Evan Semón

Audio By Carbonatix

In 1933, in the midst of the Depression, Carolina González bought a modest house at 1020 Ninth Street, in one of Denver’s oldest neighborhoods: Auraria.

The house had been built by William Smedley, a Quaker, in 1872, just fourteen years after the town of Auraria was founded by miners who’d panned for gold at the confluence of Cherry Creek and the South Platte River and named their upstart settlement after the Latin word for gold, aurum. Two years later, Auraria merged with the rival town across the creek founded by General William Larimer and became part of Denver.

Auraria started out as a working-class neighborhood of European immigrants, and then, in the 1920s, largely became home to the Latino community. González catered to everyone at her house, which she named Casa Mayan in recognition of her own heritage. She was a nurse and a cook, and she brought her desire to care for others to Casa Mayan. At one point during the ’30s, more than thirty people were living there; she never turned anyone away. After noticing how many children didn’t have adequate clothing and shoes, she established a sewing center so that people could make their own clothing. She eventually opened a restaurant in her family home.

Casa Mayan was soon a gathering place not just for Auraria, but for all of Denver, known for its authentic Mexican food and a friendly atmosphere that welcomed both the elite and the homeless. Notable visitors included Paul Robeson, Henry Ford and even President Harry S. Truman.

Casa Mayan survived tough times, from the Depression through the war years and the 1965 flood, when the South Platte overflowed its banks and inundated much of low-lying Denver. But it could not survive the flood of urban development that was to follow.

In June 1972, fifty years ago this summer, González, along with hundreds of other Auraria residents, received notice that her neighborhood was about to be demolished and she would have to go.

Carolina González ran Casa Mayan for three decades.

Courtesy of Auraria Library Digital Collections

After the 1965 flood, government officials looked over the metro area to determine how such a catastrophe could be avoided in the future. While state and federal agencies focused on building Chatfield Dam, Mayor Tom Currigan looked at the devastation in the Central Platte Valley and pushed for an array of Denver redevelopment projects. “In Response to a Flood,” a city-produced brochure, invited readers to imagine “a beautifully sculpted channel with inviting walkways…new and modern industrial parks throughout the valley. … Picture old Auraria at the confluence of the Platte and Cherry Creek, and a separate village when Denver was founded, transformed into a vibrant urban college.”

Only one of Currigan’s grand plans came to pass: a higher-education campus in the heart of the city. The Auraria Higher Education Center, a new state entity, was created to oversee an educational oasis that would be home to the University of Colorado Denver, the Community College of Denver, and what was then known as Metropolitan State College. But to create the campus, 169 acres of Auraria would have to be swept clean.

The U.S.Department of Housing and Urban Development estimated that the project would cost $24.2 million; the feds would pay $12.6 billion of that, the State of Colorado $5.6 million. Residents of the city of Denver voted to approve close to $6 million in bonds for the rest.

The Auraria Residents Organization fought the plan, as did Chicano activists who were part of a larger movement already sweeping the city. They wanted to preserve what they called the Westside, keeping housing costs low and preserving the character of the area.

The Reverend Peter Garcia of St. Cajetan’s Catholic Church, along with Waldo Benavidez, director of the Auraria Community Center, collected 2,000 signatures on a petition opposing the project. But they could not dissuade Denver’s boosters.

As plans and funding came together, the Denver Urban Renewal Authority displaced 330 households and 250 businesses, many of them moving to neighborhoods north and west of Auraria.

While construction of the campus couldn’t be stopped, a few buildings had the protection of the 1967 Denver Preservation Ordinance, adopted after the Skyline Urban Renewal Project threatened 26 blocks of old buildings in downtown Denver. The Denver Landmark Preservation Commission recommended St. Cajetan’s, built in 1925; the Tivoli Brewery, built in 1870 (and today a student union); and the Emmanuel Shearith Israel Chapel, built in 1876, for landmark designation. Historic Denver, which had formed in 1970 when the Molly Brown House was threatened, revved up again to preserve a slice of the original Auraria neighborhood: a block of old houses on Ninth Street, which were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, the same year Casa Mayan served its last meal.

While the restaurant was gone, as was the family that had lived there, the building was saved.

Construction of the campus was completed in 1976. The fourteen houses preserved on what had become Ninth Street Historic Park, including Casa Mayan, were now owned by the Auraria Higher Education Center, the entity that manages the three institutions.

Carolina González’s grandson, Gregorio Alcaro, celebrates the spirit of Casa Mayan.

