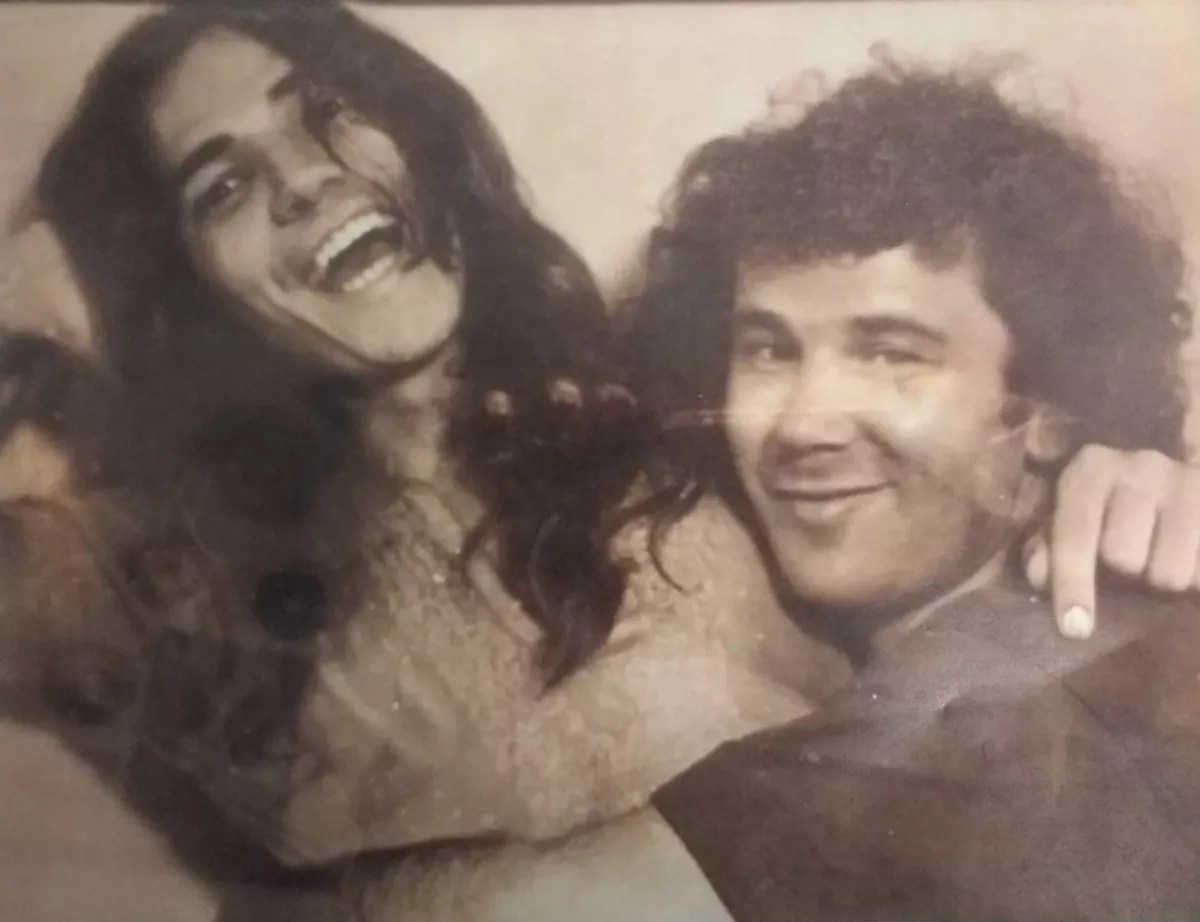

Courtesy of Chuck Morris

Audio By Carbonatix

In 1976, guitarist Tommy Bolin died of an overdose at 25 years old. In his short life, he’d made two albums with Zephyr and two records with the James Gang; played on Billy Cobham‘s jazz-fusion masterpiece, Spectrum; replaced Ritchie Blackmore in Deep Purple; and released two albums under his own name.

