Andrew Nilsen

Audio By Carbonatix

Rhidale Dotson knows what it’s like to be labeled. “Most people see me as a criminal,” he says. “Most people see me as this green jumpsuit and this DOC number on my name tag.”

He sits in the visiting room of Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility in Ordway, a place of somber concrete walls and razor-wire-topped prison fences far out in the desolate expanse of southeastern Colorado. The name tag on the chest of his green jumpsuit is stamped “86988”; that’s the number that’s been following him since he was convicted of conspiracy to commit aggravated robbery at age seventeen, before he was charged and later found guilty of murder sixteen years ago and sentenced to life without parole.

But with every gesture, every statement, Dotson fights back against that label. His dark eyes warm and welcoming, he engages everyone in the visiting room like a friend and colleague – inmates and prison guards, black prisoners and white. Gesturing excitedly with his well-toned arms and sketching out elaborate diagrams on pieces of scrap paper, he pontificates on obscure topics like a college professor: the best models for successful business management, the outdated-ness of most concepts of criminality, the limitations of prison administration hierarchies. The forty-year-old acts like a man brimming with hope and ambition, like someone who gets things done.

That attitude is justified: Over much of the past decade, Dotson and several other inmates at AVCF developed a series of revolutionary programs. While prison gang violence was escalating statewide and was eventually at least partly responsible for the shocking 2013 murder of Colorado prisons chief Tom Clements, Dotson and his fellow prisoners were building programs that challenged the way most correctional facilities handle gang violence. Their approach was so successful that Colorado Department of Corrections administrators transferred several of the state’s top gang leaders to AVCF and let Dotson and his colleagues facilitate an entire prison pod where major gangbangers – Crips, Bloods, Sureños, Aryan Circle, 211 Crew – lived together in an environment that felt more like a business accelerator than a prison block. And it worked.

“The inmates who worked on this program worked very hard and should be commended,” says Mark Flowers, who served as the state prison director for four months after Clements was killed. “They are a very special group of inmates who have a special gift from God.”

The DOC’s current administration won’t comment on what Dotson and his colleagues built at AVCF. “The Department of Corrections is committed to the safety and security of all offenders,” notes DOC spokesman Mark Fairbairn in an email statement. “It is difficult for offenders to break the cycle of gang violence, and we believe that bringing attention to their efforts puts them and others in danger.” But that doesn’t mean that those in charge aren’t paying attention: In March, the DOC launched what it called “a more effective, leading-edge approach to gang intervention,” one that it hopes to implement in prisons statewide. The program was directly inspired by the work of Dotson and his fellow inmates.

Dotson and the others weren’t officially recognized for their work on the project. In fact, the inmates are no longer involved with the program they helped launch. Once again, it appears they’ve been labeled: a political and bureaucratic liability, a resource that’s meant to be used.

It’s one more label that Dotson won’t accept. He’s already hard at work on new prison gang programs, new efforts to transform the cycle of violence and incarceration that led him to a life behind bars. “My goal is to get bigger than prison,” he says. “I have so many plans, it’s crazy.”

