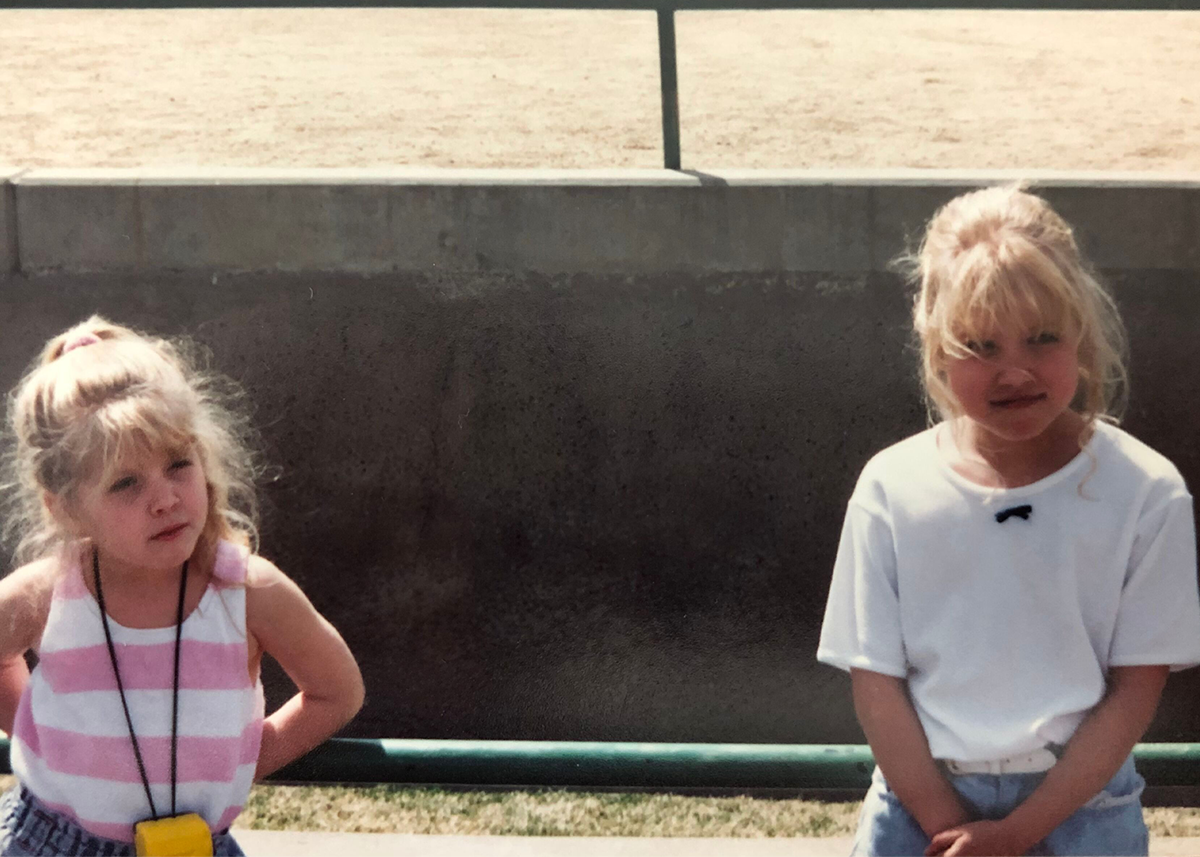

Courtesy of Anonymous Sister

Audio By Carbonatix

Emmy Award-winning filmmaker Jamie Boyle has used her talents as an editor and cinematographer to document underrepresented communities and social justice battles around the country, from reproductive rights in Jackson to the issues faced by the LGBTQ+ community in the limited series Trans in America. But for her directorial debut, Anonymous Sister, she looked to her Denver-area roots. The film examines Boyle’s own family and its collision with the opioid epidemic, which took place while she was growing up as a sixth-generation Coloradan on the Front Range.

In the documentary, Boyle (who is also the film’s cinematographer and editor) deftly weaves her family’s home videos with current family interviews and vintage promotional documents from Purdue Pharma to trace the vast, horrifying sweep of the opioid epidemic – now considered the deadliest disaster in U.S. medical history – as well as the direct effects on her loved ones struggling with addiction. With a gripping personal narrative, the result is one of the strongest Colorado documentaries, a film that will reward subsequent viewings with its beauty, impressionism and nuance.

Anonymous Sister was a big hit on the festival circuit (including at Denver Film Festival 46) and returns to the Sie FilmCenter with Boyle in person on Tuesday, June 20, to coincide with the National Institute on Drug Abuse International Forum this weekend in Denver. Screenings are also presented with addiction resources and training as part of a national impact campaign.

Westword spoke with Boyle to discuss the many layers of her film and the opioid epidemic.

Westword: What’s the story behind the title?

Jamie Boyle: Yeah, it’s funny, I’ve gotten that question a lot, and the answer changes a little every time, because I think I’m still discovering what all it means. … The film was really going to be mostly about my sister; I didn’t set out to tell my entire family’s story. [My sister] Jordan was definitely the most open about her experience, and so it definitely started about her, and because of her twelve-step program. I loved the whole anonymous nature of it, and I was also fascinated by that community and the support they offered one another.

But very quickly, that title evolved to be more about me. I actually had a few people involved in the film say “Oh, I assumed it was about you. You’re always hiding behind the camera; you’re always wanting to be anonymous.” And then I had [someone else] tell me that as a person in a family with substance abuse disorder, they often felt anonymous because everything really has to be singularly focused on that individual and helping them through.

