Scott Laumann

Audio By Carbonatix

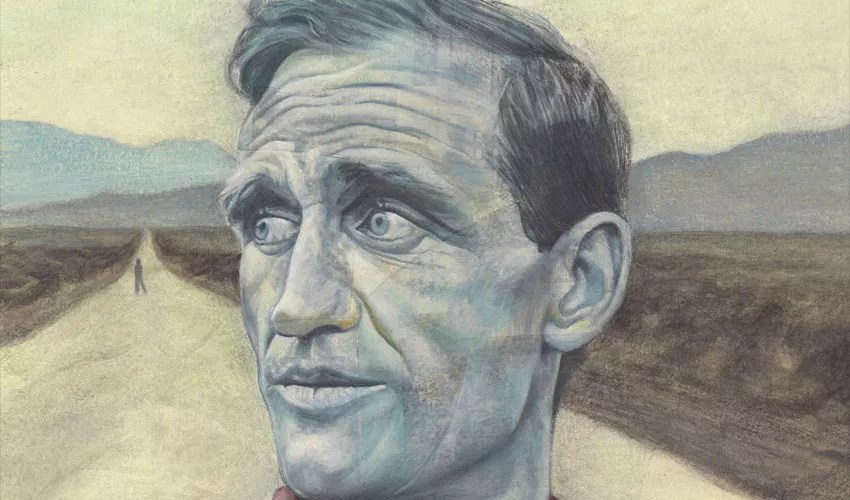

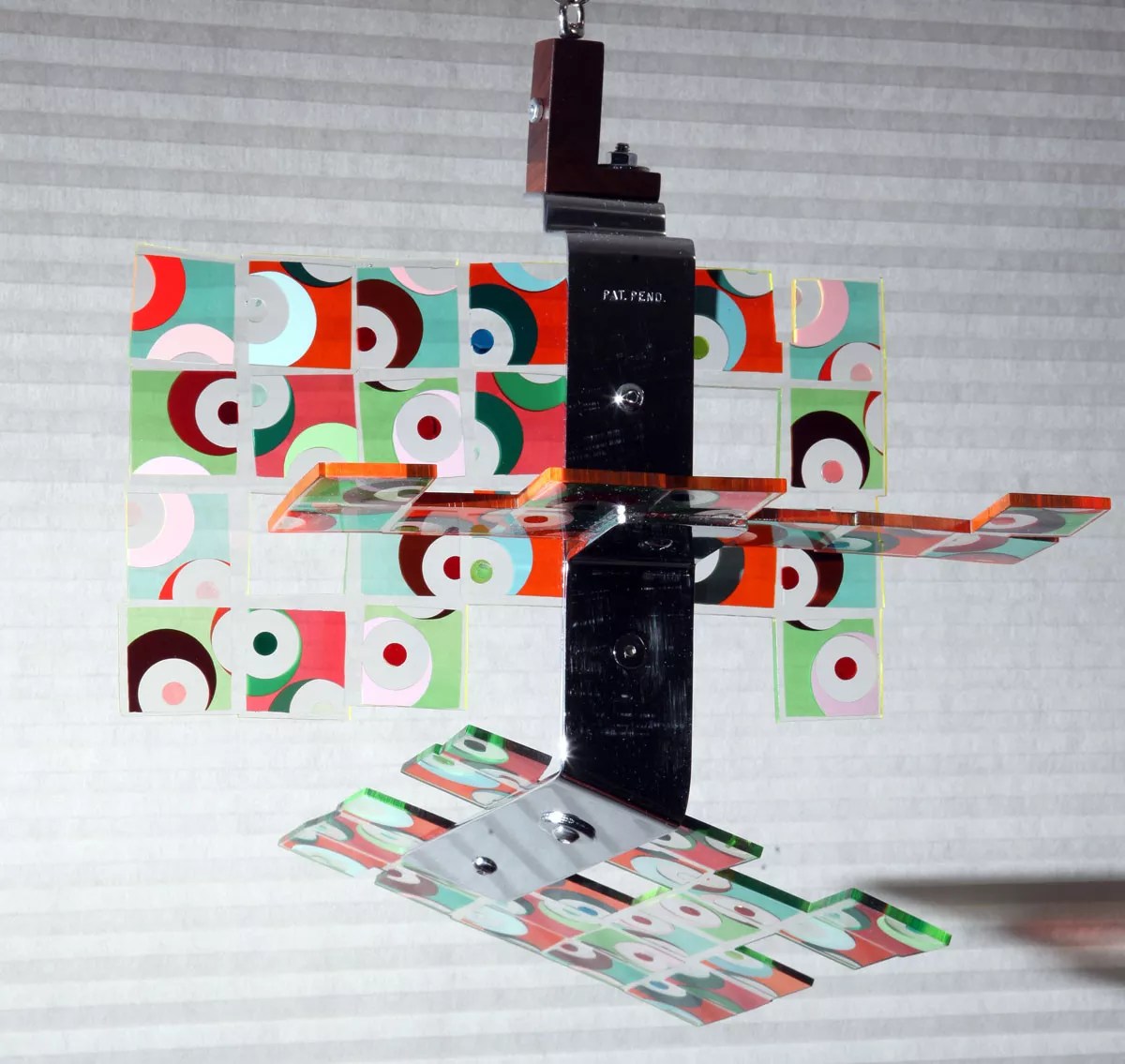

Robert Hyatt calls his latest series of artworks “Combinatorics.” That’s a mathematical term, but he’s adopted it for his own vibrantly patterned visual art.

Hyatt’s “canvas” is a staple at construction sites: oriented strand board, a composite material made of wood chips. He fills in some of the board’s pre-existing chip patterns, maintaining their shape while creating his own designs. He adds links between some of the sections, obscures other pre-existing patterns with color. While the pieces appear to be painted, Hyatt actually uses Pentel and Sharpie pens to provide the psychedelic hues, to create the outlines, and to apply the sometimes painstaking pointillist details.

