Cristina Bejan

Audio By Carbonatix

Lady Godiva rides again – or at least she’s waxing poetic and winning honors. Metropolitan State University history professor Cristina A. Bejan goes by the name Lady Godiva when she’s performing her spoken-word poetry, mostly about the crimes of communist totalitarian Romania, mental health and sexual assault. And her recent collection, Green Horses on the Walls (available now through Finishing Line Press), has been named by the Independent Book Publishing Professionals Group as one of the best indie books of 2021.

Bejan’s debut book of poetry is a finalist in the Women’s Issues category in the 2021 Next Generation Indie Book Awards, the world’s largest book-awards program for independent publishers and self-published authors. The winners and finalists will be honored June 25 in an online event that will stream live on Facebook at 5 p.m.

We spoke with Bejan about her life, her work, and about how poetry shaped her – and how she’s in turn using it to shape the world for the better.

Westword: You’ve recently been honored by the Indie Book Awards for your collection Green Horses on the Walls. Can you talk a little about that book and how it came about?

Cristina Bejan: Green Horses on the Walls is comprised of the spoken-word poems I have written over the past ten years. I never set out to become a spoken-word poet, though I have been writing poetry ever since I can remember. My first poems were in German, because I felt it was my secret language. My parents didn’t know German, so if they tried to read my journals, they couldn’t understand what I wrote. In 2010, I was a lonely post-doc in Washington D.C., and I rode my bike one Wednesday evening to read something I had scribbled down at an open mic at the nearest Busboys & Poets. I never looked back.

