Kristen Fiore

Audio By Carbonatix

As the Molly Brown House Museum put the finishing touches on its new Titanic exhibit, it found itself on a collision course. Not with an iceberg, but with a large, immersive Titanic experience washing up in the Mile High City.

Such an out-of-state commercial extravaganza coming here might seem like a slap to those who support the Molly Brown House and the woman who lived at 1340 Pennsylvania Street over a century ago: Margaret (never Molly) Brown, who became a national heroine after the Titanic tragedy. But those who run the facility are looking on the bright side.

“I think they’re great companion experiences, so I would recommend doing both,” Andrea Malcomb, museum director and vice president of Historic Denver, offers diplomatically.

Titanic: An Immersive Voyage opened at Exhibition Hub Art Center Denver in May (yes, we reviewed it) and dates were recently extended through September 21. The installation features 3D videos and immersive galleries that allow participants to walk through the Titanic’s construction to its fatal end 2.5 miles beneath the sea. The announcement of the installation’s imminent arrival acknowledged Brown’s Colorado connection, noting that “her legacy is enshrined in the Molly Brown House Museum, her restored Denver residence, which stands as a testament to her enduring impact on the community.”

China and silverware from the Titanic’s sister ship, the Olympic. “The Olympic went on until it was decommissioned after World War II, so lots more exists of it because it’s not at the bottom of the ocean,” Malcomb says.

Kristen Fiore

The museum’s See Justice Done: The Legacy of the Titanic Survivors’ Committee, which also opened this spring, offers a more intimate look at the aftermath of the April 15, 1912, tragedy that killed an estimated 1,500 people, honing in on Denver socialite, suffragette and philanthropist Margaret Brown and how she got the moniker “Heroine of the Titanic.” The exhibit includes several newly acquired artifacts that tell the story of Brown’s role in forming and leading the Titanic Survivors’ Committee and helping those pulled to safety on the Carpathia – particularly the immigrants and Titanic crew members who lost everything with the sinking of the “Unsinkable Ship.”

The artifacts include a letter Brown wrote to her daughter, Helen, days after the sinking of the Titanic that recounted the harrowing events, a commemorative flag with an embroidered emblem thanking Brown on behalf of the surviving members of the Titanic crew, and a ushabti talisman.

Around the time of the Titanic, Brown was hobnobbing in Newport, Rhode Island, and traveling the globe. In 1912, she and her daughter vacationed in Egypt, then France, where Brown learned her grandson was ill. Helen hung back in Paris, but Brown immediately booked passage back to the U.S. on the Titanic. During her journey, she kept a souvenir that she had picked up in Egypt – the ushabti – in her pocket.

The Ushabti Molly Brown kept in her pocket during the sinking of the Titanic.

Kristen Fiore

“Ushabtis were little funerary statues, and on the street you could buy a souvenir or a replica of it,” explains curator of collections Stephanie McGuire. “She did in 1912, right before she boarded the Titanic, and it stayed in her pocket through the journey. She thought of it as her good luck charm and ended up gifting it to the captain of the Carpathia, Captain Rostron, as a thank you for helping the survivors.” Rostron’s family held onto that good luck charm, but lent it to the museum for a year for this exhibit.

After the Carpathia reached New York, Brown stayed in the city for a few days to give interviews from the Ritz Carlton Hotel and do some shopping since she now had no clothes. “Then she heads straight to Denver because she wants to catch up with her son Larry and see if his baby is sick or not, and it turns out he’s fine,” Malcomb says. “We’ll have a telegram on exhibit that Margaret received when she was on the Carpathia from Larry saying, ‘Thank goodness you’re well, mother.'”

Upon returning to Denver, Brown stayed in a suite of rooms at the Brown Palace (built in 1892 by Henry Brown, no relation) because she’d rented out her home. At the hotel, she gave several press interviews and wrote the letter to Helen on Brown Place stationery; the museum later acquired it from the estate of a Brown relative. “She was immediately called the Heroine of the Titanic,” Malcomb recalls. “It happened almost instantly. Within days of the disaster, newspapers are calling her the heroine, and that letter’s great, because she’s saying, ‘I must have my head examined, they’re calling me the Heroine of the Titanic.'”