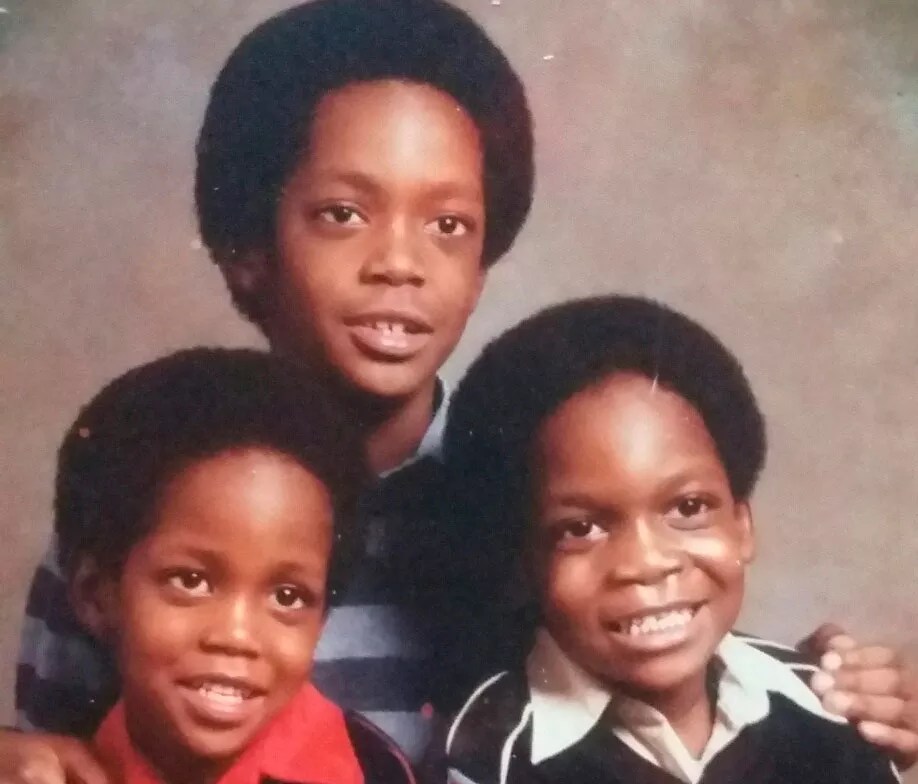

Rhidale Dotson, right, with his brothers. Dotson excelled at school – until he got into robbery.

Courtesy of Priscilla Sutton-Shakir

The DOC currently refuses to allow Dotson in-person media interviews, where reporters would be able to record the conversation or take notes. Instead, the details of his story must be gleaned from twenty-minute pre-paid phone calls – calls that accumulate into hours upon hours of conversation, since Dotson is not fond of brevity.

“My friends say that if someone asks me what time it is, I will end up telling them how to build a clock,” he says with a laugh over the phone, the sounds of slamming cell doors and security buzzers echoing behind him. His tale is adorned with verbal footnotes and sidebars, detailed explanations of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning Domains, the Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership Theory, neurolinguistic programming and other esoteric concepts he’s studied. He excitedly describes various nonprofits and entrepreneurial ventures he’s developing, part of his mission to write 24 business plans a year.

“I am always trying to figure out my next move,” Dotson says. “How can I be productive in here, regardless of the circumstances?” That’s the best way to survive “a system that is meant to keep people in their cycles,” he explains: watching TV, playing cards, working out ad nauseam, until before you know it, ten or fifteen years have passed and you’ve accomplished absolutely nothing.

Dotson has never been one to succumb to that sort of idleness. “I am good at surviving,” he says. “I am good at making it.” That survival instinct kicked in early, when he was six or seven and fell out of a third-story window in the Aurora apartment complex where he was living, landing in a bed of rocks. In what he and his family saw as a bona fide miracle, he quickly recovered from the fall, eventually becoming a championship diver at Montbello High School. Meanwhile, school itself was never a problem. “Rhidale was exceptional,” says his mother, Priscilla Sutton-Shakir. “He didn’t have to study to ace a test. Thoughts would come to him way beyond his youth.”

When Dotson was in fourth grade, his mother married Denver anti-gang activist Leon Kelly and helped him launch the Open Door Youth Gang Alternatives program. “Rhidale was always an innovator,” Kelly says. “He was a smart kid. He had so much potential as a youngster growing up.” But before the two divorced in 1994, Dotson was already finding himself lured toward the violence and lawlessness his mother and stepfather were working to combat. “I like to think between me and his mother, we tried to do the best we can,” Kelly adds. “He was the one who certainly had the leadership ability. But some of the choices he made were regrettable choices.”

