Audio By Carbonatix

Among the most controversial issues on the November 2018 Colorado ballot is Amendment 73, a $1.6 billion school funding measure.

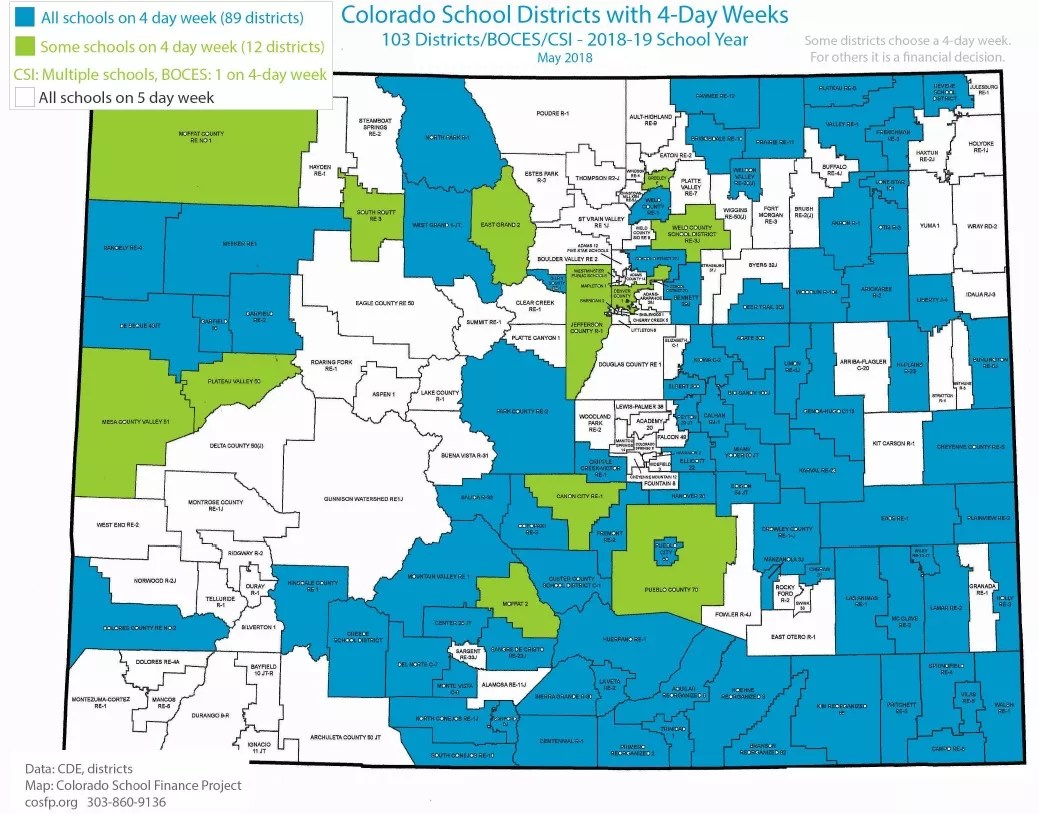

But while proponents and opponents argue about whether increasing taxes for those earning more than $150,000 per year is necessary to improve education in the state, a single statistic speaks volumes about how dire the situation has become: Half of Colorado’s school districts — 89 of 178 — have instituted four-day school weeks, and some schools in more than a dozen others use the schedule, too.

This number has grown substantially in recent years, notes Tracie Rainey, executive director of the Colorado School Finance Project, which backs Amendment 73.

“I think we’ve had quite a few districts that have always had a four-day week,” Rainey acknowledges. “They did that from an agricultural standpoint, or because it was a resort area. But since the recession [in 2008], we’ve seen districts move to it because they’re trying to save money. By going to a four-day week, they’re cutting light usage for a day or lowering various types of infrastructure costs.”

Such decisions are also being made in “districts that have had unsuccessful elections, where they were trying to raise mill levies,” she continues. “Or they haven’t been able to recruit and retain enough teachers, and districts are moving to it as an incentive — because a four-day week may let teachers take a second job. It’s not that teachers in these districts are getting more time off. They’re usually working four days at school and two days somewhere else.”

This Colorado School Finance Project graphic shows the number of school districts in the state operating on four-day weeks in 2018-2019.

Another motivator, in Rainey’s opinion, is the “negative factor,” a school funding mechanism used at the state legislature in conjunction with Colorado’s School Finance Act. Under its provisions, according to the Great Education Colorado website, “the legislature…decides how much it wants to spend on school finance, and then adjusts the negative factor to meet that funding target.”

“The negative factor, which is also referred to as the budget stabilization factor, has been in place since 2009, and it’s led to a decade of underfunding schools,” Colorado Education Association president Amie Baca-Oehlert told us for a post back in April. “This year, the negative factor has grown to $822 million, but over the last ten years, it adds up to $6.6 billion. That means some students have spent their entire K-12 education experience at underfunded schools.”

All of these elements have what Rainey describes as “a cumulative effect on districts. When the budget stabilization factor started, districts thought, ‘We’ll have this for a year or two, so we’ll take some money out of reserves or maybe we won’t hire as many people.’ But ten years down the road, we’re continuing to increase student population across the state, we’ve become less competitive for teacher salaries and we have more students with higher needs. Those things compound each other to create a dynamic where districts are now saying, ‘Our choices are very limited. Do we move to a four-day week that allows us to try to keep cuts away from classrooms as much as we can?'”

Such moves make economic sense, but Rainey says “that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a good educational model, especially if you’re a district with a lot of students who have high needs. Many of them become dependent on school districts for food — for breakfast and lunch. Now you’ve created a situation where there aren’t systems in place to help the neediest children.”

Districts that have gone to four-day weeks haven’t necessarily reached the stage where they’re cutting teacher salaries, Rainey believes, “but they haven’t been able to increase them. In those areas, finding teachers who offer specialized services, whether it’s a psychologist or a reading specialist or a number of other positions, has been incredibly difficult for a while. And now we’re hearing administrators saying, ‘I can’t even find a math teacher or a Spanish teacher.'”

Colorado School Finance Project executive director Tracie Rainey.

Another shift: Whereas four-day school weeks have been a way of life for some time in rural areas, more districts with larger populations are moving in this direction. Rainey cites Brighton, Sterling and Pueblo.

“Before, four-day weeks weren’t hitting the radar screen in some of the more metropolitan districts,” she maintains. “But now they are, and that means more kids are being impacted — and the local economy is, too. What effect does that have on housing development? Is a builder going to say, ‘Do we really want to build here if we have to tell people the schools are on four-day weeks?'”

Rainey refrains from criticizing districts that are eliminating a day of coursework per week. She feels the ones with which she’s familiar are working hard to “ensure that the quality of programs and the dynamic nature of the programs they’re delivering are meeting the needs of their students.” At the same time, though, she wonders if this tack “is going to make students less competitive in a global environment, less able to enter the workforce or be ready for some type of additional education. I don’t think there’s enough research available to tell us that yet. Everything is pretty much opinion-based or anecdotal. But if you look at the systems worldwide that are doing better, they’re all on longer days and longer weeks.”

If Amendment 73 passes, individual districts will be able to determine where to apply the extra funding. Rainey suspects that some of them will use the money in an effort to return to a five-day week, while others will have different priorities. “There are so many needs,” she says.

On that, most Coloradans agree, whether they favor Amendment 73 or not.