Courtesy of Robischon Gallery

Audio By Carbonatix

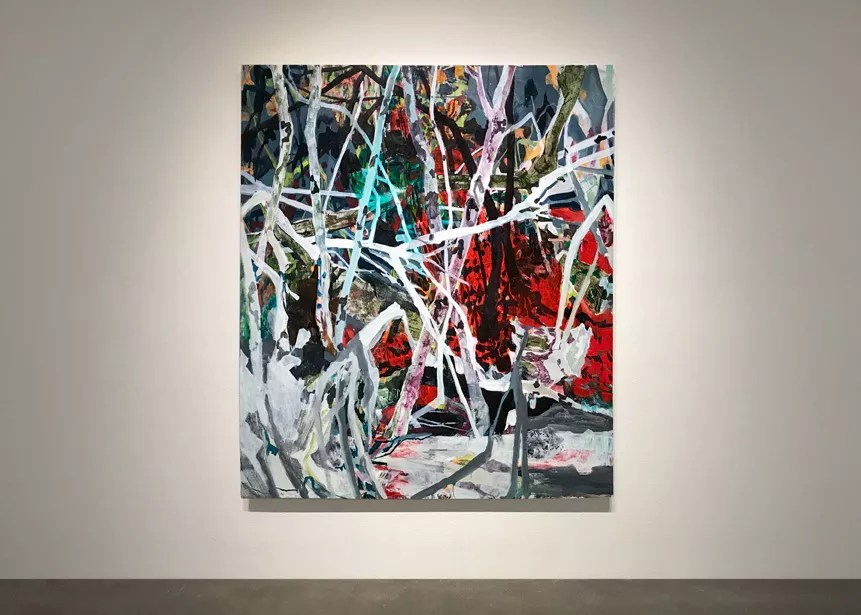

Stepping off the sunny sidewalk and entering the Robischon Gallery on a recent visit was like walking into a shaded forest. The lighting and air-conditioning played their respective roles in making the place darker and cooler, of course, but the impression was sealed by the depictions of trees filling the front space. Those trees are seen in paintings by New York artist Claire Sherman that set a sophisticated tone for Out of View, a wide-ranging group show that also includes photos and videos, all linked by the theme of the natural environment.

The Shermans on view in the front area include a selection made up mostly of small mixed-media works on paper, but three monumental paintings predominate. Two depict bare tree trunks, the third a thicket of branches and leaves. While there’s no mistaking their subjects, Sherman has employed painterly techniques more associated with abstraction than representational painting, including thick, bold strokes. She conveys the illusion of the representations by juggling colors in various complex light-to-dark relationships. Another abstract feature is her handling of the compositions: In the tree paintings, the trunks stand out against a recessive field and have been artfully cropped by the edges of the canvases, while Sherman transforms the thicket into an airy sketch of stains and marks.

David Sharpe, “Waterthread,” pigment print pinhole photograph.

Courtesy of Robischon Gallery

Beyond the Shermans are recent photographic pieces by Denver’s David Sharpe, who works in the realm of pinhole photography, producing images using primitive cameras that he builds himself. Unlike most pinhole photographers, who typically shoot exclusively in black and white, Sharpe works in vivid color. And while his views of the landscape are distorted, he does not abstract them technically. These photos are from the artist’s “Waterthread” series, and all of them depict scenes along Clear Creek as it flows from the mountains, meanders through the suburbs and runs by Denver before ultimately emptying into the South Platte River. The photos are not episodic, arranged geographically or even identified as part of a sequence; Sharpe does not intend to document the creek, but rather to convey its basic nature. For some, the camera is set near the water level; in others, it’s positioned above, taking in the wider view of the surrounding scenery. Certain inevitable characteristics of the pinhole method, such as the curvature of the scenes and the imprecise recording of the details, are exploited by Sharpe to produce dreamlike and poetic evocations of nature.