Unlike many of his friends in Montbello and on the east side, Dotson never officially joined either the Bloods or the Crips; as a natural-born street fighter, he didn’t see the point. “I could whup most of you anyway,” he remembers thinking. “Why would I join you?” But he did fall into petty crime and then larceny. “I remember the first burglary that I did: The adrenaline is pumping, knowing you’re doing something wrong,” he says. “It feels awful, but when you get away with it, the next time it’s not as hard. The next time after that, it’s even easier.”

School soon took a back seat to robbery and his other habits: doing drugs, getting in fights, chasing girls, living on the street. At seventeen, a botched carjacking led to a three-year sentence at the Youthful Offender System, a maximum-security prison for young inmates. While incarcerated, Dotson earned his GED, started taking college courses and overhauled the Rams Club, the prison’s high-achiever program, largely because he was bored and looking for something to do. But after he got off parole in 1998, he returned to robbery to fund his dream of starting a record label. That’s when circumstances spiraled out of control.

In May 1999, Dotson and a partner held up Jason Alyn Trefny, a 23-year-old Metro State college student, at his parents’ home near Denver International Airport after reading in a classified ad that he was selling stereo equipment. A tussle broke out, and someone fired a pistol. At the time, he didn’t realize Trefny was hit, Dotson says; Trefny said he was having trouble breathing from an asthma attack. But after the robbers left, Trefny was found dead in his basement, shot in the lung. Two years later, in September 2001, an Adams County jury found Dotson guilty of felony murder and robbery for the slaying. (Similar charges had been filed against Dotson’s younger brother, Raymond, for the crime, but they were eventually dismissed.) By that point, Dotson had already been sentenced to 45 years for a separate robbery in Arapahoe County. Now he was given life without parole.

“That was the last time I took a real deep breath,” says Dotson. “After that, it felt like something was constantly trying to choke you out. It’s like having a boa constrictor around your neck.”

But Dotson was a fighter. He fought his convictions in court, attempting every sort of appeal. And he fought his way through prison, cementing his reputation at AVCF as someone who wasn’t to be messed with, someone willing to do whatever it took to win a brawl.

By 2010, though, the fight was nearly out of him. His legal appeals hadn’t gotten him anywhere, and he’d realized that if he wanted to make amends, he had to admit to himself and others that he was guilty. The woman he’d been planning to marry before his conviction had long since cut off all contact, and other romantic relationships he’d fostered while in prison had fizzled out, too. His biological father, with whom he’d been close, had recently passed away. And the reality of his situation was dawning on him. “If you really believe you have a life sentence, you realize you really just have a long death sentence,” he says. “If you ever give up hope, you might as well just lie down and die.”

Dotson was close to lying down. That’s when a friend, Cedric Watkins, handed him a piece of paper that changed everything.

Cedric Watkins realized the prison system didn’t have any programs to help gang members like himself – so he decided to create one.

courtesy of Rhidale Dotson

Like Dotson, Watkins was nearing rock bottom at the time. Born and raised in Park Hill, he’d found escape and protection from an abusive home life in the local Crenshaw Mafia Bloods, then worked his way up until his nickname, “Baby Brazy,” rang out as one of the top generals in the gang. He’d caught eighty years behind bars for robbery, part of which he’d already spent in administrative segregation – or long-term solitary confinement – at the maximum-security Colorado State Penitentiary before getting transferred to AVCF in 2009. But now he had nothing left to prove to his fellow gang members, nothing left to accomplish. And recent news that his wife had cheated on him rocked him to the core. “Everything in my life suddenly had no meaning,” Watkins says over the phone from Ordway. “I looked around and decided I was probably better off sitting by myself in ad-seg in CSP. If they let me out, I’d just start my next wave of chaos.”

But instead of getting himself shipped back to the state penitentiary, Watkins noticed something one day at AVCF: a line of prisoners, each carrying a file folder, heading to a class for sex offenders. In his head, something clicked. “I looked at that and I’m like, ‘This is some bull. How is it they have all this stuff for those guys, but they don’t have anything for someone like me?'” he says. “I don’t know the first thing about how to get my life in order. I am addicted to gangs. But what does DOC have in place for gang members?”

