Tim Gabor

Audio By Carbonatix

TRANCE PARTY

It was a long time ago, almost seventy years back. Not many people still in this world can recall with confidence what they were doing on December 31, 1952.

But Joe Bullen remembers. That New Year’s Eve, his friend Morey Bernstein threw a party. It was one of the most memorable parties of Bullen’s life.

Bullen and Bernstein were young, up-and-coming captains of industry. They had graduated from Pueblo’s Centennial High School a few years apart, each at the top of his class. After college they’d moved into management positions in thriving family businesses. The Bullen Bridge Company built dozens of steel bridges across southern Colorado before evolving into a concrete company. Bernstein Brothers was a heavy-equipment supplier with a national clientele. Both men were pragmatic, hard-driving executives, with zero interest in metaphysical mysteries or cosmic hoo-ha.

Or so Bullen thought, right up until that night. Shortly after he and his wife, Betty, arrived at Bernstein’s place, they were intercepted by their host.

“He told us, ‘Forget about the party upstairs – go down to the basement,'” Bullen recalls. “He had a recording he wanted us to hear.”

Bernstein soon joined the couple downstairs and switched on a reel-to-reel tape machine. The lulling voice of a hypnotist could be heard, urging someone to fall “deeper and deeper asleep.” The hypnotist was Bernstein. The subject was 29-year-old Virginia Tighe, known as Ginni to her friends. Bullen knew her husband, a local Oldsmobile dealer.

Hypnosis had been Bernstein’s hobby for years; he’d treated people for stuttering, migraines, insomnia and other afflictions, without charge. Lately he’d been experimenting with age regression, urging his subjects to “turn back through time and space, just like turning back the pages in a book,” and recall long-buried childhood memories. On the recording, Bernstein asked Ginni questions about her life when she was seven years old, then age five, then three. Her voice grew fainter and more childlike as she named friends and toys she had at different ages, back to a “cotton dolly” she had when she was one year old.

Then the experiment took an even weirder turn. “I want you to keep on going back and back and back in your mind,” Bernstein said on the recording. “And surprising as it may seem, strange as it may seem, you will find that there are other scenes in your memory. There are other scenes from faraway lands and distant places. … Now you’re going to tell me what scenes came into your mind. What did you see?”

“Uh…scratched the paint off all my bed,” Ginni replied, her voice still small. “It was a metal bed, and I scratched the paint off it…got an awful spanking.”

“What is your name?” Bernstein asked.

“Uh…Friday.”

“Don’t you have any other name?”

“Friday Murphy.”

As the session continued, Ginni corrected the pronunciation of her name: It was not Friday, but Bridey, short for Bridget. She was four years old. She lived in Cork, Ireland, with her parents and an older brother, Duncan. A younger brother had died as a baby. She wasn’t good with dates, but then Bernstein took her to the age of eight and asked her what year it was.

“Eighteen something,” she said. “Eighteen oh…eighteen-oh-six.”

“Eighteen hundred and six?”

“Uh-huh.”

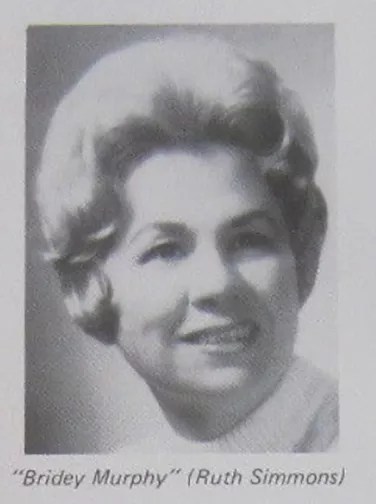

Under hypnosis, Virginia Tighe described a past life in Ireland; her account became a media sensation.

Wikipedia/Doubleday

In a voice that began to take on subtle traces of an Irish brogue, “Bridey” provided numerous details regarding her bleak existence: a Protestant childhood in Cork; then a move to Belfast with her husband, a Catholic barrister; her death from a fall down the stairs in 1864, at the age of 66. In response to Bernstein’s questions, she also made enigmatic references to encountering the spirit of her infant brother in a ghostlike afterlife and to another brief life, prior to her time in Ireland, in a place called New Amsterdam.

The tape ended with Bernstein waking up his subject. Bullen was fascinated. The entire account sounded plausible, matter-of-fact, more like a genuine memory than some melodramatic, scripted performance. But if it was real, that meant there really was something to this reincarnation business that the Hindus, the Buddhists and others had been talking about for centuries.

“It was contrary to many of my beliefs,” says Bullen, who was raised as a Presbyterian. “And it changed almost instantly some of my beliefs.”

