to-the-point writing. While a novel in verse might not sound like the most intuitive draw for growing readers, Freeman is hearing that young people are lured in not just by the plot, but by the form, finding it a quick read, while their parents recognize that weighty accomplishment.

“I’ve heard from several parents of reluctant readers – or kids who haven’t dug into reading very much or reading is not pleasant for them,” says Freeman, herself a teacher until 2019. “They’ve really connected, too. I think a lot of that has to do with the novel in verse format. So much white space and so many fewer words to have to decode and get through.”

A novel in verse is also not the most likely format for the kind of survivalist fiction that Colorado’s rugged terrain and libertarian ethos can inspire. What would you do if you were left alone? Could you survive? Would you have the skills? And if not, would you know how to learn them with no internet and no mentors? Hint from Alone: Public libraries would be a smart place to break into if you want to tap into firearms and gardening knowledge, connect to humanity through fiction and poetry (especially that of Mary Oliver), and find a sense of normalcy.

While the book is a fast read, writing it was far from a speedy journey. A decade ago, Freeman found early inspiration in Scott O’Dell’s Island of the Blue Dolphins in a mother-daughter reading group. In that novel, inspired by a true story, a twelve-year-old is abandoned by her tribe on an island off the coast of California, where she raised herself until she was eighteen.

“Little was known about her,” Freeman says. “None of her family or tribe members were alive or there. It was a big mystery. At some point, Scott O’Dell learned about her and decided to write a children’s book that answers some of the questions the story raises.”

Freeman decided to retell that story, only setting it in a small town in contemporary Colorado where the protagonist has access to all the trappings of modern society – at least those that would work after society has fallen apart. Her story’s a literature-loving nail-biter filled with the kind of “what-if” apocalyptic thinking sure to keep your kids – and probably you – up at night.

Megan E. Freeman is the author of Alone.

Laura Carson Photography

As she brainstormed her book, Freeman would drive around Lafayette, where she lived at the time, imagining what a twelve-year-old girl would do if she were abandoned there: Would she break into a store? Would there be enough water? What would happen if she was injured? If she did eventually encounter people from a distance, how would she determine if they were friend or foe?

Freeman wrote her first chapter – then the entire book – in traditional third-person prose. After completing it, workshopping it and sending it to agents who expressed interest but didn’t bite, she decided to rewrite the book in first person and verse.

“Novels in verse were starting to pick up some energy in the publishing world, and I started playing with it and reworking it,” she says. “It opened up so many opportunities I had not been able to find in the prose version. Maddie’s experience is so solitary, and her only interaction is with George. Being able to write the poetry, I was able to get into her experience. It changed from third person to first person. I got into her head. Instead of having clunky sections to let readers know time was passing, I could write a poem about winter and give it a title. I think the quality of the writing was better, as I was a better poet than prose writer.”

She describes the writing process as “building the plane as you fly it.” And after she shifted the structure and tense of her book, it didn’t take her long to find an agent and secure Simon & Schuster as the publisher. Still, the entire process took close to a decade.

“I don’t think I had any illusions that it would be quick,” Freeman recalls, noting that early on, she joined the Rocky Mountain region’s chapter of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. Through the organization, she attended workshops that gave her a good understanding of the rigors of the writing and editorial process and met fellow authors who helped her along the way.

Like many who dropped novels in 2020, Freeman found her dreams of book tours and events upended, but she’s managed to connect with readers through virtual events. Her novel about a girl’s experience of isolation and grief for her missing family couldn’t be more relevant to a generation of middle-grade readers living through a pandemic, stuck at home, schooling remotely and facing an uncertain future.

“When Simon and Schuster bought it in 2019, COVID wasn’t on anyone’s radar,” Freeman says. “It was probably on some scientist’s, but it was not on our radar. And we had no concept of how relevant these themes of social isolation, socialization and loneliness could be.”

For more about Alone, go to Megan E. Freeman’s website.