Watkins wasn’t the only one starting to ask questions about what the DOC was doing about prison gangs. As in many other states, Colorado prisons are now home to a dizzying patchwork of gangs, often but not always delineated by ethnicity. African-American prisoners have the Bloods and Crips, plus other, less extensive gangs like the Gangster Disciples and Almighty Vice Lord Nation. Among white prisoners, there is the Aryan Circle, the 211 Crew and other white-supremacist gangs. And Mexican-Americans and other Latino-Americans often join Norteños, Sureños, Los Primeros Padres and Los Aztecas. The volatile mix has led to tense prison environments where looking at the wrong guy, saying the wrong thing or even just singing the wrong song can trigger a riot. While the DOC’s parole and inmate population dropped nearly 10 percent between 2011 and 2015, prison fights, inmate assaults and other markers of violence are on the rise.

“I am addicted to gangs. But what does DOC have in place for gang members?”

According to the DOC, there are now more than 8,000 gang-affiliated inmates and parolees in Colorado divided between at least 135 gangs. That means that roughly one out of every four people in the state prison system is labeled as being in a gang. And there are now more gang members in prison than there are total DOC employees.

Gangs have become so widespread that research suggests they have evolved into a major and vital part of the prison ecosystem. David Skarbek, a senior lecturer in political economy at King’s College London, has spent years studying the extensive gang culture within the California prison system. He’s found that far from being agents of chaos and upheaval, gangs took hold among ballooning prison populations as a way to establish social stability. “In lots of important ways, gangs promote order in a potentially disorderly environment,” he says.

“They provide guidance because stable prisons are profitable prisons. Gangs only make money when prisons are being run well.”

That’s why the typical prison approach of breaking up gang members or locking up gang leaders in solitary confinement doesn’t help. “Suppression strategies that isolate gang leaders or gang members have failed to stop gang activity because it ignores the fact that prisoners have a demand for gangs,” says Skarbek. “Prisoners want to be safer, so they turn to gangs. Prisoners want drugs and order in the underground economy, so they turn to gangs. There are demand-and-profit opportunities for people to provide these services, so when you remove one ‘entrepreneur’ and the demand remains, new people will step into those profitable roles.”

Watkins knew that punitive gang-management measures were never going to work for him or for gang culture at large. Gang members’ ideological convictions were too powerful, the organizations too vital to their identity and daily lives, to allow them to be lured away from gang-banging without getting something more attractive in return. “It doesn’t make sense that gangs are your number-one problem and you don’t have anything for these guys to better themselves,” says Watkins.

So Watkins wrote up an alternative on a piece of notebook paper, one he called the “Gang Awareness Program,” or GAP. The idea was to teach inmates that there were things in their lives – their family, their community, their religion and their career goals – that were more important than gang affiliation, that would help them shift from a culture of blame and retaliation to one of responsibility and hope. The most crucial, and most groundbreaking, part of the proposal was that participants would be selected from the existing prison gang leadership, and they wouldn’t have to renounce their gang ties in order to join the program. Watkins wanted to have participants focus on productivity and creative endeavors rather than destructive habits and violence.

Watkins submitted his idea to AVCF administrators – and he also shared it with Dotson. The two had been close since grade school, calling each other “famo.” And while Watkins knew Dotson could be raw and violent, he also recognized his friend as blisteringly intelligent. If there was anyone who could help make the plan a reality, it was Dotson.

Sure enough, by the time prison administrators surprised Watkins by agreeing to let him pursue his idea, Dotson was already hard at work. “GAP was a real-life game-changer,” says Dotson. “People here have good skill sets; they just happen to be skill sets that are used to break the law. Now we had a chance to showcase that we had legitimate skill sets, that we had actual value. And we were doing it without selling out.”