Over the next several months, the Bullens sat in on additional recording sessions with a hypnotized Ginni Tighe, helping to devise questions that might aid in confirming her story; there were six sessions in all. Although Bernstein took steps to protect Ginni’s identity, rumors about a local housewife recalling her previous life in nineteenth-century Ireland soon became the talk of Pueblo. In 1954 the Denver Post published a three-part series in Empire, its Sunday magazine, on the Bridey Murphy phenomenon, and the story quickly went national.

The series was followed by Bernstein’s own account of his “experiments,” The Search for Bridey Murphy. The book rocketed to the top of the bestseller list in early 1956 and stayed there for months. It sold hundreds of thousands of copies – and, after the release of a cheap paperback, millions of copies – and was translated into dozens of languages; Paramount bought the screen rights and rushed out a potboiler starring Teresa Wright. Bernstein had tapped into something wild and dissonant in the staid 1950s zeitgeist: a rabid public interest in the paranormal, from UFOs and ESP to clairvoyance, poltergeists and past-life regression. The book “is apparently being purchased by thousands who do not normally buy books,” Life magazine reported. “They are interested not only in the possibility of a life beyond the grave but of one before the obstetrical ward.”

The media firestorm in response to Bernstein’s book was formidable. Prominent members of the psychology community warned of the dangers of amateur hypnosis, kickstarting the modern skepticism movement and its attacks on pseudoscience. Evangelical leaders denounced Bridey from the pulpit, regarding the claims about rebirth and the afterlife as an assault on Christian doctrine. Tabloid journalists set out to debunk the story; the Post, which had started the ball rolling, sent one of its most popular reporters to Ireland in an effort to prove that the details of Bridey’s life were accurate.

“Turn back through time and space, just like turning back the pages of a book.”

Both the debunking and the Post‘s investigation left a lot of questions unanswered. For years, Bernstein passionately defended the integrity of his work, threatening legal action against those who insinuated that he’d rigged the sessions. But it was Ginni Tighe, who’d never sought acclaim or fortune, who took the brunt of the jokes and accusations.

“Bridey cost me a lot of sleepless nights,” she told one reporter, years after the frenzy over the book had dissipated. “Probably the main reason I’ve kept my cool is that I’m not convinced I was Bridey Murphy or anyone else.”

Bernstein and his subject both passed away in the 1990s. The real story behind their astral journey can be found in a metal file cabinet at the Pueblo County Historical Society, the repository of Bernstein’s papers dealing with the Bridey Murphy experiments. Amid the voluminous correspondence, the original tapes of the sessions, the piles of newspaper clippings and letters from strangers describing their own past-life experiences are some hints about what was really going on in those trances. It’s a strange story, more poignant than Bridey’s own tale: the story of two people engaged in an earnest exploration of the subconscious that got out of hand.

Most people in 21st-century Colorado have never heard of Bridey Murphy. But Joe Bullen remembers. He’s 94 years old now. He and his wife are the last surviving witnesses to what took place, and he has no trouble vouching for the sincerity of the people involved.

“I think the experiment was valid and honest,” he says. “Whatever the explanation is, it was not any kind of a hoax.”

THE DAZE OF HER LIVES

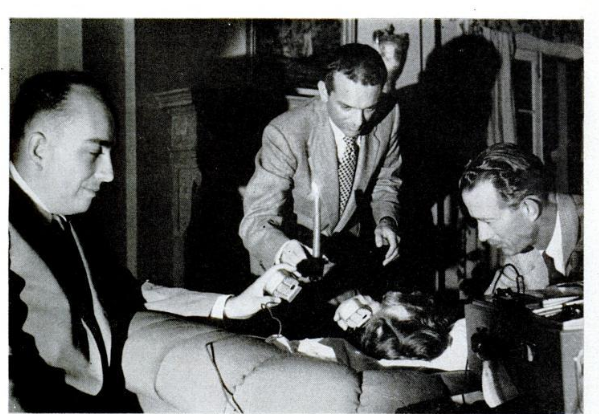

In a publicity photo, Morey Bernstein (center) re-enacts putting Ginni Tighe in a trance using a candle; Joe Bullen (left) was one of the witnesses who helped record the sessions.

Pueblo County Historical Society

People who knew Morey Bernstein describe him as a brilliant businessman and a serious thinker. Until he began his paranormal experiments, he was also an atheist who scoffed at the notion of an afterlife (or a pre-life). He was too busy for such folderol.

