Mr. Kleinman's son, Ira, a good third baseman who tended to step in the bucket, was always in the candy-store group and was always a friend. As shy as his father was flamboyant, Ira Kleinman played hard and said little. Everyone liked him. When he died of leukemia at the age of twelve, we kids were scared. And baffled. And struck by disbelief. For weeks afterward, we expected Ira to materialize on the corner with his crooked grin, tossing a ball into the pocket of his mitt: "Let's play," he would say, and we would then go to our scarred diamond under the long east ramp of the Triborough Bridge and, with traffic thrumming overhead, play until dark.

Instead, one day sometime later, I went with my father to Mr. Kleinman's office in Ozone Park. That visit remains as vivid as the day JFK was shot, or the night my father suddenly died, or September 11th. On Mr. Kleinman's rich cherry-wood walls hung an impressive array of framed degrees (Cornell, Columbia) scripted in Latin, a dozen civic awards and some casual pictures: Mr. Kleinman with Adam Clayton Powell; Mr. Kleinman with Moose Skowron, the Yankees first baseman; Mr. Kleinman with my father and Jack Dempsey, each handsomely suited man smiling and holding a highball. On Mr. Kleinman's desk there was a photograph of Mrs. Kleinman, a spectacularly beautiful woman in the style of Jane Russell -- and a silver-framed photograph of Ira Kleinman, age eight or nine, sitting alone and looking dreamy in his baseball cap.

In Mr. Kleinman's palm, turning and turning, I saw a bright white, red-laced baseball.

"Doc," he said, rising to greet my father. "Nice to see you." He extended his impeccably tailored arms, and the two friends briefly embraced. "And young Bill! How are you, slugger?" The baseball kept turning in Mr. Kleinman's hand, and when he came to hug me, I sniffed the dangerous odor of gin. For a while the men talked (uncomfortably, I thought), and when at last my father and I got up to leave, I saw the flash of so stricken a look pass over Mr. Kleinman's face that I have never forgotten it. His hand, the one holding the baseball, lingered on my shoulder, and even now I can smell the gin.

This is a roundabout way, I suppose, of reminding myself -- and maybe you, too -- that the outside of a horsehide (to corrupt Winston Churchill) can do wonders for the inside of a man. I don't know how many days or months or years Mr. Kleinman sought to comfort himself with the ancient textures of a baseball cupped in his hand -- the rippled sheen of the hide, the 216 laces, the familiar five-ounce heft -- nor can I presume to measure the depth of his grief. But I do understand the secret pleasures of flipping a baseball hand to hand, of roughing up the surface between the palms like Nolan Ryan in stern concentration. Anyone who once played the game at any level and continues to love it understands the pleasures of the baseball itself -- yes, they verge into the sensual -- of absentmindedly soft-tossing the thing into the air and performing assorted bare-handed catches, plain and fancy, in a reverie that can suddenly uncloud muddled thought. Any player of old grasps the way playing mindless flip-and-catch with an office colleague can bring new focus to jangled senses. A baseball is not just a talisman. It's an object of contemplation that, by the simple act of handling it, can produce something like a religious experience. Ask anyone who keeps a Rawlings or a Spalding on his desk. Mr. Kleinman knew what he was doing.

These things come to mind today because, amid the fascinating and unpredictable World Series just now completed, the baseball itself came under special scrutiny. Furthermore, just beyond the home parks of the Anaheim Angels and the San Francisco Giants, some baseballs that have much greater totemic value than that smudged and beaten old favorite on your coffee table remain disputed objects of desire.

By the time this Hotel California Series got to Game 2, an 11-10 slugfest featuring five home runs, some players on both teams -- pitchers, mostly -- started speculating that the baseballs being used in the games were wound tighter than Bud Selig's psyche. In the Official Baseball Rules, section 1.09 states that "the ball should be a sphere formed by yarn wound around a small sphere of cork, rubber, or similar material covered with two strips of white horsehide or cowhide, tightly stitched together." Today's ball has a cork nucleus encased in rubber, wound with 121 yards of blue-gray yarn, 45 yards of white wool yarn and 150 yards of fine cotton yarn, covered in hand-stitched cowhide.

