Ayah Al-Masyabi

Audio By Carbonatix

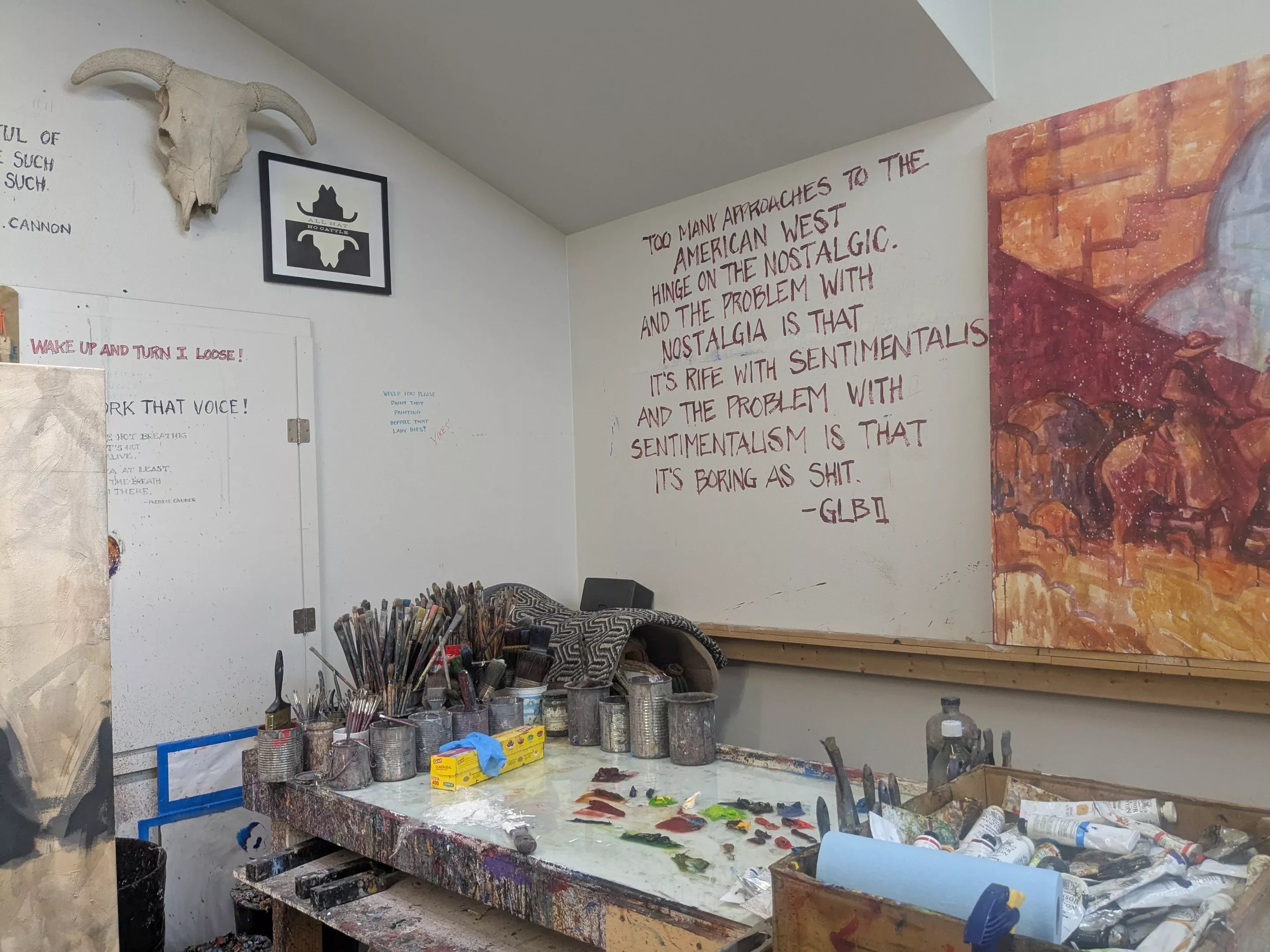

Walking into Duke Beardsley‘s Denver studio, two things quickly become clear: This is the home of an artist and of a cowboy. Both are identities that Beardsley inhabits with equal parts pride and uncertainty.