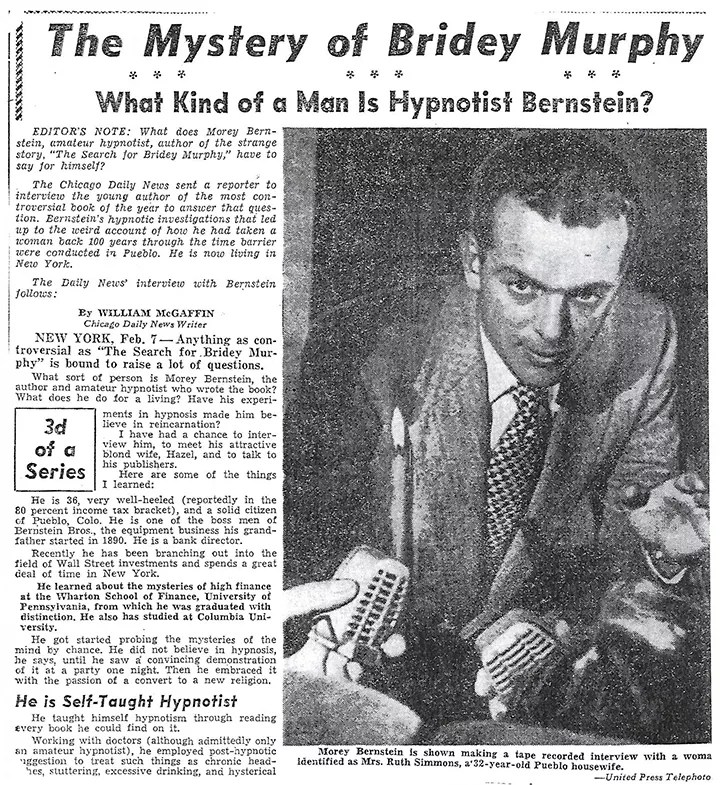

Bernstein Brothers began as a junkyard, started by Morey’s grandfather, a Russian immigrant, in 1890. Over generations, the operation expanded into providing heavy equipment to industrial, farm, mining and construction businesses, everything from concrete mixers to oil tanks. Armed with a business degree from the Wharton School, Morey proved to be an innovator, patenting a version of snap-together fencing and buying military-surplus Jeep engines and putting them into tractors that sold for $500. By the time he met Ginni Tighe, his company was listed under 47 product categories in the Pueblo phone book, and 32-year-old Morey served on the board of directors of three companies and a bank.

But Bernstein wasn’t all that interested in the family business. He called it Ulcers, Incorporated. His obsession was hypnotism.

Nearly a decade earlier, he’d seen a hypnotist put a woman in a trance at a party; skeptical at first, he started reading everything he could find on the topic and pondering its practical applications. The first person he hypnotized was his wife, Hazel, who proved to be a good subject.

In his book, Bernstein describes his “gratifying experiences” using hypnotism to help people stop smoking or shake other bad habits. But it seems likely he also had personal reasons for exploring the mesmeric arts. When he was in high school, some jokers had thrown him into a lake, misjudging the shallowness of the water. Bernstein broke his neck. He endured months of arduous rehabilitation and continued to suffer from health issues, from a bad back to what a colleague called “congenital metabolism problems,” for much of his life.

Bernstein was intrigued by hypnotism’s potential for controlling pain, and he was bitterly disappointed to discover that he was incapable of being hypnotized himself. (Researchers estimate that 25 percent of the population can’t be hypnotized.) He tried a pressurized oxygen chamber, an injection of sodium pentothal (“truth serum”) and even electroshock therapy in an effort to improve his susceptibility. Nothing helped.

Convinced that hypnotism could unlock hidden resources in the mind, Bernstein conducted tests to try to prove that a subject’s extrasensory perception – ESP – could be enhanced in a trance state. He read widely in paranormal literature and was particularly taken with the life of Edgar Cayce, whose career as a psychic healer and prophet began with hypnotic treatments for laryngitis. That, in turn, led Bernstein to the frontiers of age regression and reincarnation; if only he could find the right subject, he mused, he might be able to uncover past lives.

He found that subject in Ginni Tighe. Bernstein didn’t know the Tighes well, but they traveled in the same social circles he did, and Ginni had agreed to let Bernstein hypnotize her twice before, hoping it would help with her allergies. Bernstein regarded her as a “true somnambulist” – she achieved a deep trance state and remembered nothing about the experience when awakened. It took months for Bernstein to persuade Ginni and her husband, Hugh, to make time for another “experiment” on their crowded calendar, a whirl of cocktail parties, bridge games and club dances.

The couple finally agreed to visit Bernstein’s place on a Saturday evening, November 29, 1952. Bernstein had Ginni lie on a couch and focus on a candle flame while he guided her into a trance. The session produced the recording that Bullen heard four weeks later, on New Year’s Eve: the debut of Bridey Murphy.

“Whatever the explanation is, it was not any kind of a hoax.”

