Brooklyn Museum

Audio By Carbonatix

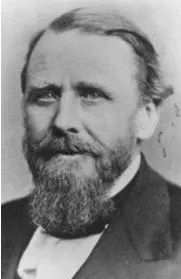

On November 17, the Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board voted to recommend to change the name of Mount Evans, the 14,265-foot peak that honors John Evans, Colorado’s second territorial governor – and the man who created the climate that made the Sand Creek Massacre possible, according to an investigation of his actions by the University of Denver, which Evans founded in 1864. At dawn on November 29 of that year, approximately 675 U.S. volunteer soldiers commanded by Colonel John M. Chivington attacked a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians camped along Sand Creek; about 200 were killed, most of them women, children and elderly men.

The board chose Mount Blue Sky from five suggestions, which also included Mount Cheyenne Arapaho, Mount Blue Sky, Mount Soule (honoring Silas Soule, the captain who refused to participate in the massacre, testified against Chivington, and was assassinated on the streets of Denver in 1865), Mount Sisty and Mount Rosalie. That’s the name that was given the peak back in 1863, as outlined in this chapter of the book Colorado’s Highest: The History of Naming the 14,000-Foot Peaks, written by Jeri Norgren, with photographs by John Fielder.

Here’s the lowdown on how one of Colorado’s tallest mountains got its name:

Mount Evans, the majestic lofty peak dominating the western skyline of the Colorado plains, may be seen from as far away as 100 miles to the east. It commands attention on clear days and is exceptionally magnificent when blanketed in snow. This name for the tallest peak in the Chicago Mountains was not the first choice, nor did it come by its name easily. Mount Evans was originally named Mount Rosalie as a monument to romance but was later rechristened in honor of a popular political hero of the time.

The story begins in 1863, when the renowned landscape painter Albert Bierstadt, at the young age of 33, traveled west in search of a subject for a great Rocky Mountain picture. On this, his second expedition to the Rocky Mountains, he was accompanied by his friend Fitz Hugh Ludlow, a celebrated writer and author of The Hasheesh Eater, a popular counter-culture book of the time, and literary editor of the New York Evening Post. Two other gentlemen, Messrs. Hall and Durfee, came along merely for the adventure. Bierstadt’s goal was to sketch mountain scenery, Ludlow’s was to chronicle the trip, and Messrs. Hall and Durfee “…for aught we know, travel simply for the pleasure of doing so.” Ludlow’s subsequent writings find them referred to as the “two other Overlanders,” and Bierstadt became “the artist.”

On June 8, 1863, the four traveling companions arrived in Denver on the first leg of a journey that would eventually take them to Salt Lake City, California, Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. According to Ludlow:

“In a few days we were so thoroughly rested that we became tired of having nothing to tire us. We proposed to ourselves at least two subordinate trips out of Denver before we should finally leave the place for Salt Lake: the first to Pike’s Peak, with the remarkable scenery and geological formations lying between it and Denver; the second to the chief Colorado gold mines and their business nucleus at Central City.”

The four friends, joined by Judge Benjamin Hall and General John Pierce, departed Denver on June 10 for Pikes Peak and the Garden of the Gods, having been offered the use of wagons and horses by Governor John Evans and Pierce. With Pierce piloting the expedition, they traveled south and were thrilled with all they saw. Although Bierstadt sketches much of the scenery on this side trip, his studies were never incorporated into a painting. Ludlow expressed his dismay when he wrote:

“It was a great disappointment to some of our kind friends that our artist did not choose the Garden of the Gods for a ‘big picture.’ It was such an interesting place in nature that they could not understand its unavailability for art….But the artist’s selective faculty is not to be looked for among practical men.”

Upon their return to Denver a few days later, Pierce introduced Bierstadt to William N. Byers, pioneer editor of the Rocky Mountain News. “He (Bierstadt) came first to Denver, in search of a subject for a great Rocky Mountain picture, and was referred to me – probably because I had at the time the reputation of being something of a mountain tramp,” Byers noted at the time. It was said Byers knew more about Denver and the surrounding area than anyone. He happily agreed to act as tour guide accompanying Bierstadt into the mountains while Ludlow, Hall, and Durfee went on to Central City.