Detail of “Two Cabins,” by James Benning, two-channel HD video.

Courtesy of Robischon Gallery

The mood changes considerably in the Viewing Room, where Karen Kitchel renders hauntingly dreary scenes of urban incursions on nature. Reinforcing her environmental point, these expertly done paintings have been executed with asphalt emulsion in addition to pigments for colors that range from dingy yellows to grimy browns. Underscoring the idea of an ongoing battle with nature is a video by Isabelle Hayeur, displayed on a monitor, with images of natural scenes and buildings ruined by weather or neglect being overtaken by plants and trees.

Also striking a serious mood is James Benning’s “Two Cabins,” an installation comprising a pair of video projects and two soundtracks. Benning, a pioneer of fine-art video, has long been interested in the interaction of the individual with nature. For “Two Cabins,” he has re-created Thoreau’s cabin in Massachusetts and Ted Kaczynski’s cabin in Montana. Each composition shows a wall with an open window through which the pristine natural environment can be viewed. The two pieces are, for the most part, interchangeable, though when Thoreau looked out his window, he contemplated a transcendental world, and when Kaczynski looked out of his, he contemplated only revenge. Benning’s approach creates moving pictures that are characterized by their stillness; the soundtracks are utterly consistent with the moving images, since the sound recorded is so close to silence.

Nikki Lindt installation of “Reaching Wood” and “Under the Blue,” acrylic on canvas.

Courtesy of Robischon Gallery

The final two phases of Out of View bring us back to the start with abstracted representational paintings. A large selection of Nikki Lindt’s lyrical abstractions, depicting the figure in the landscape, covers the walls of two spaces. Lindt was born in the Netherlands but now lives in Brooklyn. Much of her section is devoted to nearly twenty miniature paintings, almost all of them from her “Dis Place” series, in which a small figure is seen in an ambiguously treacherous circumstance. A woman descends a cliff, a man hangs by a bare vine, and another man enters a dark wood, among other enigmatic situations. Even more impressive are the large-scale paintings based on similar premises. Lindt’s painting is sketchy, even slapdash – but in a good way, with simple, broad strokes splashed on to convey different parts of the picture, which they do quite effectively. Although Lindt works in acrylic, she’s able to get some effects often associated with watercolor, such as transparency; elements of her scenes seem to evaporate. But she doesn’t allow stains to bleed through a translucent layer to achieve this effect, as often happens with watercolors; instead, she renders it directly. This engaging detail is clearly seen in “Under the Blue,” in which the main trunk of a tree that a woman is sitting in disappears in places as it rises toward the sky.

Allison Gildersleeve, “A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,” oil on canvas.

Courtesy of Robischon Gallery

The last of the artists, Allison Gildersleeve, also balances abstraction with representation, but her style leans close to abstract-expressionist. This is partly the result of her painterly moves, like applying thick smears of paint that are allowed to run, a method associated with abstract painting. She also pointedly paints out lower levels, making no effort to disguise the evidence of such an alteration – something else taken from the toolbox of abstract painting. Her tilt toward abstraction shows in her densely conceived compositions, as well, with lines and shapes overlapping one another in crowded masses. In a work such as “Overhang,” the idea of a twig hanging down is readily perceivable, yet when you look closely, the picture is built from colored scribbles and daubs surrounding some crudely painted linear elements standing in for twigs. Gildersleeve pushes abstraction even further in paintings like “Squall” and “A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing” – so much so that they could almost be called landscape-based abstracts instead of the abstracted landscapes they actually are.

The way the work of the artists in Out of View has been stitched together through their different if interrelated aesthetic concepts and media indicates that the show was very thoughtfully curated. Once again, Jennifer Doran and Jim Robischon, the gallery’s owners, have put on an exhibit that rivals those at top museums in the area.

Out of View, through July 8, Robischon Gallery, 1740 Wazee Street, 303-298-7788, robischongallery.com.