To Bernstein, the evening was a revelation. While it wasn’t definitive proof of reincarnation, he didn’t know how else to explain such vivid recall of a time and place the subject had never encountered. He was eager to schedule more sessions. But the Tighes were ambivalent. They didn’t know if reincarnation was real or not, but they each had religious relatives who would be deeply offended by the idea. Hugh didn’t like his wife being hypnotized, and insisted that further sessions be kept under an hour.

In 1953 letters to Bernstein, Ginni referred to him affectionately as “Svengali” and confessed she didn’t know how to spell Bridey’s name. She wrote that she didn’t want the tapes used for “public consumption” and expressed concerns for her privacy. She didn’t know much about what was on the tapes – which was fine with Bernstein, who didn’t want to “contaminate” future sessions – but assured him she wasn’t just regurgitating something she’d read: “I definitely have not read anything regarding Ireland and Irish history.” She didn’t own an encyclopedia or even a library card, she added.

Morey Bernstein made millions in heavy equipment, but his obsession was hypnotism.

Denver Public Library Western History Collection

In the subsequent hypnosis sessions, stretching over ten months, Bridey patiently responded to dozens of questions designed to nail down her story. She described a trip to Antrim with her husband, Sean Brian Joseph MacCarthy, a barrister who wrote articles for the Belfast News Letter and taught law at Queen’s University. She named shops she frequented, a school she attended, the parish priest who presided at her wedding, the white frame house in which she lived. She fielded queries about meals she prepared, as well as local crops, customs and currency. She faltered when asked to provide some Gaelic words, insisting that Gaelic was “for the tongues of the peasants,” but she seemed familiar with the Irish legends concerning Deirdre of the Sorrows and the warrior Cuchulain.

The sessions provided a wealth of claims to be analyzed and verified. Surprisingly, though, almost no fact-checking occurred before Bernstein embarked on a book about the sessions; he said his editors told him that it would be more credible if they arranged for an “independent” inquiry once the manuscript was in hand. But then the Bridey Murphy story broke in the Denver Post. The exclusive Sunday series wasn’t so much a scoop as it was a carefully orchestrated PR campaign, with Bernstein at the podium.

The author of the series, William J. Barker, was a folksy editor, columnist and longtime talk-radio host on KOA. His brother-in-law also happened to be a neighbor and friend of Morey Bernstein’s. Barker was convinced that the recordings were dynamite; any hesitation he might have had vanished after Bernstein hypnotized Barker’s wife and had her recalling a scene from a past life, one that involved soldiers in “country clothes” carrying a flag with stars in a circle, apparently a reference to the American flag in the period right after the Revolutionary War.

The arrangement between Bernstein and the Post was a peculiar one, even by the slipshod journalistic standards of the time. The newspaper agreed to use a pseudonym for Ginni Tighe, calling her “Ruth Simmons” (the same alias Bernstein would use in his book). Bernstein was allowed to read the story before publication and change details he didn’t want in there. “Ruth” wasn’t interviewed at all. It was the beginning of a long-running collaboration between Bernstein and Barker, in which the scribe would serve as the hypnotist’s chief defender and flack.

The series generated dozens of letters and phone calls. Some condemned the stories as sacrilege, others offered their own enthusiastic accounts of reincarnation. Barker wrote a follow-up piece, assuring readers that the second half of Bernstein’s much-anticipated book would “contain the findings of impartial researchers in Ireland hired to check on Mrs. S’s every statement through old records, maps, newspapers, libraries, houses, towns and graveyards.”

Yet when the book came out, The Search for Bridey Murphy featured no such vetting. Doubleday had bought the book from a smaller publishing house, anticipating a hit, and did only cursory fact-checking. A few pages in the final chapter confirmed that the Belfast News Letter, Queen’s University and other obvious reference points did exist; but the book offered no proof that Bridey, her husband or other principal figures in the tale had ever walked the Auld Sod.

None of that seemed to matter to the book-buying public. Joe Bullen went to a convention in Chicago not long after the book was released. He remembers seeing displays of The Search for Bridey Murphy dominating one large bookstore – not just a single table, but eight, ten. Stacks and stacks of books, feeding an ancient hunger. Bernstein was also hawking LP recordings of the first session, the one Bullen had listened to in the hypnotist’s basement just three years earlier.

This was going to be big, Bullen realized. Really big.

GETTIN’ JIGGY WIT IT

In the third hypnosis session, Ginni described a dance, one that Bridey had learned as a child, called the Morning Jig. Bernstein gave her a post-hypnotic suggestion, commanding her to remember the jig, then brought her out of her trance. At his prompting, Ginni performed a nimble dance that ended with putting a hand to her mouth, as if suppressing a just-woke-up yawn.

By the summer of 1956, a sizable hunk of America was dancing to Bridey’s tune. Pop songs celebrating the ghostly redhead, including “The Love of Bridey Murphy” (by Billy Devroe’s Devilaries), hit the airwaves. Chic bars offered a reincarnation cocktail. Smart Denver hostesses held “Come as you were” parties. Birth announcements urged friends and family to “welcome back” the new arrival.