On June 17, Byers and Bierstadt left Denver in a “wheeled conveyance” heading toward Idaho Springs, where they spent the night. The next day they set out on muleback and began their journey up Chicago Creek to the base of the brooding Chicago Mountains. Byers wrote:

“The route up Chicago Creek – the one we had chosen – is difficult and tedious. Alternately through swamps, over rocky points, winding among fallen timber and tangled underbrush, it is no place for broadcloth or fancy outfits; places so indistinct as to be followed with extreme difficulty, and occasionally it disappears altogether. Mr. Bierstadt was in raptures with the scenery, but restrained his inclination to try his pencils until within two or three miles of the upper limit of tree growth. There upon suddenly turning the point of a mountain and entering a beautiful little grassy park, a vast amphitheatre of snowy peaks, lofty cliffs and timbered mountain sides burst suddenly upon the view. Patience vanished, and in nervous haste, canvas, paint, and brushes were unpacked and a couple of hours saw, under his skillful hands, some miles of mountain, hills, forests and valley reproduced with all of its vivid coloring and the loud shadows that were sweeping over it.”

They continued climbing and, after a short time, arrived at Trout Lake, where they camped for the evening on its northern border, “beside the great waterfall of this country, and at the foot of an immense rock cliff, over which comes the stream. A more beautiful or romantic spot cannot be pictured even in imagination,” Byers noted. They awoke before sunrise on June 19, shook frost from their blankets, and broiled trout for breakfast in hopes of reaching the mountaintop before the sun rose – a misguided and ambitious goal. They climbed to another lake enclosed in an amphitheater similar to the one below, then on to a third lake up a weather-worn gorge between lofty vertical walls whose difficulties they likely underestimated. This highest lake they christened “Summit Lake,” a name that still stands today.

“This is the largest and loftiest lake in this portion of the Territory,” Byers wrote. “Its altitude cannot be less than twelve thousand five hundred feet. In form of outline it is a three-pointed star, the points being respectively north, southeast and southwest. Like those below, this lake is the centre of an amphitheatre and its rim is the loftiest mountain seen from Denver.”

Bierstadt having completed his color study of a section of the mountain and a sketch of the whole, they then turned their sights upward toward the summit of the highest unnamed snowy peak in the group, which stood more than 2,000 feet above them. Upon reaching the mountaintop several hours later, after an extremely tedious and laborious ascent, they stood upon one of the loftiest points in the country. They were rewarded with a vast panorama of mountain, valleys, and plains that spread out before them. Byers recorded the sight thus:

“Hundreds of snowy peaks, vast ranges stretching away until lost in the dim distance; lakes, deep set in everlasting solitudes; interminable forests, and the illimitable plain were taken in at one sweep of the eye. To the south-ward is Pike’s Peak, and beyond it, dim in the smoky haze, the lofty summits of the Sangre-de-Christo range. In the southwest rise the Sawatch chain, with their rugged sides and pinnacled peaks. Directly west is the picturesque Blue range, between that river and the Piney. Farther to the north-ward are the Rabbit Ears, while stretching to the northward and winding away to the west and southwest is the main chain of the Sierra Madre, or the Rocky Mountains – the great Snowy Cordillera. Below on the southwest is spread out the South Park, every nook and corner of it visible. Even houses could be distinguished with the naked eye, and a powerful glass brings out every minutia. The Middle Park is also in plain view, though intervening mountains bide the deepest or central portion of its basin. Eight or nine miles southeast are a cluster of lakes, probably the source of a branch of Montana Creek. The Olatte and its tributaries, with all their meanderings, can be clearly traced for a hundred miles outside the mountains.”

John Fielder’s photo of Mount Evans from Chicago Lakes, Mount Evans Wilderness, 1998.

Courtesy John Fielder

Bierstadt suggested this nameless glorious peak upon which they were standing be christened “Rosalie” for the wife of his traveling companion, Fitz Hugh Ludlow. This certainly was a grand romantic gesture as well as a glimpse of things to come – in a few years, Rosalie Osborne Ludlow would become Mrs. Albert Bierstadt upon her divorce from Fitz Hugh Ludlow.

Bierstadt hastily sketched the panorama before him as a bitterly cold wind blew down from the northwest and would soon force them to head down. They camped at Summit Lake that evening and continued their descent on June 20, encountering a blinding snowstorm such as Byers was accustomed to seeing only in the winter. Upon retiring for the evening, they discovered their blankets were encased in ice. Despite the snow and cold, Bierstadt busied himself with sketching the surroundings from various points.