Rhidale Dotson, right, grew up as a fighter. In prison, he’s fighting to transform gang culture.”

Courtesy of Priscilla Sutton-Shakir

In his free time, Dotson pored over relevant books and materials from the prison library, studying up on psychology, sociology, addiction, self-help, human resource management, learning styles and leadership development. Using a storage closet as a makeshift office and an old computer to which he’d been given access, he sketched out plans for curricula, cost structures, team objectives, motivation strategies, program assessments and scalable systems, designing them to be relatable to the culture of the prison yard. The goal was to help participants identify objectives that really mattered to them, then connect them with skills and resources to reach their goals. “It’s not necessarily about staying out of trouble; it’s about being productive,” says Dotson. “If you’re spending the majority of your time being productive, you won’t have time to cause trouble.”

At pitch meetings to prison staff and DOC administrators – held in public places, to keep the process as transparent as possible – Watkins would recount his life story to illustrate why he needed help, while Dotson would explain how GAP would be able to provide help. “We called each other the ‘one-two,'” says Watkins. “I hit them in the gut, he hits them in the head.” And while Watkins was at first nervous about speaking in front of prison officials, a supportive prison guard set him straight: As a gang leader, he’d commanded crowds of drug dealers and killers. Why should he be afraid of a room full of bureaucrats?

Dotson brought in another collaborator: Shane Davis, a major player among the Crips. Despite their rival affiliations, Watkins and Davis grew close, and together the three worked to earn support of other prison gang leaders. “This is not a gang-renunciation program,” Watkins remembers telling them. “If you don’t want your homeboys to be in on this, you have to question your place as a leader.”

Once everyone signed off on the effort, the trio recruited a core group of shot-callers from the various gangs, then ran them through an intensive twelve-week training regimen so they could become program facilitators. Then, after more than a year of prep work, they earned final approval from DOC brass to move forward. In early 2013, Dotson, Watkins and Davis held a rambunctious launch event in the prison gym, where hundreds of gang members learned about the new program, one designed for inmates by inmates. “It became more than an idea,” says Dotson. “It became a movement.”

But that movement soon came to an abrupt halt. On March 19, 2013, DOC executive director Tom Clements was shot and killed at his Monument home by Evan Ebel, a parolee who had recently been released from Sterling Correctional Facility and had ties to the 211 Crew. “We were crushed,” says Watkins of losing Clements, who had been laboring to wean the DOC off of its excessive use of administrative segregation. “Here was someone who was working for us.” More pressingly, the murder jeopardized the prison reforms begun under Clements’s watch. While his replacement, Mark Flowers, spent time at AVCF and came away impressed with what Dotson and his colleagues were building, he resigned just four months into the job, before he could become a true champion of their program. Between the upheaval within the DOC and a major staff shakeup at AVCF, GAP was put on hold indefinitely.

But not for good. While investigators never concluded that Ebel, who killed himself in a shootout with Texas authorities two days after slaying Clements, was acting on the orders of the 211 Crew, his ties to the organization put pressure on the DOC and its new director, Rick Raemisch, to do something about gangs in their facilities. Eventually, prison administrators realized they already had something they could try.

In April 2014, Dotson and his collaborators were called to a mass meeting of prison wardens at AVCF. They wanted to re-launch GAP, but on a wider scale. How would the inmates feel about facilitating an entire prison pod, where all 45 to 60 inmates would be part of the program?

All the Mexicans, blacks and whites were kicking it. There were no fights, and we were learning.”

Despite misgivings over having so many gang leaders living in such close quarters, GAP’s founders were willing to give it a shot. In just two weeks, they recruited enough participants to fill what they’d termed “The Embassy Pod,” then designed the unit to suit their needs. Part of the pod became a work office, with computers and file cabinets filled with training materials.