Beardsley says that ranching culture has always been a part of his life and his work, but his spin on the genre of Western art isn’t nostalgic – it is a contemporary take on life between ranch and urban spaces. Beardsley allows for tradition in his work, but he also challenges the past, imagines the present and constantly questions the romanticization of the West.

Although Beardsley is very modest about his many achievements, his work has earned recognition across Colorado, the West and internationally. A recipient of the Colorado Governor’s Art Award, his art has appeared in numerous regional and national exhibitions, including the Coors Western Art Exhibit & Sale, where he was the featured artist in 2025.

Beardsley’s art has been displayed across a number of collections and museums, including the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum.

Ayah Al-Masyabi

His work has also been displayed in a number of collections and museums, including the Petrie Institute of Western American Art at the Denver Art Museum. His acclaimed drawings in paint capture the elements of the West in a figurative manner with a contemporary twist.

Descended from a family tradition of ranching for over four generations, Beardsley’s paternal grandfather bought a ranch in the southeast corner of Douglas County in 1969, the year Beardsley was born. His father had a job in the city and Beardsley went to school in Denver, but on weekends, holidays and summers, “we all convened at this cattle ranch,” he recalls. When he was a kid, scenes from the ranch were all he drew – and he was good at it.

“I think I was three or four years old, and my grandparents took my sister and I to the zoo,” Beardsley remembers. “And I came back to their house, sitting on the floor in my grandfather’s study, while he read the paper, drawing lions, giraffes and elephants that we had just seen… I remember my grandfather looking over the edge of his newspaper, and I looked up at him, and he looked up at me, and he was like, ‘Hmmm! Wow.’ Then he turned over his paper.”

Beardsley drew “feverishly” as a kid, he says, and it was encouraged. Art was always around him; his parents loved art and even had a modest collection.

“Economies come and go, wars come and go — art is consistent.”

Ayah Al-Masyabi

That early exposure shaped his view of art as something powerful. Two memories stick out as particularly important in the start of his love affair with Western art: finding a book of Frederic Remington’s paintings, and his father showing him the painting “When Shadows Hint Death” by Charles Russell.

“It’s a painting of two mountain men back in the old Western days, and they are off their horses walking next to them. They are clearly placed down in an arroyo. They seem very alert, and they are reaching up and pinching the bridges of their horses’ noses,” Beardsley recalls.

As a kid, he never understood the painting, which also depicts the shadows of Native Americans riding above the mountain men on the other face of the rock wall. Beardsley says his dad explained that the subjects of the painting are pinching the nostrils of their horses because if the horses whinny, the Native Americans will come and kill them.

“When I figured all of that out, that painting scared the shit out of me! It just terrified me,” Beardsley says. “It captured my imagination permanently. The power of visual storytelling, as a ten-year-old, to be that moved and emotional about a painting, really hooked me.”

“Three out of ten cowboys were African American and, I think, one out of three were Hispanic. And the rest of them were every culture imaginable.”

Ayah Al-Masyabi

Beardsley drew nonstop through high school and went to college on the East Coast, where he studied art history and education at Middlebury College, an experience that opened his eyes to the art world and “changed everything,” he says. It was the first time he came face-to-face with just how big art was – for the world, history and humans in general.

“Economies come and go, wars come and go – art is consistent,” he says. “And it has been since we have been painting on cave walls with berry juice. Since human beings have been here, we have been expressing ourselves, and we will always… I think that’s fascinating.”

After graduating, Beardsley came back to Colorado and spent time as an EMT; later, he did a stint in L.A. at a pre-med program. But he still came back to art.