Hyatt declines to explain his artistic intentions. “It’s up to the viewer to study, as they will, what’s going on within the piece and make their own interpretations,” he says.

Robert Hyatt works on his art.

Anthony Camera

For the past three years, the 71-year-old Hyatt has been steadily at work on his “Combinatorics” – at the same time growing his ponytail down to his shoulder blades, while the hair above continues to thin. A 1971 graduate of the University of Colorado Boulder in fine art, Hyatt had once hoped to make art his primary source of income, but he couldn’t support his family on his earnings. So despite being a self-described “nonconformist,” before his retirement a few years ago, he held a series of responsible jobs, sometimes taking on the role of an administrator after being hired: He’s worked as a counselor for emotionally disturbed children at Colorado Christian Home, taught DUI classes at the Jefferson County Health Department and served as a methadone counselor at Denver Health.

Throughout the years, he created art. Hyatt’s jewelry – earrings, pendants, brooches and stick pins – was included in two Art of Crafts exhibits at the Denver Art Museum in the mid-’80s. The Rocky Mountain News published a photo of Hyatt and his jewelry, calling him a “modern alchemist” for his work with liquid polyresins, which he mixed with colorful dyes and pigments; Hyatt says he was among the first jewelry makers in the country to create designs out of plastics. His work was sold in over a dozen stores and galleries – locally, nationally and abroad. Hyatt also created polyresin panels, some of which now hang beside the stairway at his Arvada condo; they’re a colorful mixture of transparent and opaque elements.

“When you have it just backlit, you see one view,” Hyatt says. “And when you get a front-lit view, it looks like two different pieces, almost.”

Hyatt’s life has contained – and still contains – its own opaque elements.

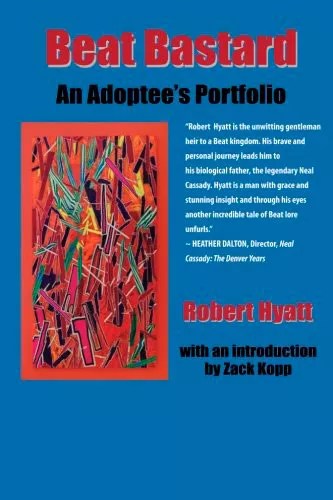

His first “Combinatorics” piece has sold, but he won’t divulge for how much; he’s still considering how to price the rest of the pieces, even though he doesn’t have a gallery lined up quite yet. The image of another piece, “Smart Combinatorics #10,” appears on the cover of his recently published memoir, which details Hyatt’s life from the mid-’40s through the early ’70s in Denver.

It’s called Beat Bastard: An Adoptee’s Portfolio.

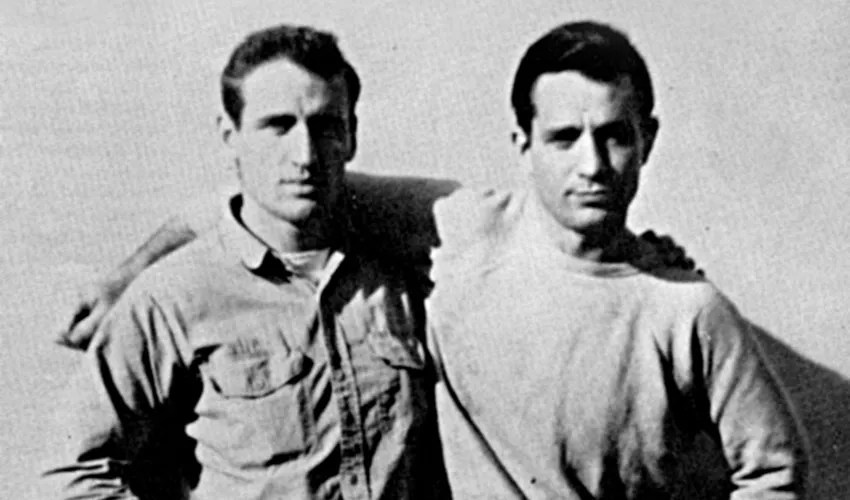

Neal Cassady (left) and Jack Kerouac.

Denver Public Library

In 1945, when Robert Hyatt was born, nineteen-year-old Neal Cassady was incarcerated at the Colorado State Reformatory in Buena Vista. He’d been released from a county jail in California in March 1944, then made his way back to his home town of Denver. But on July 8, 1944, he was arrested for receiving stolen goods from a couple of friends, who’d committed a series of burglaries. Cassady himself had a reputation for car heists; he claimed to have stolen 500 vehicles. Convicted that August, he was sent to the reformatory.

Cassady had grown up in Depression-era Denver, living during one period in a flophouse with his father – a neglectful alcoholic – who was separated from Cassady’s mother, a woman who showed little affection toward young Neal. That history with his father is detailed in Cassady’s own posthumously published book, The First Third.

He attended East High School, but never graduated. He was more interested in stealing cars – and hearts. Cassady not only bedded one teenage Denver girl, but he slept with her mother – and her grandmother – in exchange for a place to stay. He worked as an occasional male hustler as well, collecting cash from men who also desired his body.

In 1946, soon after his release from the reformatory, Cassady married fifteen-year-old Lu Anne Henderson, after spotting her three weeks earlier at the Walgreens on 16th Street. The couple soon made their way to New York City, where Cassady had a friend from Denver at Columbia University. It was there that he met twenty-year-old poet Allen Ginsberg (who has said that he shyly – and gratefully – became sexually intimate with Cassady, at the latter’s invitation) and the boozy, brooding, 24-year-old writer Jack Kerouac. Cassady hoped to one day become a writer himself.

