Monika Swiderski

Audio By Carbonatix

Colorado is at a crossroads. Again.

Back in 1833, brothers William and Charles Bent, along with trader Ceran St. Vrain, built a fort on the north side of the Arkansas River, the border of a territory claimed by both the United States and Old Mexico. Bent’s Fort quickly became a busy trading post frequented by trappers, travelers, members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes, and the U.S. Army.

And for the most part, everyone got along.

“It is seldom that such a variety of ingredients are found mixed up in so small a compass,” wrote Josiah Gregg, who visited the fort in 1847 and described in his journal what he found there — a wide range of people speaking a number of languages, but communicating effectively and peacefully.

For sixteen years, the fort was the only major stop on the Santa Fe Trail between Missouri and the Mexican settlements. But, beset by disease and other disasters, it was abandoned in 1849 by its founders, who went on to start other trading posts in the increasingly conflicted territory.

Experts study the remains of the fort in the 1960s.

History Colorado

Its significance remained, however. In 1960, Bent’s Old Fort became a National Historic Landmark, and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

Over 140 years after the trading post was founded — and just in time for the U.S. bicentennial and Colorado’s centennial in 1876 — the National Park Service led the charge to reconstruct Bent’s Fort as it had looked in the 1840s. The crew used contemporary sketches, paintings and diaries like Gregg’s to recreate the replica on the original grounds of the trading post outside of what had become La Junta, turning piles of disintegrating adobe walls into a new Bent’s Old Fort, a major tourist attraction and economic driver for southeastern Colorado.

Fifty years ago, it reminded Americans that history was not all about tall ships and Civil War battlegrounds.

Tourists would travel hundreds of miles to catch re-enactments at the fort, watch birds in the wetlands along the river, shop in the gift shop (after the dedication of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in 2007, I ran into Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell there, looking at a display of his jewelry), and get a feel for how people had lived decades before Colorado became a state.

There was just one problem: This fort was not made to last, either. Today, the adobe is crumbling, taking history down with it. The site is in such bad condition that the NPS wrote the Colorado State Historic Preservation Office early last year to suggest that the complex be deemed “a non-historic structure” that was “ineligible for the National Register of Historic Places.” In the meantime, the NPS closed much of Bent’s Old Fort to the public over safety concerns, allowing visitors to visit only the plaza in the center of the structure and take an occasional tour carefully guided by a ranger.

Parts of Bent’s Old Fort are now closed to the public.

History Colorado

As state historians considered Colorado’s next big event, its 150th anniversary this year, such a poor national assessment was not acceptable. Representatives from the State Historic Preservation office made a site visit to the fort last March, and determined that the site is “fixable.”

“Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site is an important cultural and economic touchstone in southeastern Colorado,” says Dawn DiPrince, History Colorado CEO, State Historic Preservation Officer and a native of the area around the fort. “It is an essential historic site in the large American story.”

And that story gets more complicated by the minute.

What’s Old Is New Again

The year after Bent’s Old Fort site became a National Historic Landmark, an East Coast family picked up and moved to Colorado so that the kids could grow up in the country. Their mother, Elizabeth “Bay” Arnold, was reading a book about Bent’s Fort at the time, saw a drawing of the original trading post and told her ad-man husband, Samuel, that they should “build an adobe castle like this,” recalls daughter Holly Arnold Kinney.

The Arnolds found a beautiful property nestled in the red rocks of Morrison and bought it in 1961.

They hired William Lumpkins, an adobe expert working in Santa Fe. Lumpkins pulled together a crew to create over 80,000 mud and straw bricks on-site, then turned them into a replica of Bent’s Old Fort, only slightly scaled down for size. It was an ambitious project — too ambitious. As Holly remembers, costs rose so high that the bank suggested the family put a business in the building they’d created as their home, to help cover costs.

So Lumpkins redesigned the lower level to hold a restaurant, and The Fort opened in February 1963.

