Nicholas Ward

Audio By Carbonatix

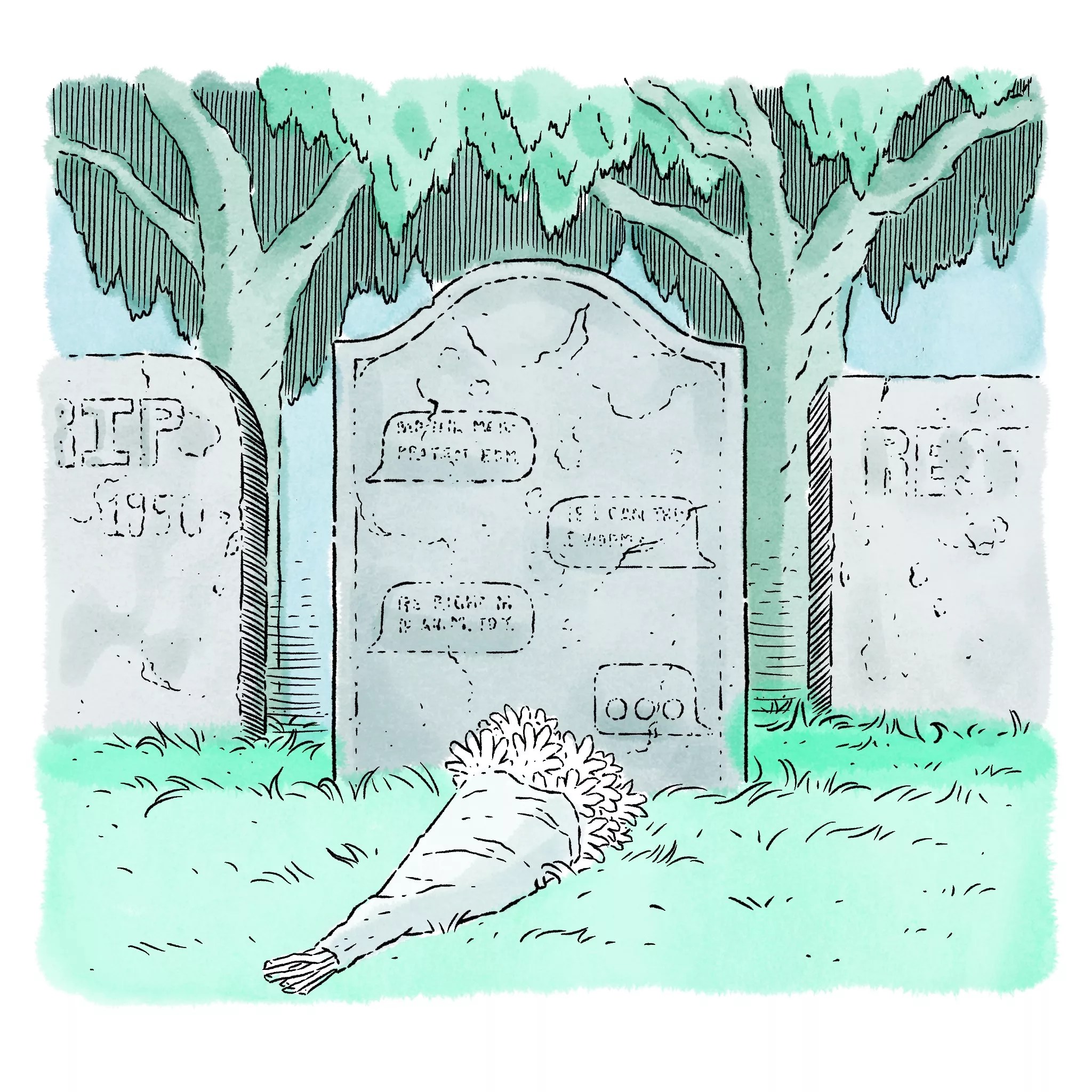

Jed Brubaker sees ghosts in his lab. To be specific, this professor of Information Science at the University of Colorado Boulder is studying generative ghosts, AI versions of deceased people, and how they may develop as we move toward the technological horizon of generative AI.