Communal tables previously used for poker games and chess matches were soon surrounded by guys studying business books and completing homework assignments. And every inmate had a white board affixed to the wall by his cell door listing what project he was working on, whether it was pursuing a legal appeal, developing an entrepreneurial venture, writing a book or reconnecting with family members with whom he’d lost touch.

Days began with energetic music blasting through the pod, followed by inmates gathering for classes usually taught by Dotson. He drilled them on emotional intelligence, problem solving, goal setting and how to deal with stress. He devised exercises to illustrate difficult concepts: He’d have as many guys as possible pile onto a couch, then challenge others to try to push and pull it here and there, to demonstrate the different forces at play when you try to accomplish positive change. To keep everything as transparent as possible, the Embassy Pod was always open to visitors – DOC brass and gang leaders alike.

Soon GAP’s impact was being felt throughout the facility. In the chow hall, Bloods and Crips and 211 Crew members started breaking bread together. GAP’s co-creators even persuaded prison administrators to transfer several of the state’s top prison gang leaders, including 211 Crew founder Benjamin Davis, to AVCF so they could be part of the effort.

“All the Mexicans, blacks and whites were kicking it. There were no fights, and we were learning,” says Dotson. “Nobody has ever been able to do that.” According to Dotson, Watkins and several outside experts who communicated with AVCF staff about the program, the number of gang-related incidents at the facility dropped to nearly zero.

“The program was amazing. It inspired me to take control of my life,” says Alan Sudduth, an AVCF inmate with ties to the Rollin’ 30 Crips. “There’s nothing like that being taught by those who have been or currently are in the struggle of redefining yourself and not forgetting where you came from.”

But as the months passed, the Embassy Pod ran into trouble. Davis was transferred to another facility, while Watkins was removed from the program for inappropriate relations with a female staff member. After he was kicked out, DOC Deputy Executive Director Kellie Wasko, who’d become a champion of the program, visited Watkins in his cell and chewed him out. “She stood in my room and she’s like, ‘What were you thinking?'” he remembers. “By getting on my ass, she showed me she gave a damn.”

That left Dotson to run the show more or less on his own, a job that became more difficult once the prison began housing non-GAP inmates in the pod to fill empty beds. It didn’t help that some program participants couldn’t keep up with the pace of the lessons and started checking out. Then in early 2015, several Embassy Pod inmates concocted a hefty batch of prison hooch and started passing the moonshine around. One thing led to another, and a scuffle broke out. While Dotson says no one even got hit, prison staff took the incident to signify that GAP had run its course. While Dotson and his colleagues were placed in lockdown in their cells, guards dismantled and carted away everything: the computers, the file cabinets, the white boards listing all of their goals.

“That was the worst feeling,” says Dotson. “It was like being stripped naked.”

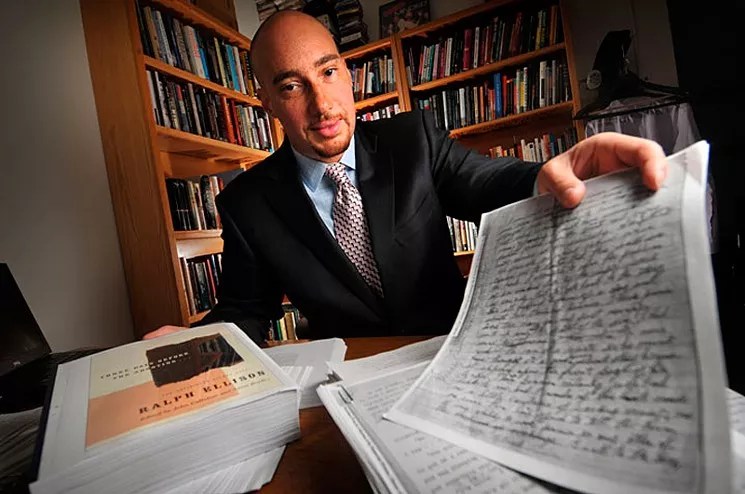

Adam Bradley offered to help Dotson.

