Scott Lentz

Audio By Carbonatix

The City of Denver’s ongoing fight against Sweet Leaf has plenty of video evidence and witness testimony on its side, so why is it using an unexpected legal argument to strip the Denver-based dispensary chain of its 26 cannabis-business licenses? Denver attorneys are now using a new strategy, heavy on the word “complicity,” to go after alleged bad actors on the pot scene, but the other side sees the switch as a sign of a weakening case.

On March 14, hearing officer Suzanne Fasing began hearing testimony regarding the city’s suspension of all Sweet Leaf licenses after the Denver Police Department and other state and local law enforcement agencies raided eight of the company’s dispensaries on December 14. The hearing was supposed to take two days, but it’s already been extended into next week. Ultimately, Fasing will recommend whether to reinstate the Sweet Leaf licenses – or terminate them for good.

Appearing in a Denver Department of Excise and Licenses hearing room this week, lawyers representing Sweet Leaf defended the company from allegations that it had enabled illegal cannabis purchases by customers. The December 14 raids came after a year of investigating alleged looping, or selling unlawful amounts of cannabis to customers, at Sweet Leaf stores, according to the Denver District Attorney’s Office.

For the better part of two days, DPD detective Aaron Kafer provided extensive recordings of police officers making repeated undercover purchases at Sweet Leaf, as well as interviews with suspected loopers after their arrests. The undercover officers made seven purchases in the same day during their first foray; Sweet Leaf employees reportedly told suspected loopers to park out of sight from the store cameras. Some customers bought anywhere from two to ten pounds over the course of several hours, Kafer testified. Under the language of Amendment 64, a customer is only allowed to buy one ounce at a time – and as of January 1, 2018, a new law clarifies that a customer is only allowed to buy one ounce per day. But these purchases were made before then, in 2016 and 2017.