Later that year, Ginsberg and Kerouac traveled separately to Denver to spend time near Cassady. Kerouac’s trip inspired On the Road, recognized as a milestone of post-war American literature after its publication in 1957. The book elevated Cassady – inspiration for the character Dean Moriarty, the fast-talking, quick-witted con man and sexual athlete in Kerouac’s novel – to mythological status. He was “a sideburned hero of the snowy West,” “a western kinsman of the sun.” His car-thief criminality had been an “ode from the Plains, something new, long prophesied.” In On the Road, Kerouac described Cassady/Moriarty as a mixture of both quasi-divinity and irresponsible buffoonery, labeling him the “HOLY GOOF.”

But such notoriety was still a decade away in 1948, when Cassady married Carolyn Robinson, a onetime University of Denver student, after having his previous marriage to Lu Anne annulled.

Around five months later, Carolyn gave birth to their first child, Cathy. But she wasn’t Cassady’s first child. Before his daughter was born, Cassady had written a letter to Kerouac, informing him that Carolyn “is now 7 months along & will present me with my fifth (5) child the last of August. This child, unlike the other 3 boys and a ? – (don’t know) I shall keep, raise, & glory in…”

The four other children had all been born out of wedlock.

Maxine Beverly Beam had an early fling with Cassady.

Courtesy of Robert Hyatt

When Jack Kerouac started writing On the Road, he used the real names of the people he was writing about. Prior to publication, though, the characters were given pseudonyms for legal reasons. Neal Cassady’s Denver-raised friend and road buddy, Al Hinkle, became Ed Dunkel. Rancher Ed Uhl turned into Ed Wall. Kerouac called himself Sal Paradise, Cassady was Dean Moriarty. Cassady’s first wife was dubbed Marylou, his second wife renamed Camille, and his third wife, Diana Hansen, was referred to as Inez.

Maxine Beverly Beam’s name didn’t need to be changed, because she doesn’t appear in On the Road. But her life did intersect with Cassady’s, just prior to the events depicted in the novel.

Interviewed for an oral history about Cassady compiled in the ’90s by Tom Christopher, Uhl had a hazy recollection of one of the women with whom Cassady had been involved: “Yeh, there was a gal he went with from Montrose somewhere, and, uh, I think that maybe she…uh, he fathered her child, at least she claimed that. I don’t remember her name, I remember the gal, she was dark-haired, and he went with her off and on for a period of, like [1945], something like that.”

Maxine Beam was born in Eagle in 1925, but she spent her teenage years in Montrose. A 1940 census indicates that she resided in Montrose with her older sister, her mother and her stepfather. Her mother had remarried a man seventeen years her senior, after Beam’s father had abandoned the family when Maxine was a child.

After graduating from high school in Montrose in 1943, Beam moved to Denver to become a secretary.

In early 1945, she was living at the Florence Crittenton Home on West Colfax Avenue. Pregnant girls from throughout the Rocky Mountain region as well as the Midwest would often be sent there by their families to have babies prior to giving them up for adoption and then returning home. Denver’s facility was one of 75 Florence Crittenton Homes throughout the country dedicated to unwed mothers. “It was a good atmosphere for these young women to be in, even though it was something that they may not necessarily [have been] super-happy about doing,” says Suzanne Banning, who runs the present-day Florence Crittenton Services, which helps unwed teenagers raise their infants while simultaneously completing their schooling. (The Florence Crittenton Home on Colfax closed in 1981.)

On March 19, 1945, Beam delivered a boy at Colorado General Hospital.

After that, she would have been required to appear at a relinquishment hearing in Denver Juvenile Court before presiding judge Philip B. Gilliam. “We’ve had mothers report to our group that, in court, when they were in their relinquishment hearings, he would threaten them with jail time if they ever tried to find their babies,” says Richard Uhrlaub, a historian and boardmember with the group Adoptees in Search.

An adoptee himself, Uhrlaub adds, “A lot of us had great lives – there’s no question about that. But [the adoption] was rooted in a deep, deep loss, and shame and secrecy.”

Robert Hyatt discovered that his father was Neal Cassady.

Anthony Camera

The baby who would become known as Robert Hyatt Jr. was born to an unwed mother in 1945. At two weeks, he was taken from the State Home for Dependent and Neglected Children and presented to his prospective parents, Robert and Caroline Hyatt. The adoption became official on Halloween 1945, and the boy was rechristened Robert William Hyatt Jr. His mother was a housewife, his father a fireman.

Robert W. Hyatt Sr. was, in fact, a second-generation Denver firefighter (his father had commanded a horse-drawn team). About a week after Neal Cassady was arrested in 1944 for receiving the stolen goods that would send him to Buena Vista, Hyatt Sr. was dragging bodies out of a blaze at Elitch Gardens, a notorious fire that Dick Kreck wrote about in Denver in Flames. Interviewed in 1993, Hyatt Sr. described the “controlled madness” of entering a burning building. Like many of the firefighters he spoke with, Kreck recalls the late Hyatt Sr. as being “quiet and soft-spoken.”

Hyatt Jr. idolized his father as a child, reveling in his stories of adventure and danger.

When he was around seven, Hyatt first heard the word “adoption” at school. He came home and asked his mother, “Am I adopted?” She replied that, indeed, he had been – and that’s as far as the discussion went. “I think in retrospect, it was perfect,” he says. “I didn’t focus on it.”

Hyatt’s early years on Elm Court in Denver weren’t exactly idyllic, though. He suffered through a bout of childhood anemia, and then neighborhood bullying. But in his teen years, he would join a gang of boys called the Cherry Poppers, who were always looking for fights.

He was an average student, he says, but never matched others’ speed at learning. When his grades didn’t prove quite up to snuff, he would employ his developing artistic talents to falsify his report card before presenting it to his parents. Later, in college, he would creatively alter Colorado drivers’ licenses for underage friends and paying customers.