Evan Semón

Gregorio Alcaro, 59, remembers when his grandmother, Carolina González, learned she would have to leave Casa Mayan.

She bought a duplex off Federal Boulevard with the money she received for her home; the city also offered her a location in a strip mall for the restaurant. “I remember going down and seeing these places,” recalls Alcaro. “It was not a fast-food Mexican restaurant. That was traumatic.”

It also seemed a slap in the face for the González family, who had created much more than a restaurant at 1020 Ninth Street. Casa Mayan was a melting pot of Colorado and Auraria history, a physical representation of the neighborhood.

“This was the original Auraria higher education center,” Alcaro says. “It was a place where people from all walks of life could come together and learn from each other.” People co-existed; no one assimilated.

“The mission of the Casa Mayan restaurant was a mission of bringing people together across cultural boundaries,” says Jim Walsh, political science professor at the University of Colorado Denver and a longtime friend of Alcaro’s.

In 2006, Alcaro and Trini H. González, Carolina’s granddaughter, founded Auraria Casa Mayan Heritage. Although González hasn’t been part of the nonprofit since 212, Alcaro continues to push to preserve the history of Auraria. He believes in the spirit of Casa Mayan and how it still represents all that Auraria was before displacement. And he also believes that the Auraria Higher Education Center has some promises to keep.

Many former Auraria residents remember being told that AHEC would give scholarships to people who’d lived in Auraria between 1955 and 1973, but nothing was documented. After years of campaigning by the community, in 1994 the schools agreed to offer those scholarships to displaced residents of the Auraria neighborhood, their children and their grandchildren. Between 1998 and 2021, more than 600 people received a displaced-Aurarian scholarship.

The arrangement became more formal on June 8 of this year, when HB22-1393 was signed into law. It acknowledges the displacement of Auraria residents and offers up to $2 million in scholarships to the descendants of those who were displaced to attend any of the three schools on the campus indefinitely.

“I testified before the House, which preserved the scholarship, which prior to this year was an oral history documenting scholarships. Now it’s a piece of legislation,” says Leora Joseph, who was the general counsel and chief administrative officer for AHEC at the time

“It was a place where people from all walks of life could come together and learn from each other.”

On June 14, former residents of Auraria celebrated the new law at the Displaced Aurarians Memory Workshop, part of Museum of Memories, a project of History Colorado that includes storytelling, workshops, art and grassroots efforts to bring to light memories of old buildings and neighborhoods.

“I’m so happy for everybody to help the grandchildren we know to go to school,” said Gregory Gomez, who grew up at 1050 Ninth Street, just three doors down from Casa Mayan. He remembers his mother teaching him to make empanadas, tamales and chile in that house.

Others spoke of life on the Westside, where doors were never locked and kids would play together outside their homes, the smell of lilacs blowing through the Colorado wind.

They remembered Ernie Lopez’s barbershop, a pickle factory, their elementary school and other businesses that used to make up the fabric of the community, including Casa Mayan. They spoke of their past memories as well as a future that would be better because of those scholarships.

But that’s the least of what the schools should do to atone for what the people of Auraria lost, according to Alcaro. “That’s to me the idea that higher education is going to preserve our culture, and it’s not,” he says. “I still feel to this day that they were not compensated justly.”