In the afternoon of the 21st, after Bierstadt completed his drawings, they headed home in an attempt to outrun the storm brewing on the high peaks, which looked to be more serious than the daily afternoon snow squalls they had previously encountered. With the exception of two or three stops for sketches, they pushed on as rapidly as possible to avoid the storm, but were unsuccessful. Before long, snow, hail, and rain overtook them. Cold and wet, they were greatly relieved when they eventually reached Central City that evening and the next day traveled to Denver dry and rested.

In the five days spent on their journey, “Mr. Bierstadt worked industriously during our stay, making sketches in pencil and studies in oil – these later in order to get the colors and shade,” Byers recalled, continuing, “Mr. Bierstadt obtained a great number of valuable studies in colors, and drawings. He was in ecstacies with the scenery, pronouncing it the finest he has ever found, which is certainly a high enconium, considering that he has spent three years among the mountains of Europe; is familiar with the Alps throughout their length, and also with all the mountains of the eastern states.”

Upon his return to New York later that year, Bierstadt, using the Colorado sketches, began working on his “great Rocky Mountain picture.” He completed “A Storm in the Rocky Mountains, Mount Rosalie,” in 1866, the same year he married the woman he loved and had named the peak after. This oversized masterpiece easily captures viewers and draws them into the dramatic and grand effects of nature – the brooding valley in the foreground, the sunlit lake, and the turbulent storm brewing on the distant peaks.

The name Mount Rosalie became well-known for this peak, and in 1866 botanist Charles Christopher Parry listed Mount Rosalie on his roster of peaks ascended and measured. In 1869, Professor W. H. Brewer pointed out Mount Rosalie on his list of peaks seen from Grays Peak.

A Colorado legislative excursion early in 1872 set in motion the idea of changing the name of Mount Rosalie when territorial politicians embarked on a train trip to Greeley in celebration of the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad, which Governor Evans had been instrumental in helping establish. Greeleyites turned out en masse. The Rocky Mountain News reported that “upon the suggestion of Rev. Mr. Adams of Greeley, a mountain near the Chicago Lakes was christened Mount Evans, and the governor all blushes and embarrassment, accepted the honor and hoped it would be a very prosperous mountain!”

The Hayden Survey of 1874 listed Mount Evans along with Mount Rosalie.

Colorado’s Highest

It is not clear which peak the Rev. Mr. Adams had in mind, and so the name Mount Evans came into use along with Mount Rosalie. A new name may be given to a peak; however, a long-standing one is difficult to remove. The Hayden Survey report for 1873-74 lists Mount Rosalie and adds Mount Evans as peaks above 14,000 feet.

The 1881 Hayden Geological and Geographical Atlas of Colorado has both peaks marked and again both above 14,000 feet, with Mount Evans in its current location and Mount Rosalie a few miles to the southeast – the current location of Rosalie Peak today. Perhaps these names weren’t affixed to the correct peaks, and this confusion caused an error in the triangulation, giving the present-day Rosalie Peak an elevation greater than its actual height.

To muddy matters even more, the US Geological Survey (USGS) says that Bierstadt gave the name Mount Rosalie to the peak that is now the present Mount Bierstadt and the name Monte Rosa to what is now Mount Evans. The name Rosalie often appeared on different maps of the time as “Rosa” or “Rosalia.” It is extremely difficult to know exactly which peaks received which names back in 1863 and through the years, but what is certain is that the name Rosalie was chosen out of love and devotion to honor Albert Bierstadt’s soon-to-be wife.

In December 1894, 22 years after the Rev. Mr. Adams’ unofficial christening of Mount Evans, Mrs. Frederick J. Bancroft of the Denver Fortnightly Club “presented the matter of having the name ‘Mount Evans’ (sometimes improperly called Mount Rosalie) made legal by our next legislation and moved that the numbers of the D.F.C. sign a petition to that effect – motion was carried.”

John Evans

colorado.gov

The minutes of the January 23, 1895, meeting of the D.F.C. reflect that the membership had indeed signed the legislative petition to make Mount Evans the legal name and noted that “the D.F.C. has for several years used a sketch of Mount Evans on its yearly programs.” It was thought that the petition and legislation was “done as much in honor of our first president as our Territorial and State Governor.” Mrs. E.M. Ashley concurred and “thought it also a deserved honor to the governor’s wife, Mrs. Evans – who was the first president of our club.”

Mr. William N. Byers was a guest at the January 23 meeting to tell his tale of accompanying Bierstadt on the sketching trip and the naming of Mount Rosalie. In spite of Mrs. Bancroft’s motion, petition, and ratification of the legislative resolution to have the name changed, Mr. Byers’ fondness for his artist friend caused him to still wish the name Mount Rosalie might be retained.