Many people assumed that Bridey’s alter ego was cashing in on all the fuss, but that wasn’t the case. The Tighes never sought compensation for Ginni’s role in Bernstein’s research. Bernstein insisted that the couple should share in his earnings, to avoid hard feelings down the line. But the actual share he offered was modest to the point of exploitation: 5 percent of Bernstein’s take. As the book sales mounted – by mid-March, more than 200,000 copies were in print – Bernstein made hundreds of thousands of dollars in royalties; the Tighes got checks for a couple thousand here, a couple thousand there. Bernstein collected $50,000 from the sale of the movie rights; a mere $2,500 went to Ginni Tighe, whose life story (life stories?) was being adapted for the silver screen.

Paramount rushed out a movie version of Bridey’s story; it flopped.

Courtesy Everett Collection

The money didn’t seem to matter much to Bernstein, who was already wealthy from his family business. But it was a poor bargain for Ginni, who found her cherished privacy dwindling rapidly. The book had been out only a few weeks when Time revealed the true identity of “Ruth Simmons.”

Ginni’s phone blew up with calls from kooks and reporters. She was deluged with letters seeking spiritual guidance or offering it, including some simply addressed to “Bridey Murphy, Pueblo, Colorado.” Rubberneckers drove by her house, honking and gawking. There were unannounced visits from preachers who wanted to save her from heresy and hellfire. She was invited to appear on national television shows – including her favorite, George Gobel’s variety show. A Hollywood agent said he’d pay her $15,000 just to sit at a table in a nightclub every night for a week.

She turned down all the offers. Some of the fallout, though, was hard to avoid. A teenager who committed suicide in Shawnee, Oklahoma, left behind a note: “I am curious about the Bridey Murphy story, so I’m going to investigate the theory in person.” His mother sent a clipping about the death to Ginni with a note, asking if she was proud of herself.

Journalists, including a Chicago Daily News reporter and a Life correspondent, began their own searches for Bridey Murphy. Checks of city directories, birth and marriage and death records turned up no trace of her in Cork or Belfast. No trace of a barrister named Sean Brian Joseph MacCarthy, either, or Bridey’s father or father-in-law, who were also supposed to have been barristers. Her husband’s Catholic church and priest, her school, her favorite book, even the street she lived on (Dooley Road) didn’t seem to exist. And many other details just didn’t sound right. Metal beds were extremely uncommon in Ireland in the early 1800s, as were houses built of wood. She knew some of the stories about Cuchulain but called him “Cooch-a-lane,” and called Sean “See-an” and a lyre a “leer,” in defiance of common Irish pronunciation of those words.

Bill Barker of the Post jumped to the book’s defense. (“Frankly,” he wrote to Bernstein, “we consider Bridey an Empire baby, and feel she should be pushed in the pages where she first was publicized.”) His editors dispatched him to Ireland for three weeks, and he produced an exhaustive – and exhausting – 19,000-word rebuttal for the Sunday magazine, a bizarre blend of empirical inquiry and chatty disputation.

Barker pointed out that many vital statistics in Ireland weren’t kept before 1864 or were destroyed – thus the lack of any mention of Bridey in the available public records proved nothing. He theorized that the saucy colleen had exaggerated the importance of her family and that her husband was really a clerk, not a barrister. No Dooley Road, okay, but an 1801 map of Cork showed an area called Mardike Meadows, and Bridey had said she’d lived at “The Meadows” as a child.

Much of Barker’s piece touted the obscure facts that he could verify. She’d named a greengrocer called Carrigan and a place she bought “foodstuffs” called Farr’s; both had operated in Belfast at that time, along with businesses that seemed to match the “big rope factory” and “tobacco house” she mentioned. Her description of the Glens of Antrim was accurate, and there were several hard-to-find-but-genuine geographical reference points she included in recounting her trip from Cork to Belfast – even though the route she described was indirect and bypassed Dublin altogether. How could someone who’d never been to Ireland, never studied the country, know all these things?

Barker did his best to keep possibilities open, to leap through loopholes and leave the reader guessing. “I, for one, am not prepared to say reincarnation ain’t so,” he wrote.