However, the tighter the ball is wound, the harder it is, and the farther it will travel when struck. Giants and Angels pitchers alike -- men intimately familiar with the spins and flights of the baseball -- all said the World Series model was hard as a rock and thus as jumpy as a rabbit. Like the balls alleged to be used in the great Sammy Sosa-Mark McGwire home-run derby of 1998 -- the circus that re-energized the game after four years of strike-induced ill feeling -- this year's Series balls were said to be "juiced." More scoring, after all, means higher TV ratings.

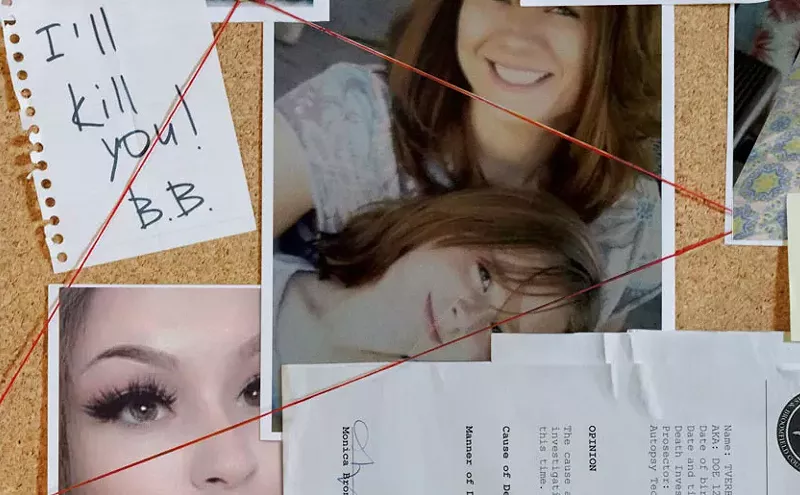

And even as the Angels pitching staff was making every reasonable effort to keep the baseball beyond the range of slugger Barry Bonds's lethal bat (BB's not just the Sultan of Swat; he's the ultimate Walkman), a few yarn-wound orbs that did enter his killing zone recently found themselves in court, of all places. Two weeks ago, a nasty feud over Bonds's record 73rd home-run ball of 2001 (estimated value: over $150,000) went to trial in San Francisco, while the four fans wrangling over Bonds's 600th career dinger -- struck this year -- managed to resolve their dispute amicably. At the same time, a real-estate investor who fought off five other fans to snag Bonds's 485-foot monster homer in Game 2 of the World Series displayed admirable selflessness: David Behrend said he would donate that ball, which could bring $8,000 to $10,000 (up to $15,000 if Barry signs it) to a cancer-research foundation.

Meanwhile, a fast-food chain installed a fifteen-foot floating target in the waters of McCovey Cove, beyond the right-field bleachers of San Francisco's Pac Bell Park, pledging that if any player hit the thing with a home-run ball during the Series (no one did), every last American who wanted one would get a free taco.

Juiced baseballs. Taco giveaways. Fans screaming at each other over retrieved home-run shots. What would Morris Kleinman, the brilliant lawyer, make of all that? And what would he make of Ken Lee, the California business executive who recently paid $93,000 for a baseball signed by members of the 1919 Chicago "Black Sox" team, eight members of which threw the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. Until recently, Lee kept the ball in a humidor (a concept familiar to Colorado Rockies fans) in his home. Now it's in a safe-deposit box and will remain there until 2019, the 100th anniversary of the Black Sox scandal. At that time, Lee plans to sell it. Until then, he probably won't be soft-tossing his valuable relic of big-league infamy to his co-workers at the office, or rubbing it up preparatory to imitating Eddie Cicotte's windup.

Now that we fans face another long winter without the game, I cannot help but think of Mr. Kleinman that day in his office and his effort at comfort. He knew it. Barry Bonds knows it. We all know it. Every time you grip a baseball, you realize what a powerful grip baseball has on you -- player strikes, outrageous salaries and $7 ballpark beers notwithstanding.

See you next April.