So it’s come to take on a lot of layers, and I love that people are infusing it with their own understandings and what it means to them…and what it really came to mean is what I say in the beginning, which is that I could be anyone. With that said, my family was so privileged and lucky in so many countless ways, but as we’ve seen the nature of this epidemic and others…I think that that title started to feel more and more appropriate, and I liked the idea that it was kind of a stand-in for anyone.

Your parents seem to be pretty enthusiastic videographers. How did the camera come into the household?

People often comment on the fact that we were a fairly low-income family…and yet that had this camera…that was very expensive and not very many people had. My dad managed a feed store in Golden, and the top prize for selling Purina feed was that camera, and his manager gave it to him. He’s also a writer, and he considers it a hobby, but I think he is phenomenally talented in that regard.

So he’s definitely a storyteller, and I took for granted all of these hours and hours and hours of home movies that they had captured…and this film wouldn’t exist, clearly, without it. I think they’re probably 50 percent or more of the film, and they’re the entire heart of it. … The fact that we had these home movies of my sister and I and my whole family’s entire lives allowed me to practically have original footage for a documentary going back decades of their dreams, their loves, their passions, who they were as people before this took hold. And that was just invaluable.

What were your early experiences of falling in love with the camera?

As you’ll see in the film, my sister was singularly focused on figure skating, and it was just not my cup of tea. … I always say my family members were born so artistic and talented – my sister sings like an angel; as I mentioned, my dad writes and my mom has always been able to draw and paint like a master; and I never really had anything like that that fell into my lap and felt easy. But with a camera in my hand, I almost felt like I had my tool, a tool that I could create with that felt very natural to me.

So every time my dad had it out, I always wanted to mimic what he was doing. I was just fascinated by being behind it, and kind of showing the world the way I saw it was always really interesting to me. Then when I was in film school…I discovered the change and truth that could come about and be brought to life because of the camera. Having a camera and interrogating something in the right way, in a specific way – that just blew my world wide open. It was this thing that I had already grown attached to because of what it could do artistically, then finding out at this exact juncture in my life that it could be used to right a wrong was just the perfect storm for what became my life path so far.

When did you know this subject would be a film, and how did you approach your family about that?

Around 2016, my sister got pregnant with her first child and faced all these new hurdles to her sobriety, my mom continued to face a plethora of hurdles, and I really noticed how ill-equipped the medical system at large was to handle what they had on their hands. Not only were prescribing rates at the time barely plateauing, but nobody was ready to handle people who had been through this and come out the other side. It was very, very frightening thinking about them. … I thought, “How is it possible…that we have a health-care system that still doesn’t understand how addictive opiates are? That still doesn’t understand why a drug that’s that addictive, when your tolerance is going up all the time, how that wouldn’t be effective for long-term use? Or how to deal with somebody who has already been through that?”

I was working at the time with [documentary producer Marilyn Ness]…and she was on board from the very beginning. At the same time of dabbling in this, I asked my dad for all our home movies and started transferring those VHS’s and [sourcing] Purdue advertisements from the ’90s – and not just advertisements, but literature and materials that were being sent out to medical schools, to hospital boards, to oversight committees, that didn’t look at all like advertising. … I started inter-cutting them with my home movies, just at night or on weekends, and I quickly realized that I found it really powerful and disturbing. … It was around then I called my sister, and she was really eager to participate, super eager from the beginning, and same with my other family members. I constantly was trying to give them an out or tell them all that it might mean – and I don’t think you can ever prepare somebody to be the center of a documentary, but as much as possible, I really tried to, but they all were pretty adamant (and continued to be) that this is something that they want to be part of and that they’re glad is in this world.

What is the future of the use of these substances? Is it ever going to go away or be safely restrained?

New prescriptions have gone down, [but] we’re still prescribing far more than we should be. We still prescribe 80 percent of the world’s opioids, so it’s still definitely a problem. But it’s mostly a problem when people who’ve been on them, who were put on them long-term for chronic pain before we knew better and are still on them, are either dropped by their doctors, pulled off cold-turkey with no support, and then often fed a lot of misinformation still about who these drugs are good for. So I think the biggest task – and that’s eight to ten million people – is going to be helping those people find alternative pain treatment, because there’s still no evidence still – none, after thirty years – that they’re effective for long-term pain, because your doses will constantly have to go up.

I do have hope that that information is getting out there, and the CDC is constantly coming out with better and better guidelines. At first in 2016, they were accused of really going too hard, of being too harsh, and I think a lot of patients felt no support from their doctors and their health-care systems in trying to get off. They were ripped off quickly, nobody handled it well, and these are the equivalent of heroin – you can’t just drop people overnight. But part of the settlement that happened with the Sacklers a couple weeks ago says that future profits from oxycontin will now go to state governments, which sounds like a good thing, but they now have a financial incentive to have oxy stay on the market and continue to be prescribed. There’s a great article in Reuters about that, and there’s a lot of concerns about that overlap and it not being a good thing.

I tell people just inform yourself, and that if you have loved ones on long-term opioids, there’s a lot of alternatives coming out, and I just encourage people to find some help and support, because it’s out there. It’s just not in the places we’re used to looking, unfortunately.

Anonymous Sister, 6:30 p.m. Tuesday, June 20, at the Sie FilmCenter, 2510 East Colfax Avenue. Tickets are $12, available at denverfilm.org.