It all started in 1967, when Bolin was a teenager. He bought a one-way bus ticket to Denver from his home town of Sioux City, Iowa, after getting suspended from Central High School twice for his hair being too long – the second time after cutting it, apparently not short enough. Bolin had heard about the Denver music scene from a childhood friend who had moved here.

After a few years in Colorado, Bolin found a place in Boulder, where he met Chuck Morris, now the head of AEG Presents Rocky Mountains, who was managing the bar at the Sink, a Boulder classic, at the time. Morris remembers Bolin showing up at the Sink and playing for him. “He was just a genius musician,” Morris says. “You could tell right away he was one in a million.”

Morris says he’s promoted some of the best guitarists in the world, but he’s never seen a guitar player better than Bolin, who is shortlisted to be inducted into the Colorado Music Hall of Fame.

“If Tommy Bolin was alive today, he’d be Eric Clapton in terms of his wealth of music and his popularity,” Morris says. “I don’t think there’s any question about it. He was a brilliant guitar player who could do anything with that instrument. I mean, yes, there were others, don’t get me wrong; I’ve worked with most of them. But he could do anything with a stringed instrument at a very, very early age.”

On Friday, March 30, musicians who collaborated with Bolin in various bands are teaming up for a tribute to the guitarist dubbed Tommy Bolin’s Dreamers. In the mix: Bolin’s brother Johnnie (a part of Tommy’s band and a member of Black Oak Arkansas for thirty years), bassist Stanley Sheldon (a longtime member of Peter Frampton’s band), drummer Bobby Berge, vocalist Jeff Cook and singer/keyboardist Max Carl (of Grand Funk Railroad). Filling in for Bolin will be guitarist and singer Lucas Parker, who is 25, the same age Bolin was when he died.

“I’ve been waiting a long time for someone who could step into Tommy’s shoes, and I wasn’t sure I’d ever meet anyone,” Sheldon says. “Just so happened he was my student. He’s an incredibly talented guitarist.”

Parker has some big shoes to fill. Sheldon says Bolin was innovative at such a young age, and fearless about what he wanted to do on the guitar.

“He’d been hanging out with these jazz superstars, so he had all the improvisational desire, and he had the technical ability to just execute just about any lick that he could imagine in his head,” Sheldon says. “And that’s what made him special, and that’s what attracted people like Jeff Beck to him. Later on, when he did that Spectrum album, all the guitar players in the world took notice. It was a pretty special time. He had such a good ear he didn’t need to read music. A lot of us didn’t, but Tommy especially didn’t, because he was just so skillful.”

Before he started playing guitar when he was eleven, Bolin was attending concerts with his father, Rich, who instilled a love of music in his son; the two saw Elvis Presley together when Tommy was just five.

“Dad was a music fan,” says Johnnie Bolin. “He didn’t play anything, but he had a dream that he wanted Tommy to be the next Elvis. So he got Tommy pantomiming when he was five years old. I have several pictures of Tommy pantomiming to Elvis. He had a leather jacket. He had jet-black hair anyway. It was slicked back.”

Bolin first learned Hawaiian steel guitar from Ray Flood at Flood Music in Sioux City, and then took lessons from a country-Western guitarist who lived across the street from his house. He eventually started playing along with Rolling Stones albums.

“He used to listen to jazz when he was a kid,” Johnnie Bolin says. “It was all about Elvis at first, and the Ventures and the Beatles and Stones. But he had another side to him where he really enjoyed jazz.”

While Bolin was a chameleonic player who knew his way around rock, jazz, blues, funk, reggae and a lot more, Morris was blown away by Bolin’s lap-steel playing.

“I’ll never forget this,” Morris says. “We used to have a talent night at [former Boulder club] Tulagi where anybody could get on stage. We had a country band there, and I was hanging out with Bolin. It was probably ’71 or ’72. He said, ‘I’m going to go up there and jam with these guys.’ He went up there, there was a steel guitar sitting there, and he played steel guitar as if he’d played it for fifteen years. And that’s one of the toughest instruments to play. I said, ‘Tommy, how the fuck did you learn how to play steel guitar?’ He said, ‘I’ve been playing around with it just a little bit.’ He was unreal.”