A family friend encouraged him to check out the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena. Beardsley fondly remembers the first moment he went to the school: “I walked into the door, and the first thing I encountered was the student gallery… a beautiful exhibition space of work made by 19-to-25-year-olds.”

He enrolled and immediately felt out of his depth. As an older student, he was acutely aware of the talent of his peers, admitting that “there were 18-year-olds that had way more training than I ever had.”

Beardsley’s acclaimed drawings in paint capture the elements of the West in a figurative manner with a contemporary twist.

Ayah Al-Masyabi

This was further uncovered as he began his educational journey. “I’ll never forget the first day of my first figurative drawing class… we were there from nine-to-four with this intense guy, Scott Hess,” a famed surrealist painter. There were three models, and Hess led them through 20-second poses nonstop for hours. “He drilled us that day,” Beardsley says. “He was like a taskmaster; he might as well have had a ruler in his hand… He would walk by and be like, ‘No! No! Terrible!’ He was ripping us apart.”

Finally, there was a break, but there was a catch: “There were literally sheets covering the floor, and he was like, ‘Pick out one that is acceptable and put it on the crit rail.’ We were so freaked out. They were all terrible,” Beardsley recals.

“He walks down, like some kind of drill sergeant… And he turns around and, suddenly really gentlemanly, he goes, ‘Was this hard?’ We’re all like, ‘Yeah!’ He said, ‘No, I mean, was putting it up on the crit rail? Was that difficult? Is it making you feel sick?’ All of us said yes. He said, ‘All right. Then you need to go upstairs and get your money back. You’re in the wrong place. This is the point.'”

It was the best thing he could have said, Beardsley admits, because it fueled the fire that was already under him. “It was amazing how badly I wanted to do well,” he says. He became intimidated and competitive, and it helped formed him into the artist he is today.

Beardsley sent some of that work to an alumni art show at his high school, and he got a phone call one night from a woman in Denver. She told him, “You don’t know me, but I know your folks. I have a gallery in Denver, and I was just at the alumni show at Kent. I love what you’re doing. When you get out of school, if you want to have a show, let me know.”

When the time came, he took the gallery, Elizabeth Schlosser Fine Art, up on that offer. He went to a branding, spent time with his subjects and took photos to capture the movement and feelings of cowboys. Beardsley painted, painted and painted, mainly drawing on inspiration from his photos. After settling on forty pieces, the gallery held a show and sold everything. “I was like, ‘Hey, that was cool,'” Beardsley says.

“I think artists are magic, they are special — I would like to be considered an artist, I really would. I would love to hear myself tell myself that I am one, but it still feels like I am trying to earn the privilege.”

Ayah Al-Masyabi

Nearly three decades and many accomplishments later, Beardsley still feels like he’s trying to earn the title of “artist.”

“I think artists are magic, they are special – I would like to be considered an artist, I really would. I would love to hear myself tell myself that I am one, but it still feels like I am trying to earn the privilege,” he says.

That confession leads into the stories he is telling through his work, a complex reality that he feels is going through an “interesting” period. “It’s always been kind of a fabricated narrative… In our current weird world, we have lost sight of the fact that cowboy culture was always an immigrant culture,” Beardsley says.

Beardsley believes that the true golden era of cowboys was between 1865 and 1910, when, after the Civil War, waves of people moved west for opportunities. That also coincided with Mexican farmers moving north.

“That’s where the big cattle drives came from and the big ranches were born,” he says. “Three out of ten cowboys were African American and, I think, one out of three were Hispanic. And the rest of them were every culture imaginable.”

Looking at his old works and seeing the milestones within them, like when he first began using color, Duke Beardsley is ready for his art to continue evolving. He is ready to experiment. He is excited to use his artistic voice to challenge and push the boundaries of what is considered Western art.

A layered identity between cowboy and artist, tradition and modern, past and present, is what Beardsley paints over and over again. Never to simplify, but to expose important questions and assumptions.

You can find out more at Duke Beardsley’s work on his website or his Instagram @dukebeardsleystudio.