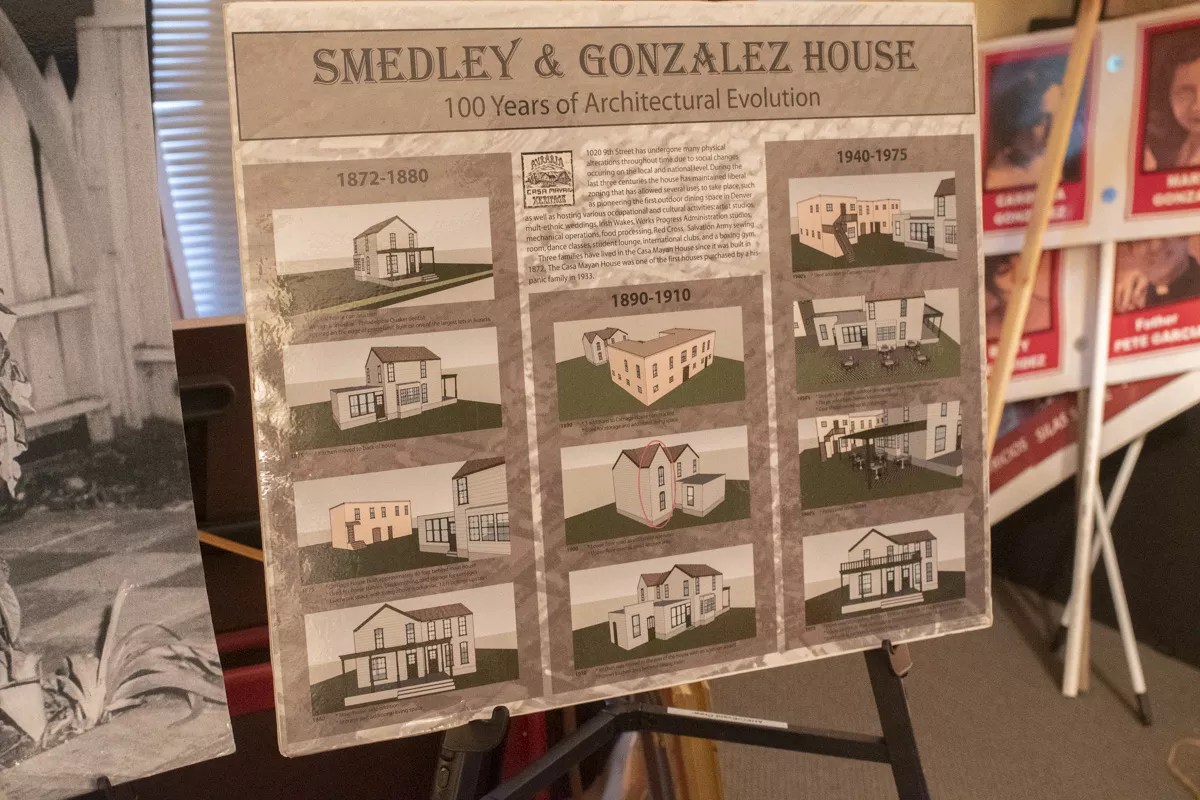

The Smedley/Casa Mayan house through the years.

Evan Semon

Today the Auraria campus is home to Metropolitan State University of Denver, a four-year public institution with 16,396 undergraduate students, 50.3 percent of them people of color. The University of Colorado Denver has 10,200 undergraduate students, half of them people of color. The Community College of Denver has 8,032 students, with 49.3 percent of them Hispanic, African-American or Asian.

The campus has been on a building binge of late, but over the past year, as it prepared to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the displacement, officials became more involved in preserving the history of the neighborhood and helping its former residents. Putting the scholarship promise into law was just the start.

Both AHEC and the University of Colorado Denver have been looking at the Ninth Street buildings they oversee and considering how they can be worked back into the community.

In March, the University of Colorado Denver revealed plans to restore and renovate all of the buildings on Ninth Street that the school occupies. University of Colorado Denver regent Nolbert Chavez is leading that project, starting with 1050 Ninth Street.

Chavez will be working with Rita Gomez, a former resident, on the renovation, refurbishing the structure while staying true to historic materials and styles. The building currently houses part of the school’s English department, as do 1051, 1059 and 1061 Ninth Street; the department’s main offices are in 1015 Ninth Street. The University of Colorado Denver Honors and Leadership Program is located at 1047 Ninth Street.

The 1050 Ninth Street project has been estimated at $400,000 and has a deadline of next spring, according to Chavez. “We’ve raised enough to do the first house; we’re moving forward with that starting this fall,” he says. “After that house is done, we’re going to invite community and funders and students and others to see what’s possible, and that’s when the larger fundraising activities will begin.”

Ultimately, he hopes the six houses that the University of Colorado Denver oversees are “active and student-facing,” serving the entire community. One could even be a Latino research center, a place that is not directly connected to the campus or students but helps preserve history, Chavez says.

While physical preservation projects are in the works, so is a digital effort.

An exhibit inside Casa Mayan includes González family memorabilia.

Evan Semón

Brian Page, associate professor and chair of Geography and Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Denver, is working on a project to digitize the history of Auraria by creating interactive maps that show how the area has changed. With funding from the school’s City Center, Page is putting together GIS maps to show what it looked like through the decades, before and after displacement. “I’m working with some of the members of the displaced community to use these digital re-creations to provide frameworks, story maps that can support their storytelling,” Page says.

Through the maps, people will be able to walk digitally through different points in time, entering buildings and finding information on them. “This is an urban renewal campus; it targeted this district for removal in order to create the space for a higher education center,” Page notes. “Yet…once that process was completed, there’s not very much evidence on the ground. Even though there are remnants of the historic spaces that have been saved, there’s not a lot to tell you about what used to be here and what it was like.”