When Morris took over Tulagi in Boulder in 1970, he recruited Bolin’s psych-rock/blues act Zephyr to play the club’s opening night. When Bolin was gigging during the early days of Zephyr, he spent a lot of time at Tulagi, either jamming or just hanging out, seeing blues masters like Muddy Waters and Lightnin’ Hopkins, rock acts like ZZ Top and the Doobie Brothers, and jazz legends including Eddie Harris and Cannonball Adderley.

“If he wasn’t on the road or wasn’t playing, he’d come to all those shows and hang out with me,” Morris says. “And so we became good friends. He was such a sweetheart.”

In 1971, Zephyr went to Electric Lady Studios to record Going Back to Colorado, the band’s second album, with Jimi Hendrix engineer Eddie Kramer. Sheldon, who had moved from Kansas City to Boulder around that time, originally met Bolin through a musician in the band, Amadeus, who put him on the phone with Bolin. Not long after that, the two formed the metal-fusion band Energy, with singer Jeff Cook and Sheldon’s cousin Tom Stephenson.

When Energy first started touring, Sheldon recalls, the band played in some tiny, divey bars in places like Pueblo, Colorado Springs and Cheyenne.

“Every gig was incredible,” Sheldon says. “None of those gigs were recorded, unfortunately, but everyone…we were all getting high, we weren’t prescient enough to think, ‘Hey, let’s record this.’ But those were probably the greatest shows that Tommy ever played, and no one will ever hear it.”

Morris had also booked Energy to open for legendary bluesman John Lee Hooker for a week at Tulagi and to open for Albert King at Folsom Field.

“[King] and Tommy just bonded like crazy at that gig, and again, it wasn’t recorded,” Sheldon says. “It was a fantastic show. Tommy and Albert were laughing and joking with each other on stage about Tommy’s gadget, the Echoplex. Albert King would say, ‘Man, that’s pretty impressive what you’re doing, but you got that box!'”

The Maestro Echoplex was a tape-delay effect that Bolin used as part of his trademark tone and for the “ray-gun” effect on the Spectrum album. He was also using it during some of the many gigs that Energy played at Ebbets Field, the downtown Denver venue that Morris and famed promoter Barry Fey opened in the early ’70s after Morris left Tulagi. Morris says it was at the venue – named after the famed ballpark in his native Brooklyn – where Energy “really got their chops together as a band.”

Johnnie Bolin says that even when his brother left Energy to join the James Gang and then later rejoined the former band, he still wanted to form his own group. Just after the release of Bolin’s remarkable debut, Teaser, he was asked to join Deep Purple in 1975.

“And he’s like, ‘I finally got my own album; now these guys want me join them,'” Johnnie Bolin says. “Well, you don’t turn down a gig with Deep Purple. But he didn’t want to be with Ritchie [Blackmore] and he didn’t want to be with Joe Walsh. He wanted to be with Tommy. That’s who he was.”

In 1976, the year that Bolin died, he befriended Exorcist actress Linda Blair, who let him stay at her Beverly Hills house for a while; he also recruited Johnnie to play drums in his band. He released his final album, Private Eyes, that year, but after the first show of what was to be a promotional tour for the album, he died after overdosing on heroin.

Fey, who had been managing Bolin, called Morris early on the morning of December 4.

“I’ll never forget,” Morris says. “Barry was not a crier. He called me crying on the phone. I’ll never forget that as long as I live. It was hard to hear what he was saying. And then he calmed down a little and said, ‘Tommy died.'”

Tommy Bolin’s Dreamers, 8 p.m. Friday, March 30, Boulder Theater, 2032 14th Street, Boulder, $25-$75, 303-786-7030.