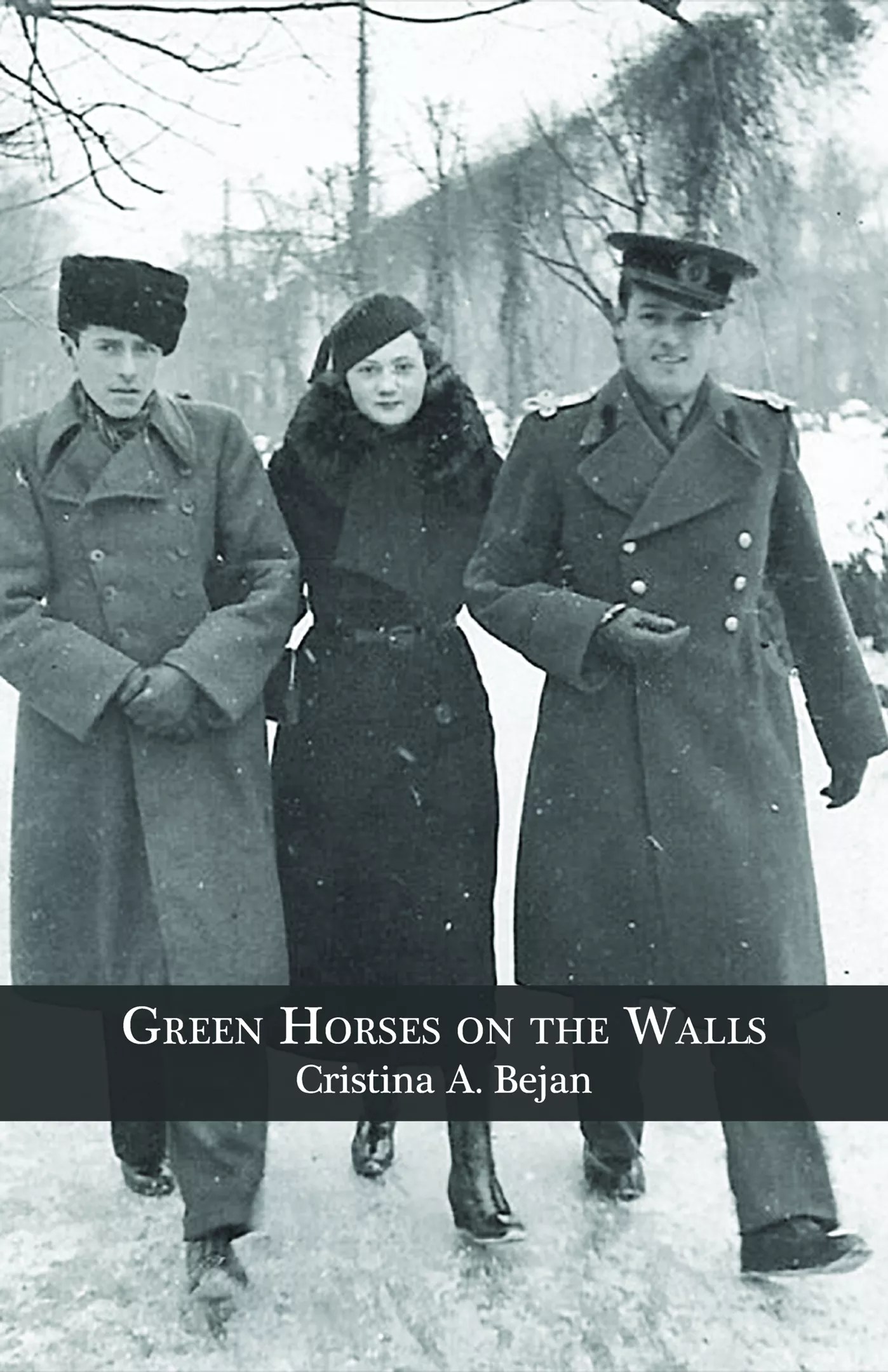

The cover of the collection depicts Bejan

Finishing Line Press

How did you come up with the pen name Lady Godiva?

The name naturally came to me. The chair of my Rhodes Scholarship selection committee, the late New York Times columnist Johnny Apple, called me “Lady Godiva” when I was selected for the scholarship in 2003. I had not heard of her at that time, but when I looked her up – learning that she had fearlessly defied her husband and rode naked through the town to protest tax exploitation – I promised myself that through my art, I would fight for justice, just as Lady Godiva had done.

I became a regular at Busboys & Poets, and one night at their 14th and V location, a poet came up to me and invited me to an underground mic. He was scouting poets, essentially. His name is Orville “The Poet” Walker, and he is the host of Pure Poetry, a monthly open mic in Washington D.C. It was by attending Pure every month that the poems in this book really came together. I felt so free and at peace at those open mics. I look at those years with such fondness, sharing the stage with Lee Davinci, Kenny Sway and, of course, Orville himself. At some point, a friend took me to the other side of Howard, up a couple flights of stairs, to perform at my first Spit Dat. I had not seen, and still have not seen, anything like Spit Dat. Standing room only, energy out the roof. And so welcoming and supportive.

And you’ve kept up the open-mic work since moving to Denver?

At as many open mics as possible: Creative Strategies for Change, Sacred Voices, Tattered Cover and Mercury Cafe. I feel like I was just getting started when the pandemic hit. Luckily, I was able to participate in CSC’s monthly Community Cypher open mics on Zoom, hosted by creative force Bianca Mikahn. It was such a gift to be spontaneously invited to have the Denver launch of Green Horses on the Walls last summer at CSC’s August 2020 Community Cypher.

My poems are mostly about the crimes of communist Romania, love, mental health, and sexual assault. I always caution people that the poems deal with difficult topics. These poems are written mostly in English with Romanian and French making special appearances. For me, sometimes things are better said in another language, or I feel a particular line in Romanian rather than English. In terms of the French, the conversation depicted in the poem “Moral Force of Character” took place in French, so that language choice was obvious.

How did publishing the poems as a collection come about?

I finally got the courage and the curiosity to try. I was publishing my history book, Intellectuals and Fascism in Interwar Romania: The Criterion Association, and thought, “Well, I have all these poems…maybe I should try to publish them?” Finishing Line Press was gracious to pick them up, and the rest is history. My next challenge is to publish my eighteen plays. But one thing at a time.

It’s spoken-word poetry. How does that translate to the printed page? Are there benefits to the physical form as opposed to the performative?

The benefits to having spoken-word poetry in print is accessibility and reaching a broader audience. Green Horses on the Walls is available on Amazon and all online sellers. I have been overwhelmed by the positive response I have gotten from people all over the country posting photos of themselves with a copy of my book on social media. I am in disbelief that the book has so many – yes, very positive – Amazon reviews! It has also been reviewed internationally. And I am currently working with a translator in Romania to get it published in translation by a Romanian press. I am also very aware that my book found a natural home in the Romanian diaspora in the U.S., because many people have family stories similar to my own. There is a yearning to talk about crimes of communist Romania, but our Romanian culture brushes everything – those memories, that inherited trauma – under the rug. I’ve brought the pain to light in my poetry, and I know it has been cathartic for many in my community.

You teach history at Metro State. How does your creative work relate to your teaching? What’s the relationship there?

