James Florio, Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

Audio By Carbonatix

The term “midcentury modern,” which is a very popular brand right now, has taken on a catch-all quality, with a wide range of disparate styles shoehorned into the same category. I’ve even seen it used to describe 21st-century creations, despite the fact that it clearly refers to the middle of the 20th century. On one end of a true midcentury sensibility is elegant naturalism; on the other is chic industrialism, with innumerable permutations somewhere in between – and beyond – these two. Even when the art, architecture and design of the 1950s to the 1970s was brand-new, the sensibilities that inspired things like abstract expressionism, Usonian architecture, functionalist design and on and on seemed to represent a significant cultural moment in American history. In one field after another, the United States had supplanted Europe, devastated by the war, as the world’s aesthetic leader. In this country, newly affluent citizens, weary from the dreariness of a decade of the Depression followed by the war years, readily embraced modernism.

A selection of clocks by Irving Harper for George Nelson Associates in Serious Play.

Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

Over the past quarter-century, libraries of research have been created on modernism’s origins and articulations, so it might seem like there’s little to be explored. But Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America, now at the Denver Art Museum, really does offer a fresh take on the furniture and decorative art of that time by focusing on whimsy as a motif that links otherwise unconnected conceptual currents, just as the title implies.

When I think of fun things dating from that period, I usually think of kitsch, which is generally seen as representing campy bad taste, like Howdy Doody lunch boxes or those wall clocks in the shape of cats that have swinging tails standing in for their pendulums. But that’s not what the co-curators of Serious Play – Monica Obniski from the Milwaukee Art Museum and the DAM’s Darrin Alfred – had in mind. This may be the first time that a museum show has been devoted to exploring the role of play in midcentury design, Alfred says, making it by implication an overlooked component of the movement. In a way, though, the fact that play has a role in serious design is no more surprising than the role it has in kitsch: This was the baby-boom era, after all.

Obniski and Alfred succinctly lay out their intentions in the opening vignette, which includes a group of fairly famous midcentury works, arranged to underscore their lyricism and to de-emphasize their high-art connections to abstraction and surrealism. On one stage-like riser are the “Coconut Chair” and the “Marshmallow Sofa,” both by George Nelson Associates, which display geometric shapes; on another, Harry Bertoia‘s “Bird Chair and Ottoman” sits next to a “Womb Chair” by Eero Saarinen, both with organic shapes. The bold, sculptural characteristics of all of these pieces radically redefine the standard shapes of chairs, sofas and ottomans. These works are supplemented by samples of printed fabrics done by an artist who’s just being rediscovered, Ruth Adler Schnee, one of only three designers in Serious Play who are still living.

Furniture classics by Charles and Ray Eames, including a “Sofa Compact” upholstered in Alexander Girard’s “Colorado Plaid” fabric.

Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

During this period, artists applied the idea of play to upend expectations for how things were supposed to look in every category imaginable, including wall clocks. This show includes a great selection of Irving Harper’s outlandish responses for George Nelson Associates, along with some preliminary drawings for a few of them. Many have scientific pretensions in their shapes and look like atomic-age symbols; others simply exploit the properties of the materials from which they are made – notably plywood, brass and ceramics.

Modernist icons Charles and Ray Eames are clearly the guiding lights of Serious Play, even though they don’t make an appearance until a third of the way through the show, with a setting that includes a “Sofa Compact” covered in the famous “Colorado Plaid” fabric designed by Alexander Girard and specially made for Colorado State University. Other master works by the Eameses displayed here include a “Surfboard Coffee Table” and a “Cat’s Cradle Chair,” along with an “Eames Storage Unit” and other objects. It’s almost as if the curators see the Eameses as exemplifying the era while wearing Girard-colored glasses. All three were not only designers, but lifestyle gurus: The new families starting up after the war needed to furnish their homes, and these designers knew how they should do it. Their lifestyle influence extended way beyond simply touting their own products; they also suggested a range of decorative artifacts to be used with them, including tribal art and folk art in forms from ceramics to weavings. So instead of complementing the furniture with modernist accessories, such as studio pottery, that might be expected during this time period, the curators put kachinas on the storage unit and hung butterfly kites over the sofa.

Whimsical decor and furniture by various designers, including a weather vane by George Nelson Associates.

Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

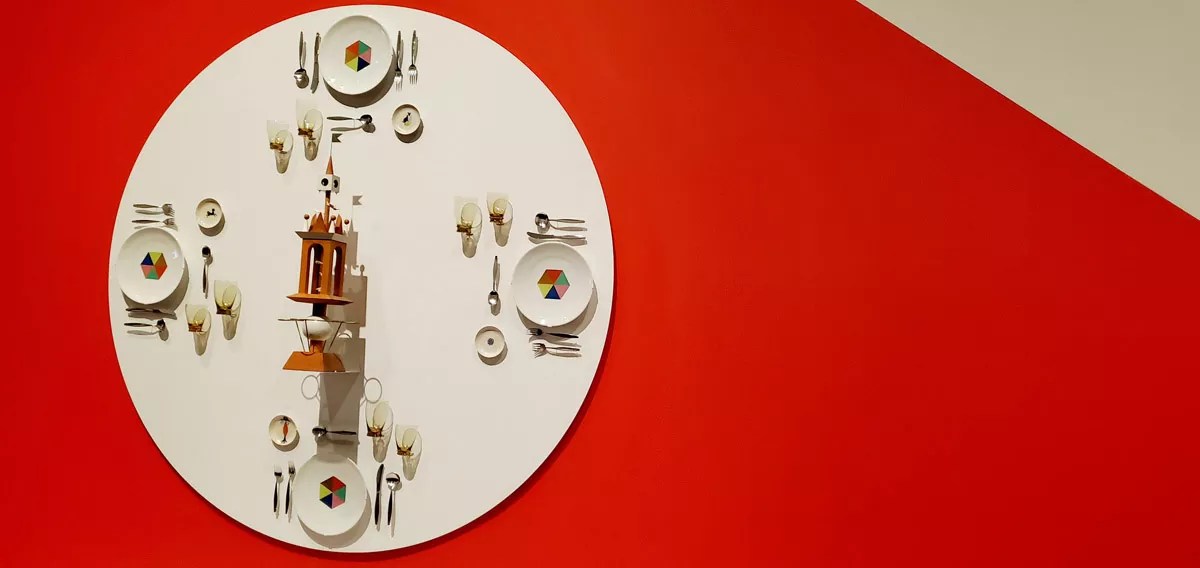

Additional sections devoted to the Eameses show their decks of cards and their films of spinning tops, a toy parade and a perpetual-motion whirlygig. Girard is also represented by folkloric items – dolls, pillows, knickknacks – that he selected to be sold by Herman Miller, the company that made his and the Eameses’ furniture. A Girard table setting has been strikingly mounted on the wall vertically, making an unforgettable moment.

Serious Play includes toys and children’s furniture by other designers, both famous and much more obscure. The “Swing-Line” children’s furniture by Henry P. Glass falls into that second category. His modest cabinets and tables in simple, unadorned shapes are carried out in a variety of bright colors, suggesting both the circus and Mondrian.

While the show’s main thrust looks at domestic life, it extends to the business world, as well. Today corporations are not particularly associated with high style, but things were different sixty-plus years ago, and corporate acceptance of modernism, which Girard championed, was widespread. Back then, businesses felt that the way to prove to customers and clients that they were up to date was to show it. The most obvious example is advertising – in particular, campaigns designed by Paul Rand, including some wonderful poster ads he did for El Producto cigars.

A table setting designed by Alexander Girard, mounted vertically on the wall for Serious Play.

Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum

Among the rarest items in Serious Play are several one-off objects created for Alcoa, which were intended to explore new uses for aluminum. Sadly, most of the pieces from this program have been lost in the intervening decades, but the curators were able to locate a handful of examples along with some photos. For example, they included the model for a screen by Colorado’s Herbert Bayer, the full-sized version of which was actually built (unlike a lot of the original concepts) and still exists in Aspen.

The final part of the show includes reproductions or re-creations with which people can interact. The most interesting is Isamu Noguchi’s stripped-down version of monkey bars that’s meant to be climbed on. (The model for this was made in the 1960s, before people began bizarrely climbing on actual sculptures.)

Serious Play holds up through repeated visits, not just because it includes some of the best designs of the 20th century, but because so many of them still check all the right boxes in the 21st.

Serious Play, through August 25, the Denver Art Museum, 100 West 14th Avenue Parkway, 720-913-0131, denverartmuseum.org.