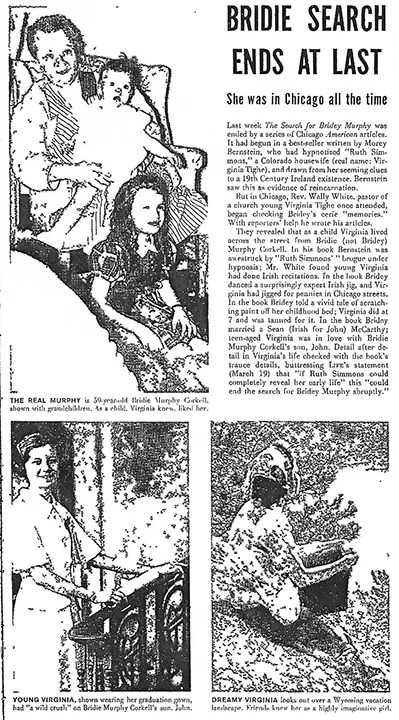

But others were. The Chicago American, a Hearst newspaper that had lost out in the bidding war for serial rights to Bernstein’s book, countered Barker’s apologia with a splashy multi-part exposé of its own. The broadsheet focused its search not in Ireland, but Chicago, where Ginni Tighe had spent much of her troubled childhood, and loudly proclaimed that it had solved the mystery.

The daughter of George and Pauline Reese, Virginia had been born in Wisconsin and lived briefly in a white frame house in Madison. But when she was three years old, her parents separated; she was sent to live with her father’s sister in Chicago. (For many years, she later said, she didn’t even know her mother was still alive.) The American claimed that she’d picked up stories about Ireland from a distant relative, acquired a brogue from youthful “dramatics lessons,” and drawn on names and incidents from her own past to flesh out Bridey’s story. The paper interviewed relatives who claimed that Virginia had been spanked as a child for scratching paint off her metal bed. Under hypnosis, Bridey had said that her husband had an uncle named Plazz, which Bernstein theorized was a convolution of the Christian name Blaize; but the newspaper located a Chicago man named Plezz who claimed to have known Virginia as a child.

There was also the matter of Bridey’s husband, Brian. Against her aunt’s wishes, in 1943 Virginia had married an Army Air Force man named Brian, who died on a bombing mission in the South Pacific months later. Hugh was her second husband, and his middle name happened to be Brian, too.

And the most startling revelation: At one point in her many moves around Chicago as a child, Virginia had lived across the street from a woman named Bridie Murphy Corkell. Mrs. Corkell wasn’t hard to find: Her son worked as an editor for the American.

Many of the conclusions reached by the American reporters were speculative or overreaching. Some of the “facts” were shaky, at best. (The paper initially asserted that Virginia, like Bridey, had a stillborn brother, then later dropped the claim.) An agenda was apparent; key sources appeared to be a sister and aunt whom Virginia hadn’t seen for years – and who clearly resented her newfound celebrity. (In a letter to Bernstein, Ginni confided that her aunt scolded her: “Remember, Virginia, there has been only one person return from the dead and that was Jesus Christ, and you put yourself on his level.”) One of the “journalists” involved was Reverend Wally White, the current pastor of the fire-and-brimstone church that Virginia had attended as a child, who made no secret of his desire to crush this reincarnation nonsense. But even allowing for the bias of her attackers, so many parallels between Bridey’s story and Ginni’s childhood were hard to explain.

“Remember, Virginia, there has been only one person return from the dead and that was Jesus Christ, and you put yourself on his level.”

Ginni was shocked by the nasty tone of the series and mortified that her brief, tragic first marriage had been divulged. She responded in subsequent interviews with Barker and another Post reporter. She said that Reverend White, whom she’d never met before, showed up at her house and offered to pray for her; he never identified himself as a reporter. The “distant relative” mentioned in the newspaper had spent most of her life in Chicago and New York and had never regaled young Ginni with Irish lore; they’d scarcely met before Ginni was eighteen. Her elocution lessons didn’t include brogues or Irish jigs. She remembered Mrs. Corkell, but didn’t recall ever hearing her first and middle names. She had no memory of a family friend named Plazz or Plezz and denied scratching paint off her bed.

“Bridey Murphy today is perhaps the most famous female name in the world,” Bernstein declared triumphantly in the spring of 1956. But after the American series ran its course, both Ginni and Hugh Tighe told reporters they wished they’d never heard of Bridey Murphy. Some days Ginni felt that “the fuss helped me mature,” but other days she wondered if she’d gotten into something that was never going to go away, a running joke at her expense, just because she’d innocently agreed to be hypnotized.

When Barker asked her if she was sorry it happened, she offered a diplomatic response.

“When I consider all the unwelcome attention it’s brought us, and how the idea of hypnosis and reincarnation offended our relatives – yes, I’m sorry,” she said. “But I can’t deny that it has been fascinating to have been the center of something which has made a great many people re-examine their faiths and beliefs.”

BUT I REGRESS

When I was in my early teens, my parents took my brother and me to a performance by the celebrated Australian hypnotist Peter Reveen. It was an entertaining, fast-moving show. Hypnotized members of the audience cavorted across the stage in all sorts of imaginary scenarios, like sleepwalkers in a madhouse. They had been told that they were ballerinas, concert pianists, champion swimmers, astronauts, gourmands tackling revolting cuisine, suave lovers – and so they were.