In the Tenth Session of the General Assembly of the State of Colorado, January 2, 1895, Senator James F. Drake introduced Senate Joint Res. 15 in response to the D.F.C.’s petition. The resolution read:

“Be It Resolved. By the Senate and House of Representatives of the General Assembly of the State of Colorado, in view of the long and eminent services to the State of ex-Governor John Evans, and as a fitting recognition thereof, that the mountain situated in what is known as the ‘Platte Range’ in section twenty-seven (27), township five (5) south, of range seventy-four (74) west, be, and the same hereby is named in honor of the ex-governor, and shall hereafter be known and designated as ‘Mount Evans.'”

Governor Albert W. McIntire approved the bill on March 5, 1895, and the D.F.C. sent an embossed copy of the act to Governor Evans in honor of his 81st birthday on March 9, 1895. At the D.F.C. meeting later that month, the president read a letter from Mrs. Evans thanking the club, at the request of her husband, for the beautiful testimonial presented informing him of the legal naming of Mount Evans.

The name may have changed legally, but the name Mount Rosalie remained on maps, with its height listed above 14,000 feet, for the next few years.

A 1901 Denver Post article lists both Mount Evans and Mount Rosalie as above 14,000 feet. As methods of measurement and mapping became more accurate, Mount Rosalie’s height was determined to be less than 14,000 feet, and the name was changed from Mount Rosalie to Rosalie Peak, which is its name today.

In recent years there has been some talk of changing the name again and having Mr. Evans’s name removed from the grand peak due to his involvement in and attempt to cover up the Sand Creek Massacre that resulted in his resignation as governor. At this date, nothing official has come of it.

Overshadowed by the fame and beauty of the Front Range Mount Evans is a second Mount Evan (or Mount Evans B, as it is commonly called) residing northeast of Leadville and two miles from Mount Sherman in the Mosquito Range. This 13,577-foot Mount Evans mostly likely gained its name from the early miners in the 1860s, when John Evans was Territorial Governor, and the name became fixed on maps thereafter. Local residents often named the geographical features surrounding them. This was especially true in the mining regions as these features were key landmarks in the staking of mining claims and the creation of early maps.

While with the Hayden Survey in 1876, chief topographer A.D. Wilson performed fieldwork for the topographic map of Leadville, including the surrounding mining district. The locally used name of Mount Evans for this particular peak was placed on the Leadville and Mosquito Range topographic maps that were published before the official designation of the Front Range Mount Evans in 1895.

In September 1916, Roger Toll, of the Colorado Mountain Club, wrote a letter to the United States Geographic Board requesting a change of name for this peak:

“The confusion with the peak of the same name in the Front Range, 14,260 feet, seems undesirable, but if the name of either is to be changed it should be the one near Leadville since the name Evans has been prominent in the history of the state and should be retained by the more important of the two peaks, namely that in the Front Range to which the name is already established.”

Nothing came of Toll’s request, and three years later, in October 1919, a letter from the Colorado State Highway Commissioner to the National Geographical Society requested they “please put us on your mailing list for your rulings and bulletins regarding geographical names in Colorado which we need in the preparation of Progressive Military Maps, and suggest that the name of Mount Evans near Leadville be changed because we have one near Denver which has the best title.”

The U.S. Geographic Board then sent an inquiry to the Leadville Postmaster in November 1919 requesting information as to the use of the name Mount Evans. In response to the questions presented, Postmaster M.J. Brennan stated:

“The name first originates in Prof. F.S. Emmons’ U.S. Geological Survey of the Leadville Dist. As reported in Monograph XII published in 1886, Mount Evans lies at the head of the Evans amphitheatre and Evans gulch frequently mentioned throughout the works of Prof. Emmons and to change this name would lead to great confusion in the reading of his works, which are the Leadville mining man’s bible.”

johnfielder.com

The name did indeed remain for this mountain, and although today there are two peaks with the Mount Evans designation in the state, there isn’t any confusion as to which one is “the Mount Evans.”

Excerpted with permission from Colorado’s Highest: The History of Naming the 14,000-Foot Peaks, by Jeri L. Norgren, with 1870s Hayden Survey Sketches, photographs by John Fielder and oil paintings by Robert L. Wogrin. Available at local bookstores, as well as johnfielder.com.