His study goes beyond those griefbots that feed back prerecorded thoughts or memories to a grieving loved one. Brubaker’s focus is on AI ghosts that can create novel content, hence the term “generative ghosts.” A generative ghost could give a user perspective on current events that its human basis never witnessed, or offer advice on stock moves given the day’s markets.

It sounds a bit creepy, to be honest, but Brubaker says that reaction is predictable when we’re not acclimated to a technology. “If we think through the history of death and technology, there was an era when video was uncomfortable for people,” he says. “Prior to that, there was an era when photos were a little creepy – were they stealing someone’s soul? What happens is, with each new medium it takes us a little while to figure out and interpret what’s happening there.”

Brubaker has been working at this intersection of technology and mortality for sixteen years; he was the lead researcher for Facebook’s legacy contact program, the system that lets a loved one take over a dead user’s account and make it a memorial page. “I’m the intersection between a psychologist and a computer scientist, and these types of things tend to be right up my alley,” he says.

Brubaker teamed up with a Google DeepMind researcher, Meredith Ringel Morris, to write a new paper, “Generative Ghosts: Anticipating Benefits and Risks of AI Afterlives.” According to him, the difference between so-called griefbots or deathbots and generative ghosts is like the difference between a search engine and ChatGPT, where ChatGPT has a voice and can converse.

The applications go well beyond alleviating the grieving, though. “Khan Academy now has developed a virtual Benjamin Franklin as part of their teaching systems,” he notes. “We would consider that a type of generative ghost.”

CU Boulder Information Science professor Jed Brubaker sees AI ghosts.

CU Boulder

He points out the value of generative ghosts to museums and learning institutions, and says that Holocaust museums in particular are fascinated with the potential of generative ghosts.

But the realm is thick with philosophical questions and potential pitfalls, as the paper makes clear. What are the ethics of third-party generative ghosts created by someone else versus first-party, for which the deceased person created the ghost before passing on? Should a generative ghost be a reincarnation or a representation? Should it use the first person? Will the generative ghost remain static or develop novel interests and skills, evolving away from the deceased individual’s traits?

Besides these speculative design questions, which Brubaker pursues in his academic work, the paper examines a list of potential benefits and risks. Some people may be comforted by the idea of a digital afterlife and build their own pre-mortem generative clone that will become a generative ghost, able to preserve their knowledge or cultural or religious heritage – or even participate in the economic system and provide income for their descendants. The bereaved may be comforted, of course. And society could benefit from generative ghosts representing disappearing cultural groups, preserving the wisdom of elders, or educating people about horrors like the Holocaust.

As for risks, Brubaker says, “Addiction is too strong of a term, but you can imagine a kind of desire or escaping into a thing that might simulate a lost loved one.” To that end, bringing in clinical psychologists to participate in this research is essential, he notes. There could also be reputational risks, since a generative ghost could do something to tarnish the memory of the deceased person. Then there are the risks we already experience with AI – hallucinations and fidelity, as well as privacy and security concerns.

While the paper outlines considerations and potential policies for mitigating risks, it also notes that “we do not mean to suggest that there are clear right or wrong approaches for each dimension of our design space.”

“It’s really important to highlight that our paper is not a prediction; if anything, it’s quite far from that,” Brubaker says. “It was us seeing an area of AI that is going to happen, that no one had talked much about yet. Our entire goal was to chart out the landscape so that we could start to piece apart what the different trends might be, what different kinds of research need to happen, and what kind of use cases we may see in the future.”

Does he plan on indulging in this technology himself, creating a pre-mortem generative clone that will become a generative ghost when he dies? “Without a question, without a doubt, absolutely, yes,” he says. “This one is a no-brainer.”