Textile conservationist Paulette Reading and curator of collections Stephanie McGuire hold up the commemorative flag that Reading worked to restore before the museum put it on display for See Justice Done.

Kristen Fiore

The flag was given to the museum by a private donor. “It’s not from the Titanic, but it’s probably a handmade commemorative piece to look like a White Star Line flag,” McGuire says. “It has this patch on it that says, ‘From the crew survivors to Mrs. J.J. Brown.’ It’s a little bit of a mystery because none of us have ever heard of it. There hasn’t been any evidence of a ceremony that was publicized in newspapers, it’s not in any of the family letters or accounts, but the fabric is from the period and as you’re looking at this letter of hers, she’s talking about all these ways that people were thanking her for what she did on the Carpathia, which was starting the Titanic Survivors’ Committee.”

A letter written by Margaret Brown on Brown Palace paper to her daughter recounting the events of the Titanic’s end.

Kristen Fiore

And that helped inspire the exhibit, which recently gained a new artifact: a Titanic letter written by survivor Archibald Gracie is also on display. “It is a fine ship but I shall await my journey’s end before I pass judgment on her,” Gracie wrote forebodingly.

According to Malcomb, See Justice Done should help people understand that the Titanic wasn’t a ship only for wealthy, first-class travelers. “It was also an immigrant ship,” she says. “People coming from all over the world to the United States, and those are the people Margaret wanted to help the most in the aftermath of the disaster, understanding that their new lives were shattered before they even started. And she wanted to help the crew as well.”

“I hope that people walk away feeling like one woman did something,” McGuire adds. “One woman took it upon herself to make a change when no one else was really taking action, and she was actually able to make a difference, and the difference is shown in the artifacts that are on display.”

Malcomb hopes the exhibit inspires people to think about what they can do to help their community. Brown certainly did when she moved down from Leadville, where she and her husband made their fortune. At the same time she was trying to win a place in society, she also helped the less fortunate, pushing for public bathhouses and a woman’s right to vote.

She left a legacy of action that was resurrected in 1970, when the home where Brown had lived was threatened by the wrecking ball. The movement to save it gave rise to Historic Denver.

At the time, the building was owned by Art Leisenring, who ran it as a boardinghouse; other old mansions in Capitol Hill and downtown were being scraped for urban renewal and turned into parking lots.

“Art wanted to move on but knew this house had a great history and something to offer to the citizens of Denver,” Malcomb says.”He reached out to people who he knew also cared about the city and its history and by December of 1970, they convened and created a nonprofit called Historic Denver, with the first goal to take over the house and open the doors to the public as a museum.”

When the museum’s doors opened in March 1971, the building still looked like a boarding house. But then the restoration effort got a major boost from Larry Brown’s estate. “Larry left everything to the Colorado Historical Society (now History Colorado) with the caveat that it not be opened for 25 years. He died in late 1949. It was 1975 before they were able to unseal all those archives. And when they did, he kept everything,” Malcomb says. “Photos, letters, gas receipts – you name it. Those photos became invaluable and really sped up the restoration process because it wasn’t just a guess, it was actually using photographic evidence.”

Margaret Brown honored after her her efforts to help the immigrant and Titanic crew survivors.

Molly Brown House Museum

Malcomb credits The Unsinkable Molly Brown, a 1960 Broadway musical made into a movie with Debbie Reynolds in 1964, with helping the salvage operation, too. “The play is what brought people to this house, it’s what saved this house,” she says. “Denver and the country were obsessed with the story and wanted to know the real story, but no sources had really been found yet besides some newspaper articles.” That helped Hollywood create the myth of “Molly Brown,” but over the years, the museum has been able to set the story straight.