Hyatt cites his family’s dynamics as a contributing factor to his unhealthy relationship with alcohol from his teenage years into his twenties. One night in a blackout stupor, seventeen-year-old Hyatt plowed his ’49 Ford into the wall of a dry cleaner, embedding it there. He somehow awoke the next morning in his bed at home, where the police reached him by phone, and summoned him to the scene of the accident. But Hyatt wasn’t charged because of a fluke: The car had been hot-wired and stolen before he bought it, and evidence of that tampering was enough to let him off the hook.

Still, Hyatt’s mother suffered chronic anxiety as a result of the accident. Hyatt remembers her saying more than once, “We might get sued and lose our home.”

When the dry-cleaning business threatened a lawsuit, his father came to Hyatt’s rescue, reaching a settlement with the business’s attorney.

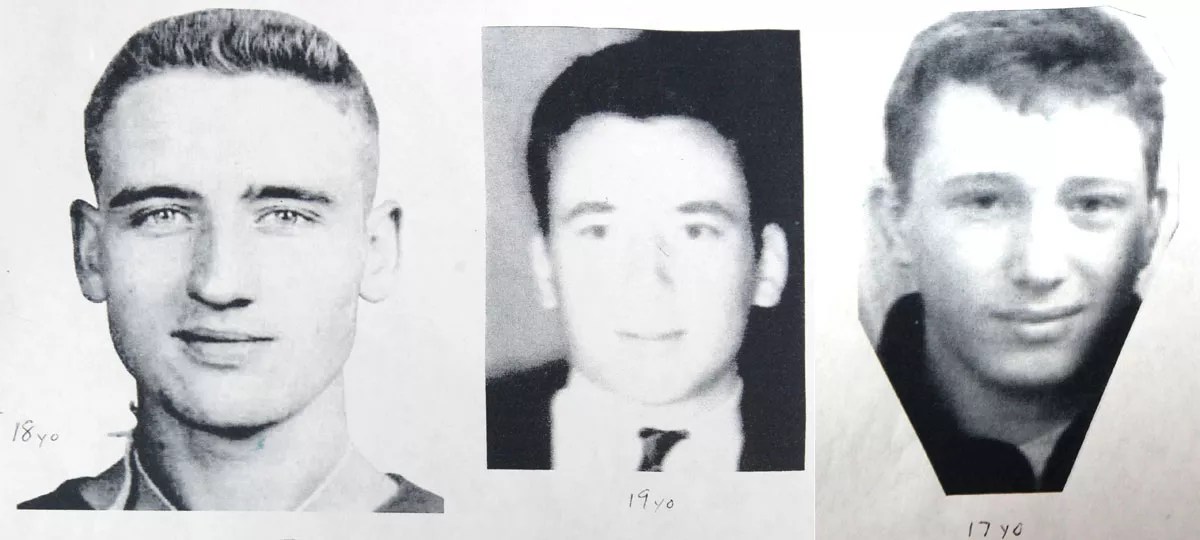

Neal Cassady (from left), Robert Hyatt and Henry Hyatt, Robert

Courtesy of Robert Hyatt

In 1962, the same year that Hyatt crashed into the dry cleaner, Neal Cassady met Ken Kesey – author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – and became part of Kesey’s psychedelic cadre. Cassady had become an underground legend when On the Road was published in 1957, and Kesey and his literary friends were fans of the book. Like Cassady, they were also fans of drugs. Cassady was targeted by narcotics agents in San Francisco in 1958 for dealing marijuana, and he spent time in San Quentin after giving a few joints to undercover police. The bust had ended Cassady’s decade-plus career as a railroad brakeman – and his relatively stable family life with wife Carolyn and his three children. He was free to go on the road.

Tom Wolfe documented Kesey, Cassady and their cohorts, the Merry Pranksters, in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, his new journalism novel. Calling Cassady, with his revved-up facial contortions and spitfire speech, a “monologuist,” Wolfe wrote: “He will answer all questions, although not exactly in that order, because we can’t stop here, next rest area 40 miles, you understand, spinning off memories, metaphors, literary, Oriental, hip allusions, all punctuated by the unlikely expression, ‘you understand-‘”