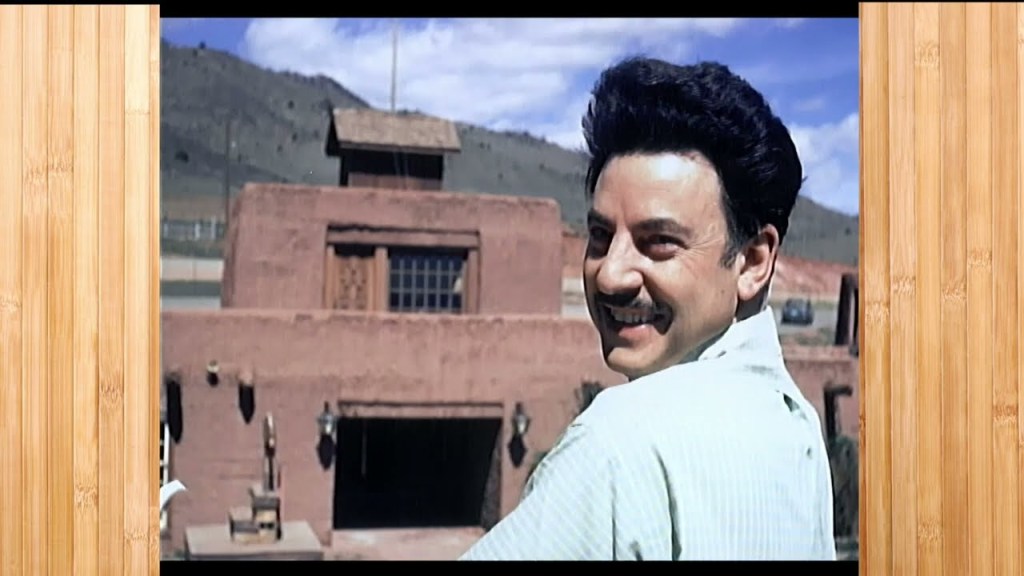

Sam’l Arnold turned the Fort restaurant into a major attraction.

The Fort

The menu was just as historically accurate as the structures. The Arnolds read those old diaries, too, and recreated the sort of foods earlier travelers might find when they visited the trading post, fare that combined Native American ingredients (Julia Child loved the buffalo bone marrow) and Mexican dishes, washed down with whiskey complete with gunpowder. As Samuel became more invested in his research, he lost a few letters in his first name (shifting to Sam’l), wrote the cookbook Eating Up the Santa Fe Trail, then wrote more books and starred in TV shows about foods of the frontier. Walking through the Fort in old-timey gear, Sam’l would play the mandolin and issue his standard mountain man greeting: “Waugh!”

The Fort soon became a must-stop for any visitor to Denver. But over time, this Fort, too, went through challenges. At one point, the Arnolds sold it, but Sam’l took it back, with Holly in line to continue running it; she was becoming a force in the state’s tourism industry, too. Meanwhile, the restaurant made its own history: Always popular with visiting celebrities, it served world leaders in 1997 for the Summit of the Eight (a helicopter pad remains as a souvenir of that event that brought everyone from President Bill Clinton to Tony Blair to Boris Yeltsin to Denver). And in 2006, the year Sam’l Arnold passed away, this Fort was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

According to the National Park Service assessment, “This two-story Pueblo Revival building is exceptionally important at the state level of significance for its rendition of traditional adobe construction and an architectural form that not only reflects Colorado’s rich heritage but is built according to the original 19th century plans for the construction of Bent’s Fort…”

By last year, though, Holly was ready to move on. On January 6, she sold the Fort to Revesco Properties and City Street Investors for $4.5 million; the new owners also have a deal to purchase fifty adjacent acres.

“It came out of the blue,” recalls Joe Vostrejs, CEO of City Street. He’s sitting in the second-floor hallway of the Schoolyard, the rejuvenated Evans school that City Street restored, then opened in the spring of 2025

Holly had made the decision to sell the restaurant that sits on an eight-acre parcel, as well as the fifty-acre parcel right below it, as a package, and that helped lead to the partnership. “A land developer doesn’t want a restaurant, and a restaurant guy isn’t going to want land,” explains Vostrejs. He’s technically the restaurant guy, although he left that industry at 26 to go into real estate for two decades, then became integral in the resurrection of Larimer Square as well as the renovation of Union Station. With City Street, he’s acquired restaurants and opened beer gardens across the metro area.

Revesco’s Rhys Duggan, who envisioned the River Mile along the Platte River before Kroenke Sports & Entertainment shouldered that entire project, is the land guy. “We went out, we toured, we met with Holly, we went back and forth,” Vostrejs recalls. Ultimately, they couldn’t resist the deal. “It’s a fabulous piece of Colorado history,” he says.