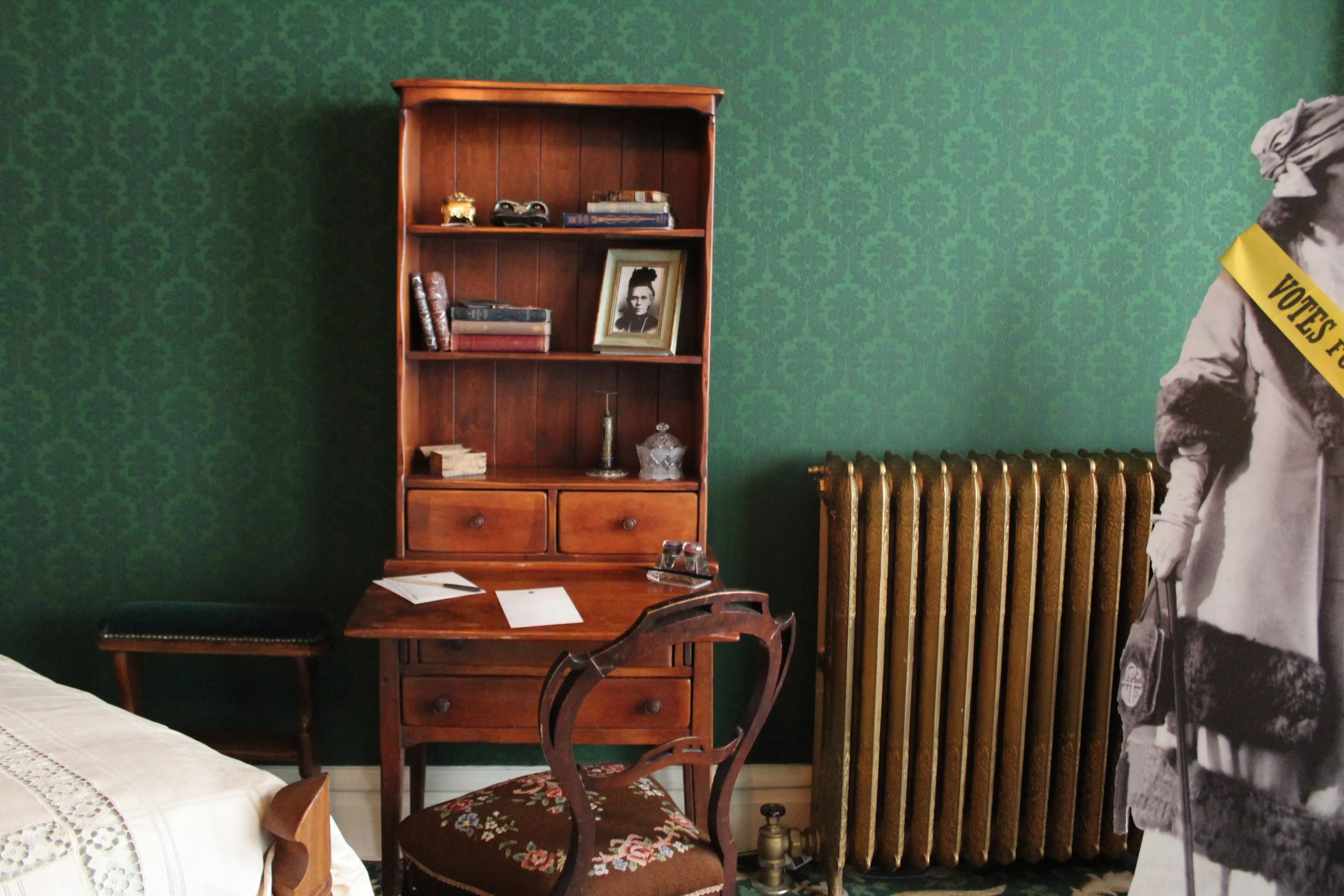

Decades later, Brown’s possessions are still finding their way back to the house, including this secretary desk Brown used later in life.

Kristen Fiore

While the Molly Brown House Museum isn’t a huge warehouse equipped with virtual reality and other high-tech elements designed to make visitors feel like they’re on a sinking ship, the house has its own immersive qualities, according to Malcomb. “We are stepping into what feels like an authentic past where you’re stepping into Mrs. Brown’s home, hearing her story and hopefully being inspired by it,” she says. “You’re seeing artifacts from material culture from that time. The ushabti that was in her pocket, the flag that was given to her, the letter she wrote. Through these artifacts, you’re able to experience 1912.”

While technological tricks can engage people in history, the museum’s physical surroundings do, too, she adds: “In our house, I love the sounds because it’s the creaking door, it’s the talking people, it’s like you can almost hear Mrs. Brown’s skirts rustling as she’s going around the corner.”

See Justice Done: The Legacy of the Titanic Survivors’ Committee was recently extended through December 28 at the Molly Brown House Museum, 1340 Pennsylvania Street. Find more information at mollybrown.org.