I am willing to bet I am a pretty unconventional history teacher. I really do not care about dates and names and memorization. What matters to me is critical thinking, making connections, identifying themes, and what we can learn about the past that can help us better understand the world around us, and help us build a better future for all of humankind. I bring my artistic side into the classroom in a number of ways. Given my training as a Shakespearean actress, my students get to see me on my feet “perform” every class. We read rich primary-source materials in class, including plays and poetry. We examine tons of visual art. My students are assigned to write and perform short plays about history. And, of course, we watch movies and documentaries.

I think I am pretty fortunate to teach at Metro. I have to say that MSU Denver is by far my favorite school that I have ever taught at, no offense to all the others. Metro students bring so much to the table and are informed about the world. They don’t take a college degree for granted. I have learned so much these past two years by being in dialogue with these extraordinary young minds. They undoubtedly make me a better person day by day.

People talk about being a Rhodes scholar or winning a Fulbright; you’ve impressively done both. How do awards such as these promote the humanities and liberal arts? How important are they to the furthering of American and worldwide cultures?

I am incredibly grateful for both the Rhodes and the Fulbright, because those scholarships made it possible for me to earn my masters and Ph.D. in history at the University of Oxford. To my knowledge, I am the only Romanian citizen who is a Rhodes scholar. I think that international fellowships will become even more important to preserve graduate study of the humanities. This year has been very difficult for the humanities in U.S. higher education. Entire humanities departments with their tenured professors have been liquidated. Entire colleges have closed down. Even elite schools who are accepting Ph.D. students in the humanities don’t have any way to financially support them throughout their studies. Everyone is basically freaking out about the future of humanities right now. So I see these fellowships as keeping those disciplines alive in some small way.

And even better – they are international. So you get the cross-cultural exchange element as well. The University of Oxford has the most international post-graduate student body in the world. As a Fulbright, I studied at the University of Bucharest – the only American in classes full of Romanians. And yes, these classes were conducted in Romanian, of course! I remember the late Leon Volovici, legendary scholar of anti-Semitism in Romania, checking in throughout the lecture: “Cristina, do you understand?” I think this point about cross-cultural exchange and multiculturalism can answer the question about furthering American and worldwide cultures. International fellowships put us in dialogue with people from all over the world. Studying abroad (because that is what the Rhodes and Fulbright truly are) will broaden all of our horizons. With more knowledge, we are all more powerful. I share this Nelson Mandela quote with all my students: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.”

You have one foot here in Denver and one in Romania. Tell us a little about your cultural background and how that informs your work?

I was raised by an immigrant parent. That was what I was most aware of growing up: people asking my father where he is from; everyone telling me my father had an accent, but I could never hear it myself. I was a child in the ’80s, and the Cold War was still very much going on. My father had fled Romania in 1969 and couldn’t return because Romania was still communist. He never saw his father again. I grew up knowing that my father carried a great burden, and since then, I have devoted a lot of my life to understanding that burden. So until the 1989 Revolution, Romania was forbidden to us. But then the Berlin Wall fell, and Christmas that year, Romania’s dictator, Ceausescu, was killed. After that, Romania opened up to us. And eventually I could start putting all the pieces together of what happened to my family. Many people ask why we weren’t taught Romanian as children. The newer Romanian immigrants, especially, have a hard time understanding this. The answer is simple: Why would we? In the ’80s, the world could never have imagined that Romania would become free. The Romanian language seemed useless. Also, my mom is American – so we spoke the maternal language in the home.

For my mom and her family, life was one big adventure. Her Irish-German-American father from New York City swept my Colorado grandmother off her feet in Grand Central Station. She and my grandfather got married in Denver and [later] moved the family to the East Coast when my grandfather bought a clothing store in Salisbury, Maryland. After that, he worked in professional tennis by managing Jimmy Connors and Ilie Nastase. It was actually my American grandparents knowing Nastase – who is Romanian – that made them comfortable with my dad when my parents started dating.

But despite my parents’ very different upbringings, it is their shared values that most shape me and my work. Education is absolutely at the top of the list. Both my parents earned Ph.D.s. My mom actually submitted her dissertation after having two children. In fact, my father dropped us off at school every morning saying, “Get good grades.” Luckily, I am a total nerd, so studying was always a great joy.

You worked for several years as a researcher for the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. What drew you to that work initially?