Courtesy of Glenn J. Asakawa-University of Colorado

But the Embassy Pod had left an impression on AVCF staff. At the same meeting where they learned the program was being shut down, Deputy Executive Director Wasko and the prison’s warden told Dotson and Watkins that they could try again. While Watkins kept working with gang leaders, building upon the groundwork they’d laid with GAP, Dotson began envisioning a new program. He simplified the curriculum and incorporated more evidence-based approaches. And he got rid of the name “Gang Awareness Program,” since this time he wouldn’t just be targeting gang members, but high-risk inmates in general. Instead, he called it the Three Keys Project, illustrating the three phases of rehabilitation that participants would undergo: They would reassess their goals and interests, move beyond criminal living, then add value to their community through active citizenship.

This time Dotson sought outside help, including Adam Bradley, an English professor at the University of Colorado Boulder and founder of the school’s Laboratory for Race & Popular Culture (RAP Lab). Bradley had learned of Dotson’s work through the director of a prisoner advocacy group and reached out to the inmate. Soon Bradley was connecting Dotson with experts in education theory, sending him business-management training manuals, and calling him every week to act as a sounding board. It didn’t take long for the two to become close friends. “Rhidale is functioning at such a high level and integrating all of these disparate strands of thought and practice into a thread of his own design,” says Bradley. “It’s the mark of an autodidact; I’m fascinated with the way his mind works. I wish I had more grad students like him.”

By the summer of 2016, Dotson was ready to launch Three Keys. But that’s when DOC brass once again called him, Watkins and another collaborator to a meeting and once again threw them a curveball: The DOC was planning to launch a system-wide gang-intervention program, one that was built on the ideas pioneered in GAP. At first it seemed to Dotson and Watkins that the sit-down was a formality, an opportunity for administrators to acknowledge the inmates’ work before moving on without them. But once Dotson and Watkins began firing off pointed questions – How were they going to incentivize participation? How were they going to get sign-off from gang leaders? How were they going to assess program results? – it became clear that the bureaucrats could use the inmates’ help.

“Our relevancy will eventually wane. Someone else has to take the torch and do better, be better.”

Setting Three Keys aside, Dotson again joined forces with Watkins, and the two set to work. The result was a rehabilitation strategy that would offer gang members continuing guidance and support as they moved from one DOC facility to the next, and eventually into the outside world. They called the program “Leaders to Inspire Visions of Excellence,” or iLIVE. “We are in a culture of people being ready to die for what they believe in,” explains Dotson. “If you get them into a culture where they say, ‘I live,’ that changes them.”

It helped that the new program was being facilitated on the outside by Sean Ahshee Taylor, an ex-gang member whose first-degree-murder sentence had been commuted by Governor Bill Ritter in 2011 and who now worked as deputy director of the Aurora-based Second Chance Center, a nonprofit that helps inmates re-enter society. Taylor had been incarcerated at AVCF and had witnessed Dotson and Watkins in action. “When the Department of Corrections first approached me and said, ‘We would like your help dealing with the [gang] problem in the Department of Corrections and asked me for my suggestions,’ I said, ‘You already have a program in the Arkansas Valley Correctional Facility called GAP,'” Taylor recalls.

Dotson and Watkins’s help with iLIVE proved that his recommendation was well founded. “Those two individuals are so amazing,” Taylor says. “They took the time, knowing full well that whatever they wrote was going to be property of the Department of Corrections, that it was not going to belong to them anymore. They just wanted to help people.”

Dotson and Watkins were under the impression that they would be an integral part of iLIVE, but that assumption proved incorrect. At first the two were told it was possible they could be transported to various DOC facilities to help with staff trainings, but administrators later backtracked on the offer. Then plans to include Dotson and Watkins on various program meetings via the prison’s teleconference system kept getting pushed back. Finally, they were told to be ready to be patched into a staff training session this past spring at Colorado State Penitentiary, where the new program was set to be launched. That day, Dotson and Watkins sat waiting in AVCF’s teleconference room, but the call never came. They were never again given an opportunity to participate.