And as he and Duggan discovered, it’s in pretty fabulous shape, because the Arnolds had taken such care with its initial construction. “Like any old building, you’re always doing renovations and repairs. It never ends,” Vostrejs admits. But it helps that Holly stayed in touch with adobe experts who could supply replacement bricks as needed. While the new owners have plans for updating equipment, the building itself is sound.

Still, while preserving the past is important, Vostrejs recognizes that the Fort won’t survive if it doesn’t stay current.

“All those little pieces of history,” he says. “When you think of Denver Union Station, even something as small as Billy’s Inn, it’s important to take these old places and make them really relevant. The Fort is still a very successful business. I think we have an opportunity to sustain it as it is, while at the same time opening it up to a new generation.”

The Fort restaurant has stood strong through all kinds of weather.

The Fort

That involves not just offering different menus in different parts of the restaurant, but livening up the courtyard and finding other ways to use the space, both daily and for special occasions. “Follow the same principles as at Union Station, Larimer Square,” Vostrejs says. “Make it as accessible to people as possible. Give them as many excuses to use it as possible…

“We love the historic fabric and character,” he concludes. “The issue is making them relevant to today’s audience. That’s our job…to thread the needle.”

And then tie that thread back to the original inspiration.

Holding Down the Fort

When the History Colorado Center opened at 1200 Broadway in 2012, one of its initial exhibits was dedicated to Bent’s Old Fort. Responding to criticisms that the display took a cartoony, stereotypical approach to the Indigenous people who frequented the trading post, the display soon underwent significant revision.

(Not as significant as Collision, the original exhibit devoted to the Sand Creek Massacre, however. After tribal descendants complained, Collision was ultimately removed altogether and a new display created, done in consultation with the tribes and offered in their own languages. It was finally installed in 2022, 158 years after 250 members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes camped on the banks of the Big Sandy were killed by volunteer troops led by Colonel John Chivington.)

The staff of History Colorado has changed, too: DiPrince, who started at History Colorado in 2012, was moved to the top job from her role as COO five years ago. She’s led the charge to make this state’s history not just more accessible but more inclusive, “a history that belongs to all of us.” DiPrince says.

Growing up in LaJunta, she was a frequent visitor to Bent’s Old Fort in the ’80s. Her siblings worked there; she learned to make jerky there. John Carson, descendant of the legendary (and controversial) Kit Carson, a frequent visitor to the original fort, was her teacher and coached basketball with her father; he also worked at Bent’s Old Fort.

Now, more than ever, DiPrince recognizes the importance of the site’s economic impact on the area, and that it’s “so much a part of the community identity.” But it’s also part of Colorado’s identity, she notes, as well as “an important part of the multicultural history of the state.”

Bent’s Old Fort is a popular tourist attraction in Southeastern Colorado.

NPS

So when the NPS suggested that the 1976 version of Bent’s Old Fort was a “non-historic structure,” DiPrince was just the person to point out the importance of the site, particularly as the state and nation prepare to celebrate two big anniversaries. While President Donald Trump’s America 250 commission has focused on fireworks and hats, History Colorado is pushing an assortment of projects, including major exhibits at the center as well as other displays at its facilities around the state; it’s in the process of collecting 150 oral history accounts from residents around Colorado, while communities are sharing their own celebrations on a state website.

Some of those communities were jarred at the end of December, when Trump vetoed funding for the Arkansas Valley conduit, a sixty-year-old project geared to providing clean water to all the Coloradans living along the Arkansas River that flows past Bent’s Old Fort. But politicians are hopeful the president’s decision will be reversed by Congress.

And soon, DiPrince hopes she’ll be able to share that Bent’s Old Fort’s status is back on track, too. After her agency’s fact-finding mission, the NPS determined that the fifty-year-old replica was eligible for designation, after all. “At this point, it needs a really good maintenance plan,” says DiPrince.

And if the NPS can’t take a clue from the Fort restaurant, History Colorado also has an adobe expert who can help. “We work with adobe all the time,” DiPrince says. “There’s work to be done, but it’s not beyond repair.”

Colorado may be at a crossroads, but as history has shown, it usually moves in the right direction. Nothing is beyond repair.