In his first film since the culture-shaking, Oscar-winning Moonlight, writer-director Barry Jenkins has not so much adapted James Baldwin’s 1974 novel If Beale Street Could Talk as expanded it, in ways only the most accomplished filmmakers can achieve. Baldwin’s central story, dialogue and time-jumping narrative structure are all in place, but so, too, is a sumptuous visual style that serves to deepen the novelist’s themes of racial injustice and the powerful countering force of love.

Jenkins opens on Tish (KiKi Layne), age 19, and Fonny (Stephan James), 22, walking hand in hand through Central Park in the early 1970s. The two played together as children, but on this day — in this moment — they’re discovering that they’ve fallen in love. Tish moves a few paces ahead and turns. In the first of the film’s magnificent close-ups, shot by Moonlight cinematographer James Laxton, Fonny stops and looks at her, his eyes brimming with competing emotions — desire, surprise, love. Tish meets and matches his gaze, and then asks, “You ready for this?”

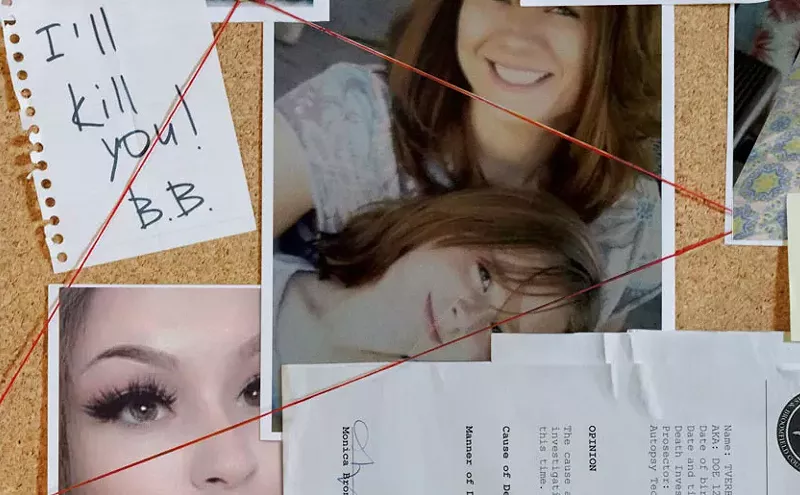

He is, but the very next scene finds Tish, months later, visiting Fonny in jail. In voiceover, she says, “I hope that nobody has ever had to look at anybody they love through glass.” Fonny has been arrested in connection with the rape of a Puerto Rican immigrant (Emily Rios) in the East Village. He has an alibi, but this is America, and an alibi doesn’t count for much when a young black man like Fonny has made an enemy of a white policeman (Ed Skrein).

Tish tells Fonny that she’s pregnant, delighting him. The teen is more nervous about telling her mom, Sharon (Regina King), but she’s pleased, too, and helps Tish break the news to her father, Joseph (Colman Domingo). In a lovely subversion of expectation and cliché, Joseph responds not with anger, but a toast. There is love in this house, and later, we’ll glimpse the erotic heat that still burns between Sharon and Joseph, who surely see themselves in Tish and Fonny.

One of the beautiful things about Jenkins’s brilliantly acted film is the artful economy with which Tish and Fonny and all who love them are given the time and space to reveal their deepest fears and darkest hurts. Meeting in a bar one afternoon, the fathers discuss Fonny and Tish’s dilemmas and wonder if there are limits to what a man will risk to save his child. In a rundown motel room, Sharon, who’s about to confront the woman who has mistakenly identified Fonny as her attacker, stands before a mirror. She’s trying to get her wig just right, only to stop and stare at her own reflection, as if acutely aware, suddenly, that she's completely out of her depth.

And all along, Tish’s mind keeps traveling back to those sweet first months with Fonny. She lost her virginity to him, and their first night together, in his crummy studio apartment, with one lightbulb dangling from the ceiling and rain whooshing against the window panes, is a love scene for the ages. The sound of the rain, intensifying as the two draw closer together, is unforgettable — this is pure cinema.

There’s glory, too, in the film’s rich color palette. In voiceover, Tish calls out the ashen, desolate inner-city landscapes designed to deprive African-Americans of a sense of self-worth. But the delicate yellow wrap she’s wearing as she and Fonny walk the city, and the red umbrella he uses to protect her when it starts to rain repudiate that imposed narrative. Fonny’s green sweater matches the flower vase Tish has placed on their new table, just as the curtains in Sharon’s living room complement the slacks and coat she wears as she unpacks groceries.

As a filmmaker, there’s not a casual bone in Barry Jenkins’s body, making these celebratory design choices feel purposeful, hopeful, and deeply, sweetly, loving. If Beale Street Could Talk does James Baldwin proud.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Billboard - Slot Inline - Content - Labeled - No Desktop",

"component": "23668565",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "STN Player - Float - Mobile Only ",

"component": "23853568",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17242653",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - 2x Rectangles Desktop, Tower on Mobile - Labeled",

"component": "24956856",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18838239",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard to Tower - Slot Auto-select - Labeled",

"component": "17676724",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]