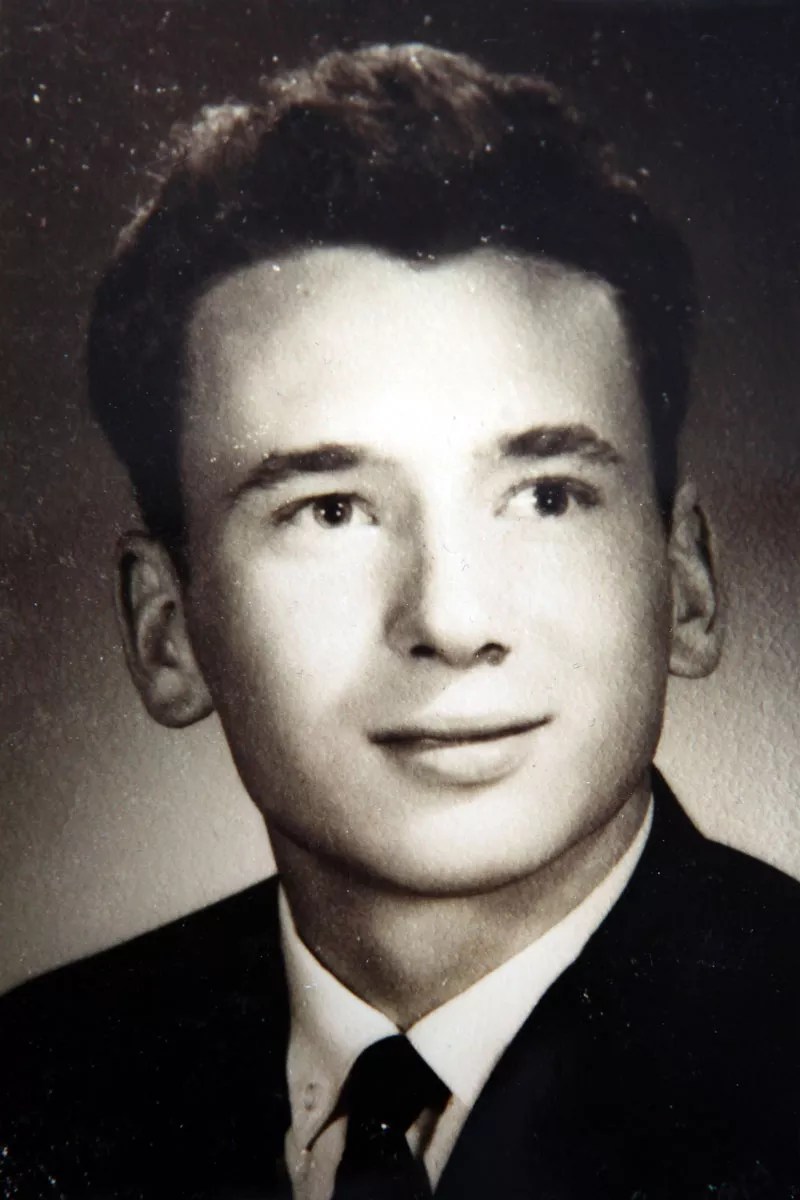

Robert Hyatt as a young man in Denver.

Courtesy of Robert Hyatt

The same year that the Merry Pranksters traveled by bus from California to the World’s Fair in New York, dropping still-legal LSD along the way, nineteen-year-old Robert Hyatt took his own road trip. An argument with his mother concerning his drinking had inspired Hyatt’s anger-filled, hung-over departure to the West Coast in 1964. He nursed his head with drinks offered by drivers who picked him up while he was hitchhiking. He was chased by teenage hoodlums in Fresno. He assaulted a male driver who made a pass at him.

When Hyatt arrived in Los Angeles, practically broke, he couldn’t find the address of the friend he’d set out to visit. He immediately headed back to Denver by bus, his head hanging low. His father greeted his return matter-of-factly: “Well, you’re home.”

Curious about his biological parents, when he turned 21, Hyatt tried to obtain a copy of his birth certificate from the state office responsible for holding birth records. Now legally an adult, he thought he was entitled to the information. That wasn’t the case, though, and after he was brusquely told he could petition the court where his adoption was approved for the release of the information, Hyatt dropped his quest.

The following year, 1967, Neal Cassady – quite possibly propelled by amphetamines – passed through Denver for the last time. He’d been in Mexico, but returned to the U.S. to see his first grandchild in Texas. Then he embarked on yet another cross-country road trip. His face was haggard and made him look much older than he was, but he still had a trim, athletic physique.

But his body gave out the next year. Neal Leon Cassady died in Mexico on February 4, 1968, after passing out by the railroad tracks near San Miguel de Allende. Mexican authorities cited the cause as “generalized congestion” – although drugs had likely played a role. Just four days later, Cassady would have celebrated his 42nd birthday.

Maxine Beam with Hyatt’s half-sister Renee.

Courtesy of Robert Hyatt

Robert Hyatt finally learned that Maxine Beam was his biological mother in 1993 – five years after her death.

Hyatt’s discovery came after a 1989 change in Colorado law. According to a history on adoption-record laws prepared by Uhrlaub, “Colorado became the second state to establish a Confidential Intermediary Program...allowing a party to petition the court for appointment of a trained third party to access adoption records, perform a search for the sought party, and obtain consent for the release of the identifying information.”

By then Hyatt was in his mid-forties. He’d been married (and would be divorced) twice. His short-lived first marriage had resulted in daughter Heather, born the year Neal Cassady died. His second marriage produced three children – Vera, April and Henry – during the ’80s. “There’s reasons to find out medically what your genetics are,” Hyatt says of his decision to petition the court for the appointment of a confidential intermediary.

In late 1993, the intermediary established contact with Beam’s family in Missouri, and they agreed to speak with Hyatt. By early 1994, Hyatt and his half-sisters were exchanging letters and photos.

By then, Robert Hyatt Sr.’s health was declining rapidly; Caroline Hyatt had died three years earlier. Hyatt remembers his adopted father telling him: “Well, son, I’m not going to be around much longer; I’m glad that you have found there’s some family.”

Nancy Danielsen, one of Hyatt’s half-sisters, says that the news that she and her sisters had a brother came as a complete surprise. “We had no clue,” she says. “My mother never said anything.”

“I am sure that it was very hard for her to give him up for adoption.”

But Danielsen remembers that after her mother died from cancer in 1988, she had an eerie sensation that there was some undiscovered secret. She went through her mother’s paperwork looking for clues. After the intermediary contacted her family, she says, “I just thought, ‘That’s it! That’s what I was looking for!'”

Maxine Beam’s older sister Ardith subsequently confirmed to her nieces that Maxine had given birth to a boy in Denver and relinquished him for adoption. Much to Danielsen’s surprise, her aunt then added, “You know, your mother was really wild when she was young.” Maxine’s first husband had no idea of his wife’s past. “He wouldn’t have married her if he’d known,” Danielsen says.

Once they heard from Hyatt, “We were anxious to meet him, and we thought it was cool we had a brother we didn’t know about,” Danielsen says. Hyatt soon arrived for a visit. He and his newfound siblings exchanged stories about their lives, and he learned more about his birth mother.