Like the University of Colorado Denver, AHEC is committed to commemorating the past. “We want to continue that historical focus to learn a lot about who lived here, where they are now, and what their connection is now, so we’re really open to listening to all the voices,” Joseph says. The challenge is to combine historical preservation with educational use.

Alcaro doesn’t believe the preservation work makes up for the area’s inaccessibility. “I have no access” to his family’s former home, he says. “It’s very oppressive.”

“There are different voices within that community that I think want to represent the community at large and want to be the partner that AHEC sits down at the table with, and I think what AHEC’s challenge is today is to very clearly ensure that all voices in the displaced community are at the table, including Gregorio,” notes Walsh.

AHEC Campus Planning is housed at 1056 Ninth Street, 1067 hosts AHEC’s executive office, and 1027 is home to AHEC’s marketing and communications efforts. The Casa Mayan building is managed by the Auraria Events team and falls under the purview of AHEC. Anyone can go in the house; “they just need to go through the procedures,” Joseph says. Although it’s currently used for special events, AHEC is looking for suggestions for its future use.

“We want community input.We’re not going to drive what the goal of the house is.”

“We want community input,” Joseph says. “We’re not going to drive what the goal of the house is. … We are working to look to hire somebody as an internal employee to help us deal with honoring Ninth Street and really celebrating it and making sure we have the appropriate, specifically Latina and Hispanic, partners to really bring that culture at the forefront to our campus.”

But Alcaro thinks the house shouldn’t only fall under AHEC. “This house needs to be given to a management of people who are non-partisan,” he says. “They treat all the colleges and the students equally. We can’t be competing and deciding what is historical. That’s why our [Auraria Casa Mayan Heritage] proposal has been, and was, an agreement that we were institutional partners. We, the descendants of Casa Mayan, would like the same opportunity to manage the space of an incredibly important institution in Colorado history.”

Auraria has a model that could work for Casa Mayan: the success of the Golda Meir House, at 1146 Ninth Street. It was moved there in 1988 from 1606-1608 Julian Street, where Golda Meir lived for a while before she grew up to become the first female prime minister of Israel.

“It was put here in the ’80s, and we have really focused on a rededication,” says Joseph. “We’re having a big conference here this summer, a gala eventually to really think about the themes of that house – which are women’s leadership, education and immigration. It’s been so wildly successful, and we really just want to copy the success of that project with potentially an executive director of Casa Mayan.”

On August 1, the Golda Meir House will host “The Only Woman in the Room,” a symposium at which authors, women’s studies experts and museum professionals will discuss Golda Meir’s life. In the process, they’ll suggest future directions for the building.

Alcaro would like to see a similar situation at Casa Mayan, perhaps a museum like the Molly Brown House that’s dedicated to its former occupant.

Community members gathered at Casa Mayan on July 23.

Evan Semón

On July 23, 1020 Ninth Street celebrated its 150th anniversary. Alcaro and Lucha Martinez de Luna, associate curator of Hispanic, Chicano, Latino History and Culture at History Colorado, hosted a screening of the documentary Casa Mayan and a discussion afterward that touched on documenting the history of other houses on Ninth Street, too.

History Colorado and the AHEC events team organized the event, and for the first time in many months, the house was full of people. Artifacts and informational materials lined the walls, sharing the story of Casa Mayan and Auraria. Alcaro added to the stories with his own memories and tales of his grandmother and other relatives.

Beyond the day’s displays, though, Casa Mayan is in a state of limbo. The three upstairs bedrooms are filled with papers, desks, cleaning supplies, boxes and other random items; downstairs are photos of former Hispanic legislators that were part of an old exhibit. According to Walsh, the randomness of the rooms’ contents shows just how undecided the community is about the house. “There’s never been a consensus on how we can move forward in the interior of this house and how everyone [can] feel respected and included,” he says.

Walsh has held classes in the large conference room downstairs; he says that the setting has enriched students’ experiences.

But he’d like to see the building’s contents truly acknowledge its past and the legacy of the woman who lived here. Carolina González was inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame in 2020, and her welcoming spirit should be commemorated.

“Carolina González was the visionary. She understood that bringing people from all cultures together is what the restaurant should be about, and that’s what she did,” Walsh says. “A re-envisioning of Casa Mayan is embracing that spirit, is everyone working together to preserve that spirit. I am confident that at the end of the day, the Casa Mayan mission and spirit will persevere.”