Dotson wants to remain hopeful about the new twelve-week gang program, which has been completed at CSP and will reportedly soon expand to Limon Correctional Facility. “If there’s anyone who can pull it off, it’s Sean,” he says. But he was frustrated when the DOC’s March 27 press release announcing the program, which noted GAP as a core inspiration, labeled the effort the “Colorado Department of Corrections Gang Disengagement Program.” The name suggested the sort of severe, all-or-nothing anti-gang approach they had worked so hard to challenge. While Taylor is adamant that the program continues to be called iLIVE, Dotson is also concerned by reports he’s heard that the program so far has been populated by low-level gang members, not the sort of major shot-callers the DOC considers the biggest threat – and who Dotson figures will be necessary for the project to truly thrive.

“The dudes they selected probably aren’t the type of dudes we designed the program for,” he says. “It is probably very successful for the dudes who are currently in it, but it’s going to be hard for them to institute systematic change.”

Dotson isn’t giving up. He and Watkins recently launched iLIVE Remix, a leadership program for young gang members at AVCF. “They are the next generation of leaders. They are the ones who will shape the culture moving forward,” says Dotson. “Our relevancy will eventually wane. Someone else has to take the torch and do better, be better.”

The program is already having an impact. Dotson recently saw one of the participants and asked him, “What’s up?” In the past, this was the sort of guy who’d just say, “I’m cool,” and move on, keeping his head low and doing his time. Instead, he flashed Dotson a confident smile and said, “I’m trying to make something happen!”

“If he had been able to display some of the talent on the outside that he displayed on the inside, man, maybe he would have been able to follow in my footsteps somewhat,” Kelly says of Dotson.

The original iLIVE program could eventually come to AVCF – and when it does, Taylor promises, those who helped develop the effort will have a chance to help run it. “These guys, I don’t care if it’s GAP, iLIVE, iLIVE Remix or something with no title at all – these are two men who want to do good things and influence the world in a positive way,” says Taylor, his eyes filling with tears as he sits in the Second Chance Center. “I will always help them with that.”

Dotson has also been working on another project, one that’s more personal. When he first started working on GAP in 2010, he was doing so to help Watkins and others looking for a way out of the gang lifestyle. But soon he began internalizing the lessons he was developing, realizing that he, too, needed to change. He stopped fighting in the prison yard and instead started fighting for redemption. He wrote letters of apology and remorse to the family of Jason Trefny and others he’d hurt during his robbery days, offering his services if he could help them heal, if he could help them move on. Since offenders aren’t allowed to contact victims directly, the missives are stored in the DOC’s Apology Letter Bank, and they can only be released if the victims ask for them.

This past June, Dotson submitted a clemency request to Governor John Hickenlooper, a lengthy application he spent months compiling that included descriptions of the various prison programs he’d helped develop and letters of support from people he’d worked with, including Adam Bradley. He figures he has a pretty good shot at clemency – but he knows nothing is certain. He doesn’t like to think too much about what will happen if his application is rejected, if he has to face the fact that he’s likely going to be in prison for the rest of his life.

“There is a danger of me at some point in time burning out,” he says. “Maybe I get tired of the fight. If that happens, I don’t know. To have put in that much effort, to have worked so hard for so long, man…” He pauses. “This is a very dangerous place to put a human being in. A place with no hope? That’s hell.”

But even if Dotson stops fighting for his freedom, even if he gives up hope of ever getting out, he won’t regret the work he’s accomplished along the way. “I have helped people go home, I have helped make things better for my community, and spiritually I have benefited from doing service,” he says. “I am not doing this transactionally. I am doing this for transformational change. I am doing this because it is the right thing to do. And while there are a lot of rules in prison, there’s no rule against doing right.”