Maxine had stayed in Denver after the war and gotten married. She’d given birth to two daughters: Sue in 1952, and Nancy in 1954. Divorce soon followed. After remarrying, she gave birth to another girl, Renee, in 1959. Maxine moved with her new husband and family to Dallas, where she worked for the vice president of the company that makes Lee jeans. Since her boss was often traveling, Maxine had a lot of responsibilities – which she relished. But then the family moved again, to Springfield, Missouri, where a job at a bank proved less fulfilling and she chose to be a full-time housewife instead. Maxine was a fairly religious Methodist. And although she never appeared intoxicated, Danielsen says she drank most evenings.

Her mother went out of her way to make people feel comfortable. “She was really pretty outgoing and friendly,” Danielsen recalls. “She was really loving and considerate. She was always nice to people.”

Maxine’s daughters grew up socially conscious and politically engaged. Danielsen, who works in the outreach department of a local library, has raised a son on her own. “It wasn’t such a big deal as when Mom had Bob,” she says. “It was a lot more accepted.”

Still, Danielsen is certain that her mother had regrets. “I am sure that it was very hard for her to give him up for adoption, knowing her,” she says. “I think that was probably a really difficult decision. I think it probably affected her for the rest of her life.”

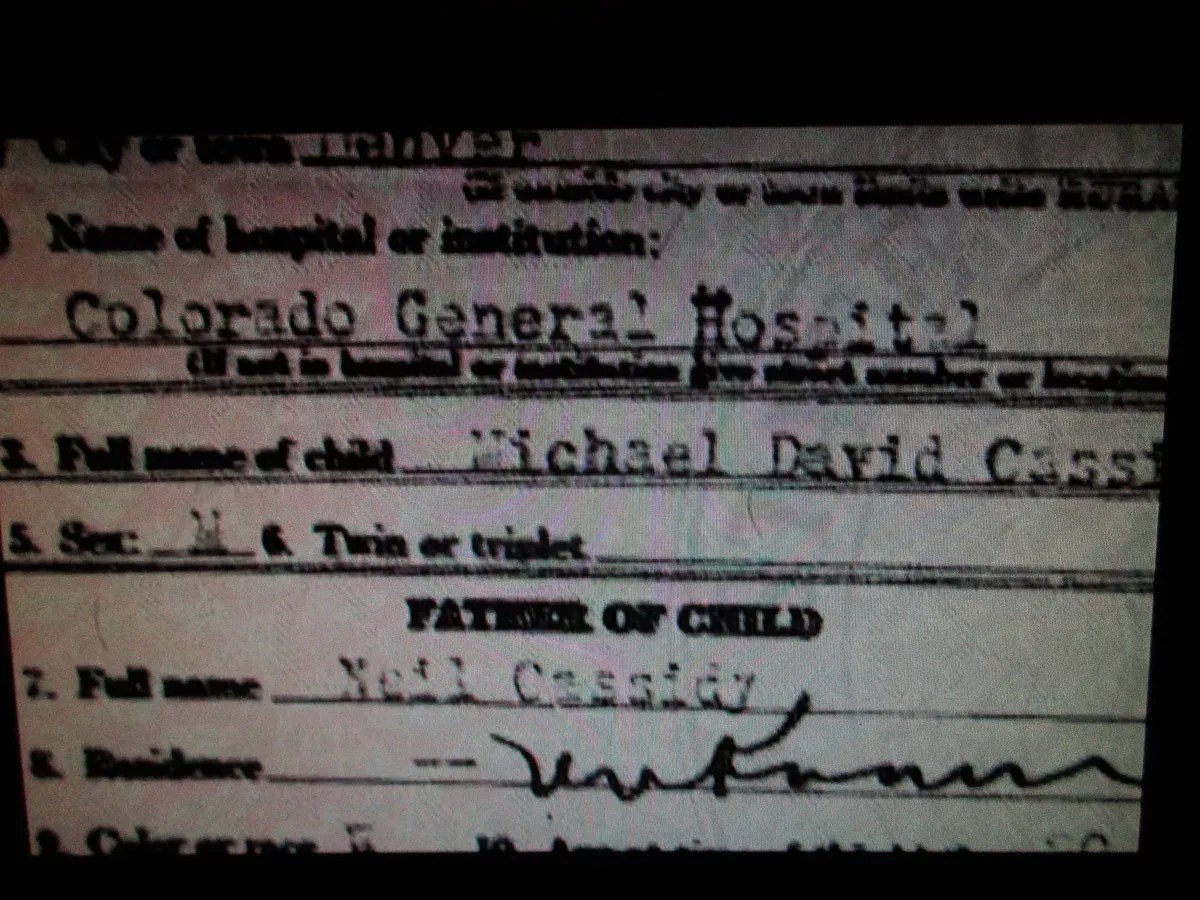

Detail of Robert Hyatt’s birth certificate.

courtesy Heather Dalton

“Can you be discreet?”

That’s what Hyatt says his intermediary asked him in May 1995, when Hyatt’s case before the Denver Juvenile Court – his request to find out more information about his biological father – was being terminated. The intermediary, who was appointed by the now-defunct Colorado Confidential Intermediary Services, had complained to Hyatt that no court in Colorado was as obstructionist as Denver’s.

In fact, in 1992, the presiding judge of the Denver Juvenile Court, Dana Wakefield, had declared the Confidential Intermediary Program unconstitutional; Wakefield was censured the following year by the Colorado Supreme Court for “impermissable exercise of judicial authority.”

Now Hyatt was being denied access to his father’s name by the judge assigned to his case; there was a technicality concerning the birth mother’s ability to contact the birth father, Hyatt recalls.

That’s when Hyatt’s intermediary, who would soon be leaving her position, told him that she’d known the identity of his biological father for over a year – she just hadn’t been allowed to share the details. “His name was Neal Leon Cassady,” she said, “and he died years ago.”

The name meant nothing to Hyatt. Although he’d read On the Road in high school, he hadn’t read any of the biographies about Jack Kerouac or Allen Ginsberg that mention Cassady by name. During the late ’60s, he’d listened to the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, but he wasn’t aware of the man who’d appeared on stage with both of those bands. He’d never read The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

“It makes me sad that he saw himself as a performing circus bear trying to please the public.”