My interest in totalitarianism and genocide comes directly from my own family history. Both of my Romanian grandparents were imprisoned by the communist regime simply for not being communists. They were not political people in the slightest. My father’s uncle served on the Canal, Romania’s most notorious labor camp, for ten years and returned to his village. He died shortly after his release, a shell of his former self. Like most people living in totalitarian communist countries, my family was relentlessly spied on, harassed, and followed by the Secret Police, neighbors, and even friends. During this period, even children spied on their own parents and reported it to their teachers in schools run according to communist propaganda. It was a dark, horrible world that my father escaped. And in his bedtime stories to my sister and me growing up, he told us of when his parents were students and in love in Bucharest in the 1930s. “Romania was free then, girls,” he would say. So I always knew that Romania had been a democracy, and I wondered what went wrong. That’s how my Ph.D. topic found me. It was this question of what happened to Romania’s interwar democracy. Fascism took over. I decided to research why Romanian intellectuals supported fascism and not democracy. And then I learned about the Romanian Holocaust.

When I told my father about my research, he was in disbelief. Under communism, the Holocaust had been erased from the history books. He truly had never heard of the Romanian Holocaust until I told him. And that is how I got to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum as a research fellow in 2009. I was there for one year to write my Ph.D. dissertation, which I did. And during that year, the museum was the target for a violent and deadly racist attack by a neo-Nazi, who killed my colleague and friend Stephen Tyrone Johns, who worked at USHMM as a security guard.

So how has contemporary politics affected your thinking about that dark period of history?

We are all in danger of fascism, anti-Semitism, xenophobia and racism every day, all over the world. The events on January 6, in particular, were an opportunity for fascism scholars like myself to share our knowledge on social media, to try to help everyone understand what had happened. With Modi (India) and Bolsonaro (Brazil), we have fascist right-wing leaders currently in power, while Putin (Russia) and Xi Jinping (People’s Republic of China) are well-known authoritarian world leaders. I think my research at USHMM has made me even more aware and more sensitive – and honestly more angry – than I would otherwise be. It is hard to describe to anybody that you spent hours counting just how many people died in a concentration camp.

The worst was when I wrote the entry on the Algerian camp Hajerat M’Guil, known as the Buchenwald of the Sahara. What happened there is so terrible that Westword would not be able to print it. USHMM was a dark place in terms of subject matter, but I derived so much meaning personally, because I felt that I was working on something truly important.

As a fourth-generation Denverite on your mom’s side, what’s changed for the better, do you think?

I learned from my grandmother’s stories – not only from my younger years with her, but also as her roommate, caretaker and best friend in the final three years of her life. She always was very open about the KKK’s control of the state when she was growing up here. According to family legend, my great-uncle arrived in Colorado after emigrating from Denmark, and he was invited to “a community meeting” to welcome him to the area. When he arrived, though, everyone was wearing a white hood. The person at the front of the room started reciting what I gather to be the mission statement of the KKK: listing all the groups that were not welcome according to them. This list included Catholics, of course. The legend has it, as told by my grandmother until she died, that her Danish uncle, in broken English, spoke out and said, “But my niece are a Catholic and she are a good woman!” Whereupon he ripped the hood off the speaker’s head, only to reveal a prominent politician in the town. Granted, this is family lore, so the story could very well be exaggerated, but I do think it shows the power of the Klan in Colorado’s history. I do believe that the state is moving away from that painful past and that there is still so much more work to do to fight for racial equality. Being raised by a grandmother who was openly anti-KKK definitely influenced the way I see the world now.

What place in Denver most inspires your creative and academic work?

Given the pandemic, I have to be honest: I do all my writing at home. My favorite writing spot, hands down, is my own home office. My partner and I moved to Denver exactly two years ago, and last September we moved into our very first house, built in 1890, which we lovingly call “Rainbow House” because it is painted in rainbow colors. My daily inspiration is where we live: this historic and stunning downtown location. Every day my furdaughter, Pickles, and I go on two walks through our neighborhood. I am obsessed with the architecture, the murals, the schools, the parks and the vibrant community. My favorite local spot to hang out is definitely the Whittier Cafe. And my spoken-word home is Creative Strategies for Change, which is my favorite Denver spot to share my poetry, and also the CSC creative community inspires me to no end! I am so grateful I have found that creative home here in Denver.

Cristina Bejan and all the winners and finalists of the Indie Book Awards will be honored at a Facebook Livestream, at 5 p.m. on June 25. For more information on Bejan’s work, see her website.