The grand finale came after Reveen brought his subjects out of their trances and sent them back to their seats. As he was thanking his audience, he triggered the post-hypnotic suggestions he’d lodged with his most cooperative participants. All hell broke loose as they began to act out their individual delusions as instructed. I remember one plaintive young man, earnestly explaining that the theater was on fire and we needed to evacuate immediately – and puzzling over why the crowd simply chuckled in response.

Reveen had a way of pre-screening his volunteers to make sure they were hypnotizable. At the start of the show, he asked his audience to clasp their hands together, then imagine that they were held together by an incredibly strong glue. Those who couldn’t separate their hands were invited on stage, where he tapped the hands free and kept the best subjects close by for the show to come.

Curious, I put my hands together as instructed – and found I couldn’t pull them apart. But there was no way I was going up to the stage, to cluck like a chicken or whatever. I turned to my brother, who gleefully pried my hands apart.

After a woman named Bridie Murphy Corkell surfaced in Ginni Tighe’s old neighborhood in Chicago, Life magazine declared that the search was over.

Pueblo County Historical Society

I was afraid of being humiliated, but there was no need. Reveen was proud of the fact that his show was clean and cruelty-free (with the exception, perhaps, of the would-be fire warden’s distress). He encouraged audience members to act out heroic fantasies, to slip the surly bonds of their conscious existence. “They trusted me,” he told one interviewer. “They knew I wasn’t going to make fools of them. … I helped them bring forth talents they hadn’t known before.”

Part of my fear, surely, had to do with the popular perception that people susceptible to hypnotism are fools – that they’re weak-willed, feeble-minded, gullible and so on. But the stigma is largely unfounded. Studies have drawn a distinction between hypnotizability and suggestibility; some have indicated that “good” hypnotic subjects also tend to be more open-minded and fantasy-prone, and that they probably engaged in more imaginative play as a child.

In The Search for Bridey Murphy, Bernstein contended that “normal, happy individuals” make the best hypnosis subjects; those with “real will power” tended to be the most cooperative, too. Yet there’s reason to believe that even Bernstein badly underestimated his best subject. He made the fundamental error of a pseudoscientist: attributing a bewildering result to paranormal causes rather than to flaws in the design of the experiment. The answer to the mystery wasn’t to be found in the astral world, but in the processes of hypnotism itself – and in the remarkable hidden talents of Ginni Tighe.

Bernstein couldn’t see it. Playing the patriarchal role he’d assumed – the male Svengali unlocking the secrets of a nondescript housewife – kept him from seeing it, seeing her. Reincarnation had to be the explanation, because how else could someone like Ginni come up with such a story?

“Bark, she just can’t be making these things up,” he told Barker at one point. “How could a hypnotized gal – just an everyday young married gal, with no special education or theatrical turn of mind – dream up this stuff?”

How, indeed? At its most basic, hypnotism is about the power of suggestion, the expectations implicit in the hypnotist’s questions or commands. In the first Bridey Murphy tape, Bernstein told Ginni that if she went back far enough, she would find “other scenes from faraway lands and distant places.” He was inviting her to tell him a story about a past life, and she did.

“The way the entire inquiry is framed in cases such as Bridey Murphy produce pre-ordained results,” says Gabriel Andrade, a professor at Ajman University who’s written about the ethical dilemmas posed by past-life regression therapy. “In most cases, neither the client nor the therapist is aware of what is really going on in these sessions. Both believe that reincarnation is truly happening, and that lends itself to constant confirmation bias.”

Evidence that Ginni is fantasizing or conflating scraps of information from various places rather than recounting actual memories can be found on that first tape even before the past-life regression begins. She mentions the “cotton dolly” she had at age one, but scientists say that retrieval of such an early experience is physiologically impossible.

“We can pretty much discount anything you remember before two and a half, maybe three and a half,” says Charles A. Weaver III, chair of Baylor University’s department of psychology and neuroscience. “People who say they have memories from the age of one or two – we just don’t have the brain structure to form those memories. They have likely been suggested or cobbled together because we’ve seen pictures from our childhood or heard stories from parents.”

Weaver has written extensively about hypnosis and false memories; he points out that the unreliability of what’s dredged up under hypnosis is the reason that “hypnotically refreshed” eyewitness testimony is no longer permissible in court. And past-life regression?

“I don’t think there’s a shred of scientific evidence behind it,” Weaver says. “Hypnosis has some clear benefits in areas like pain control. It increases the amount of things people remember. But it creates false memories as well, and there’s no way to distinguish between the two.”