Hyatt, who calls himself “an immigrant to computer technology,” didn’t even conduct a simple Internet search. So the first things he learned about Cassady came through official channels. For instance, he requested Cassady’s original application information from the Social Security Administration – which was forwarded to Hyatt in 1999 by a Freedom of Information Act officer. All Hyatt gleaned from that exchange was that Cassady had applied in 1940, citing his address as 2519 Tremont Street in Denver.

Finally, in March 2011, a friend of Hyatt’s in Ohio suggested they run Neal Cassady’s name through a genealogy website, then do a Google search of “Neal Cassady.” The search results focused on one man in particular.

“That can’t be him,” Hyatt remembers saying. “Scroll further down.”

But then his friend pointed to the timeline – and the references to Denver.

Soon after this discovery, Hyatt hired an attorney, submitted paperwork to the Denver Juvenile Court and was granted “good cause” on June 10, 2011, to access his unredacted, original birth certificate. He subsequently received a copy of his original birth certificate that had been kept in the – aptly named, given his quest – Office of the State Registrar of Vital Statistics.

The birth certificate gives Maxine Beverly Beam’s age as nineteen. Her occupation is noted as secretary at a paper company. Her address is listed as 4901 West Colfax Avenue – the Florence Crittenton Home.

During that era, the names of fathers were often left off of birth certificates, unless they’d consented to be identified. The father’s name here was typed as “Neil Cassidy.” On the lines for his address, place of birth, and occupation, the word “unknown” is hand-printed. His age was given as twenty, although Neal Cassady was actually about seven months younger than Beam and would have been nineteen when his son was born.

Robert W. Hyatt Jr. had begun life as “Michael David Cassidy.”

Artwork by Robert Hyatt

Anthony Camera

During his visit to the Beat Museum in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood in April 2013, Robert Hyatt noticed a painting of Neal Cassady – instead of more famous Beat generation figures Ginsberg or Kerouac or author William S. Burroughs – accompanied by the text, “It All Began With Neal Cassady…”

Hyatt’s half-sister Cathy Cassady Sylvia accompanied him to San Francisco, the site of many Neal Cassady adventures.

Cassady Sylvia first heard about Hyatt from Heather Dalton, a Denver-based documentary filmmaker who was working on a movie about Neal Cassady. After they connected, Hyatt spent a few days with Cassady Sylvia and her husband at their home in Lincoln, California, forty miles northeast of Sacramento. They dined with Cathy’s sister, Jami, and brother John Allen (who was named in honor of Kerouac and Ginsberg). “We’re very happy he’s part of our family,” says Cassady Sylvia. “I just adore him! I’m so happy to have a big brother.”

Cassady Sylvia prefers to recall her father as a devoted family man, not some infamous Acid Test party animal; she doesn’t pay much attention to Beat generation history. “It’s a huge influence on the world, but it’s just not my thing,” she says.

But it’s a big thing at the Beat Museum. “The entire counterculture of post-war America began with Neal Cassady, in my opinion,” says founder Jerry Cimino, who cites Cassady as the primary link between the Beat generation of the ’50s and the hippie generation of the ’60s, which gave rise to a movement that embraced racial equality, women’s ascendence, gay rights, environmentalism and free-form expression.

Introduced to Hyatt by Cassady Sylvia, Cimino blurted, “You guys have the same nose!” Hyatt thinks his ears are similar to Cassady’s, as well. And everyone was floored by how closely a photo of Neal as a teenager resembles Robert’s son Henry around that same age.

“If I had a dollar for every time a guy walks in the door and says, ‘I’m Neal Cassady’s son,’ I could take us both to lunch, honest to God,” says Cimino. “Bob Hyatt is the only guy who ever showed up with a birth certificate.”

“The best I can surmise is they had a one-night or short-term affair, and I was the result,” Hyatt says of his birth parents. He also thinks that his mother wanted to keep him, but the times made it impossible. “I would think she felt very alone, and possibly ashamed, because of the culture.”

On the other hand, Cassady was never ashamed of being a ladies’ man. A New Yorker article described him as a “priapic pinball machine” and a “serial seducer.” He suffered from a kind of “sociosexual A.D.D.,” the article speculated, while describing him as an “uncanny cross between James Dean and W.C. Fields.”

Hyatt learned a lot more about his father during his visit to California. He discovered that Cassady’s 1950 “Joan Anderson letter” to Kerouac – a sterling example of locker-room literature – inspired Kerouac to adopt Cassady’s storytelling style as his own while writing his second novel, On the Road. (Although the original manuscript of On the Road sold for $2.43 million in 2001 to Indianapolis Colts owner Jim Irsay, in 2016 the 16,000-word, single-spaced “Joan Anderson letter” failed to meet the required $400,000 minimum bid at a Christie’s auction.)

Ginsberg wrote about Cassady in his work, too; he was the “secret hero” of the epic 1955 poem “Howl,” one of Ginsberg’s litany of “angelheaded hipsters.”

“Clairvoyants saw a halo around him; many considered him a saint,” said Cassady’s second wife, Carolyn, author of Off the Road, which details her relations with Cassady, Ginsberg and Kerouac.

For innumerable people, Cassady was an avatar of hipness, able to theatrically juggle – through speech and physicality – multiple conversations at the same time. Ginsberg once told the Denver Post, “He was a 1947 precursor of mixed-media, total environment art-form.”

Cassady has been name-checked in song by the Grateful Dead’s Bob Weir and by Tom Waits, Van Morrison and Morrissey. He’s been portrayed by Nick Nolte in the film Heart Beat and by Garrett Hedlund in On the Road. Cassady himself appeared in the Ken Kesey and Merry Pranksters documentary Magic Trip.