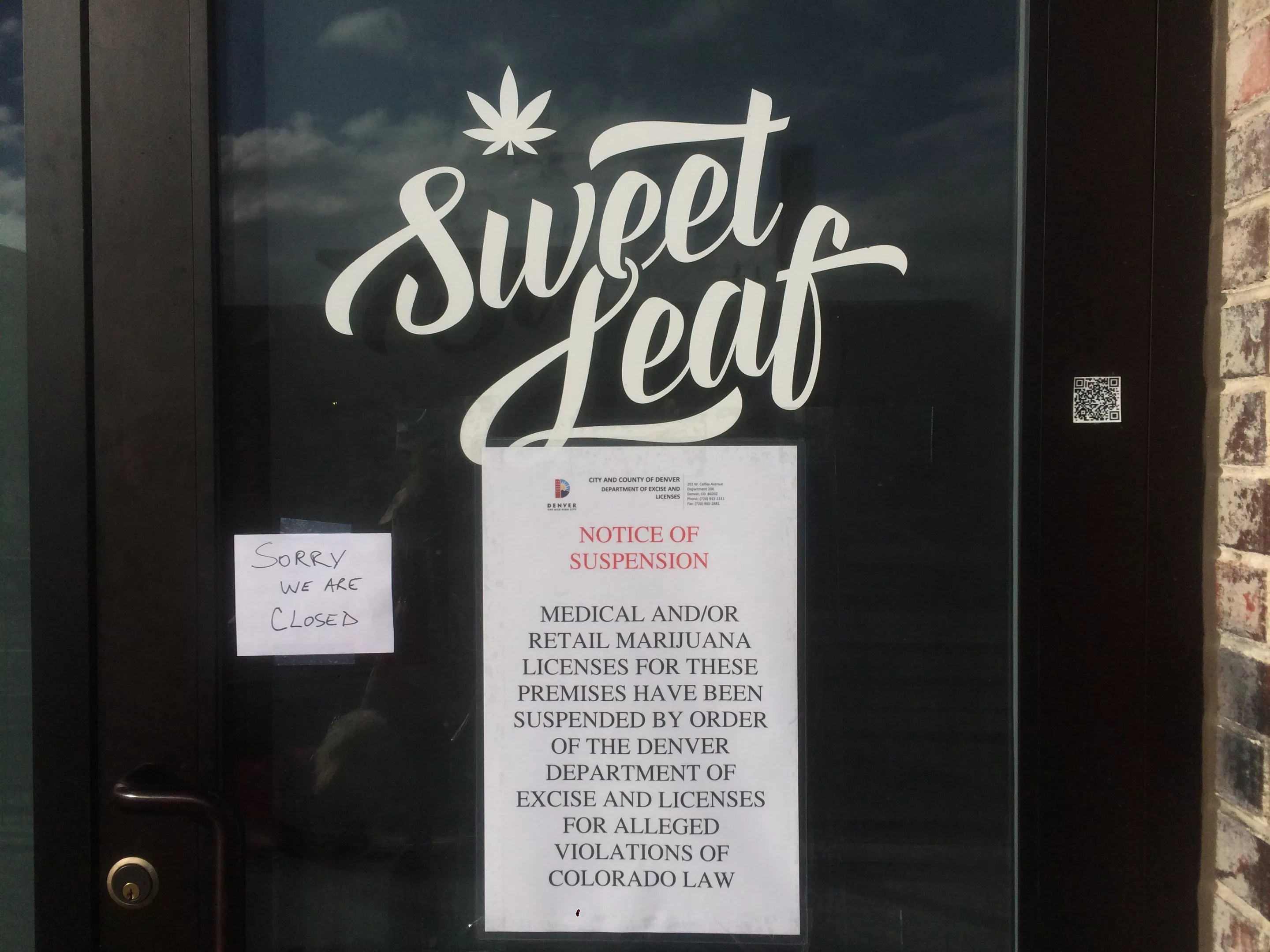

All seven Sweet Leaf dispensaries in Denver remain closed.

Scott Lentz

“All of the purchases were for one ounce,” Tom Downey, an attorney representing Sweet Leaf, noted multiple times during the hearing. This key distinction has created a tougher battle than anticipated in the city’s quest to shut down Sweet Leaf’s business licenses, as well as the DA’s prosecution of the fifteen budtenders arrested in connection with the looping investigation. Much like its argument in the case charging the International Church of Cannabis with alleged public cannabis consumption violations (which ended in a mistrial in February), the city is now claiming that Sweet Leaf and its employees were complicit in other people breaking the law. And, as with the church case, the word “complicity” was a relatively recent addition to the argument, after months of legal battle. Now, both cases may hinge on it.

The tactic is relatively new to cannabis cases involving businesses and organizations, according to Sam Kamin, professor of marijuana law at the University of Denver Sturm College of Law. Kamin, who was set to testify on Sweet Leaf’s behalf on March 14 but whose appearance was pushed back as the city presented its case, believes the “complicit” strategy stems from insufficient charges by the Denver District Attorney’s Office.

“The way I read the regulations of that statute [in Amendment 64], I didn’t see what they had done to violate it. The rules didn’t say no more than one ounce per day; it’s per transaction,” Kamin says. “There doesn’t seem to be any allegation that they sold more than one ounce to a customer during any transaction – so that leads to the question: How do they justify cracking down on Sweet Leaf and these budtenders?”

The city argues that when Sweet Leaf budtenders were selling one ounce of cannabis to the same customers multiple times a day, they were breaking the law. However, Sweet Leaf has denied any wrongdoing, arguing that the language of the law tied the one-ounce limit to individual transactions, not accumulative transactions each day.

A sign at Sweet Leaf’s Walnut Street dispensary announces the store’s license suspension.

Thomas Mitchell

The five budtenders originally facing felony cases each saw their charges of distribution of marijuana (more than four ounces/less than twelve ounces) dismissed between late February and early March, only to see two new counts added against them: possession with intent to manufacture or distribute marijuana (more than four ounces/less than twelve ounces) and possession of marijuana (more than two ounces/not more than six ounces). In essence, the DA is now claiming that they were complicit in the customers breaking the law, thus breaking the law themselves.

“At first I didn’t understand what they were doing, because it seemed like [Sweet Leaf] had complied with state law,” Kamin says of Denver’s initial charges. “But if they’re saying each sale led to illegal posession, then that’s different.” Even with the new argument, Kamin thinks that Denver is overstepping its bounds with both the budtenders and the businesses itself.

“I’m really skeptical about it. You have to show there was intent – that for some reason, the budtenders wanted to facilitate possession that was illegal, which I doubt can be done,” he says. “And there’s language in Amendment 64 that says you can’t pursue criminal charges like these on licensed individuals.”

Both the DA and Excise and Licenses declined to comment on the cases. Sweet Leaf has not responded to recent requests for comment, but has previously denied any wrongdoing. Anthony Sauro, Christian Johnson and Matthew Aiken, the dispensary chain’s owners listed in the city’s suspension order, have not been arrested or charged. The fifteen budtenders who were are still awaiting trial.