“In most cases, neither the client nor the therapist is aware of what is really going on in these sessions.”

Researchers have attributed the “stuff” Ginni came up with to a phenomenon known as cryptomnesia. It’s possible to remember something you haven’t thought about for years, but not recognize the information as a memory – rather, it’s viewed as something new. For example, a writer produces a story that appears to be utterly original – but it turns out to be inadvertently plagiarized, borrowed from something the author read (or wrote) years ago. Similarly, elements of Ginni’s story appear to derive from childhood details she’d long forgotten but unconsciously retained, such as the names “Bridey Murphy” and “Plazz.”

The process certainly wasn’t as simplistic as the Chicago American made it out to be. Bridey’s white frame house could have come from anywhere; it didn’t have to be the particular house Ginni lived in as a child. The story she told was a complex yet spontaneous construction. Some of it derived from childhood episodes and associations, but other parts were apparently invented, springing from a well-stocked imagination.

Never mind all that talk about not having an encyclopedia or even a library card. Ginni Tighe was a voracious reader, and readers store up all kinds of information they don’t know they have. She admitted as much in a letter to Bernstein. Although she’d never formally studied Ireland, she wrote, “I’ve read a lot in my life, and somewhere in the back of my mind these facts may be secreted away.”

Under hypnosis, an avid reader might have access to unusual bits of geography and history, trivia about nineteenth-century Irish customs and crops, even some acquaintance with the exploits of Cuchulain – without knowing how to pronounce his name. Some obscure but historically accurate details in Bridey’s story remain unexplained to this day, but that’s hardly proof of mystical origin. “The fact that we aren’t able to identify the source of her information doesn’t mean the source isn’t there,” Weaver notes.

Bernstein couldn’t accept that he had brought forth remarkable storytelling abilities in an “everyday young married gal.” He believed he had stumbled onto something much bigger, even if he couldn’t explain how it all worked. And the lack of an elaborate doctrine of reincarnation turned out to be part of the book’s appeal. Despite the debunkings, The Search for Bridey Murphy continued to find an audience among those interested in the paranormal. It sold so well, in fact, that Doubleday eventually issued a revised edition, incorporating Barker’s research and rebuttals to the book’s critics.

“Bridey is beginning to move now as a classic,” Bernstein reported to Ginni in the early 1970s. “It should; tiz far and away the best book in the entire parapsychological field.”

As the years passed, Bernstein became increasingly contentious about protecting his turf. He threatened defamation suits against people who referred to his experiments as a hoax; he even took on Stephen King for a disparaging reference to Bridey in his nonfiction book Danse Macabre. (King’s lawyers brushed him off.) Bernstein also complained that other reincarnation-themed projects, such as the Broadway musical and film On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, were ripoffs of his work. In 1985 he hectored Cecil Adams, the pseudonymous author of the widely syndicated “Straight Dope” column, for daring to suggest that the Bridey Murphy experiments had been discredited.

“Every single item that attacked Bridey was torn to shreds,” Bernstein insisted, “while even the most recondite facts that Bridey gave forth during hypnosis were 100 percent correct.”

At least, that’s the way he remembered it.

By that point, Bernstein had become a recluse. He’d moved out of his large house and into a modest apartment. His health issues kept him housebound, and eventually bed-bound. Some locals described him as “the Howard Hughes of Pueblo.” But he was also known as one of his home town’s greatest philanthropists, having donated valuable parcels of land to the University of Southern Colorado and for a local arts center and convention center. He died of an irregular heartbeat in 1999, at the age of 79.

Ginni Tighe remained ambivalent about Bridey Murphy. She moved to Littleton, prized what was left of her family’s privacy, and only reluctantly granted occasional where-are-they-now interviews to the Denver newspapers. Yet she also appeared twice on To Tell the Truth and accepted an invitation to visit the set of the 1977 horror movie Audrey Rose. She toyed with the idea of writing her own memoir of her adventures in hypnosis; it would be “a report of what happened to an individual who suddenly is the subject of something so highly publicized and controversial.”

She never wrote it. She and Hugh divorced in the late 1960s; three years later, she married Richard Morrow, a steel company executive. When she died in 1995, at the age of 72, she was the matriarch of a far-flung clan that included three daughters, a stepdaughter and stepson, and ten grandchildren.

She and Bernstein saw little of each other in the last three decades of their lives. But they remained friends. At one point Bernstein asked her to prepare a press statement, correcting false reports that they were now enemies and saying that she would welcome more sessions with her Svengali. She wrote back, making it clear that she had no interest in being hypnotized again. At the same time, she admitted that her beliefs about reincarnation remained fluid – some days yes, some days no.

“The whole experiment was honest and uncontrived from the inception to the present day,” she wrote. “I must admit today my leanings are toward Bridey – why not?”