“Neal Cassady was like a star that burned brightly for a while, then went out, leaving a trail of loving women and puzzled children and admiring friends,” says fellow Merry Prankster Ken Babbs.

Hyatt jokes that it’s “a dubious distinction to have found out at such a late stage of my life what a character he was.” But despite Cassady’s wayward reputation, he feels protective of his biological father. “If I could have met him a year or two before he died, I would have been mature enough to understand him pretty well,” Hyatt says. “But I don’t know that I would have looked up to him that much at that time, because he was so burned out by then.

“It makes me sad that he saw himself as a performing circus bear trying to please the public, once he got some recognition from the public, instead of his earlier goals of trying to be a writer, wanting to be a good father, a family man, even though, with loose regulations on how to do that, he wanted to do it well.”

Robert Hyatt’s artwork.

Anthony Camera

Hyatt, too, found himself in the public eye: Dalton, who included him in the documentary Neal Cassady: The Denver Years, says, “I think that he definitely was not expecting to have this kind of limelight thrust upon him.”

But Hyatt’s daughter Vera, herself a writer and world traveler, doesn’t think learning of his famous lineage affected Hyatt that much. “I didn’t see that it really changed his outlook on life or how he is or who he is,” she says.

Adds Hyatt’s technically minded, martial-artist son Henry, “I don’t think he likes the idea of sort of riding on Neal’s coattails.”

Both Vera and Henry say that their father was the stricter parent when they were growing up, never wild and crazy.

Still, Hyatt is glad to see his kids display their own nonconformist traits. His daughter April works as a fitness and dance instructor at a spa in Nicaragua. And his firstborn daughter, Heather Hyatt Montoya, worked to bring a treatment for life-threatening infantile scoliosis to America. (Her own daughter, Olivia, who suffered from scoliosis, died at eighteen in 2016.)

Hyatt had started writing his own memoirs long before he found out that Neal Cassady was his father. Now he and his children are included in the book The Denver Beat Scene, by Zack Kopp. Kopp also acted as Hyatt’s literary agent, placing his memoir with Boston’s Big Table Publishing.

Kopp says that Hyatt’s writing style calls to mind that of Charles Bukowski, “basic and plain-spoken – no embellishment.” Hyatt cites Steinbeck as a major influence.

Big Table published Hyatt’s memoir as Beat Bastard: An Adoptee’s Portfolio late last year. “I think we’re going to push it towards the Beat crowd, who are hungry for anything new on the Beat scene,” says Big Table’s Robin Stratton. “But to me, the greatest charm is just the coming-of-age at this real classic, tumultuous time…. People don’t ever get tired of reading about the ’60s and the Vietnam War and the drug culture and free love and those kinds of things.”

Hyatt will read from Beat Bastard at the eighth annual Neal Cassady Birthday Bash, a celebration at the Mercury Cafe on Friday, February 10, in honor of the Denver-raised icon, who still possesses an international reputation five decades after his death.

Music promoter Mark Bliesener has hosted the bashes from the beginning. “I just felt it was really crucial that people in Denver realize that this very important pop-culture figure, very influential literary cat had come out of this city and was very much of this city and the West.”

Some wonder if Cassady’s life is really worth celebrating, pointing to his drug use and sexist behavior. “All that is worthy of discussion – and certainly lots of it is true,” says Bliesener. “But that wasn’t all there was to this guy.”

For Dalton, the most startling discovery was that Cassady “desperately wanted to be a good husband and father…except he wasn’t equipped with the tools to necessarily do a great job,” she says. “And so that, strangely, is the most shocking revelation about him.”

Hyatt has read at the birthday bash before, joining in a lineup that includes poets, musicians and storytellers. This time he will again recite his own text, rather than something by Cassady or Kerouac, because it’s easier for him. He’s intimately familiar with his own material, and that’s important for him, because a lifelong brain condition first diagnosed in the early ’80s has always made reading difficult.

The inspiration for his book’s title came at a previous Neal Cassady bash. Talking to another attendee, Hyatt suddenly quipped, “Yeah, I’m the ‘Beat Bastard’ of Cassady.”

courtesy Robert Hyatt

When Robert Hyatt first began writing his memoirs, he had no aspirations of ever getting them published. After hearing his adopted father’s stories about firefighting, he simply wanted to leave a record for his children of what his early life had been like – and perhaps indicate how his alcoholic behavior had been such a stumbling block.

But he didn’t include everything. Although he wrote about drunkenly ramming his car into the wall of the dry cleaner when he was in high school, he didn’t mention the time in college when he blacked out and plowed his car into a train. In the book, he doesn’t explicitly discuss what had led to his unhealthy relationship with alcohol, but now he suggests, “I was adopted, obviously.”

Despite the heartaches that Hyatt sometimes caused for his parents, just before he died, Robert Hyatt Sr. told his son that he was proud of him.

Although Hyatt’s biological father may be famous, the subject of such books as Neal Cassady: The Fast Life of a Beat Hero, his fireman dad was a true Denver hero.

Hyatt chokes up as he talks about his adoptive parents: “They stood by me through some times that, I think, many people would have said, ‘Geez, that’s my adopted kid. He’s going off the edge here. We’d better just let him go.’ But no, they backed me all the way.”

And now with his book, he’s accomplished his primary goal: pleasing his offspring. He doesn’t have a strong desire to write anything else, preferring to concentrate on his “Combinatorics” artwork.

“I hesitated, at times, about whether I should tell some of the things I did about my behavior and so forth,” he says. “But I decided that the truth is important. And I’ve had nothing but good reactions from my kids afterwards. So I’m glad it turned out that way.”

The eighth annual Neal Cassady Birthday Bash starts at 8 p.m. Friday, February 10, at the Mercury Cafe, 2199 California Street. Get all the details at nealcassadybirthdaybash.com.