CBS News via YouTube

Audio By Carbonatix

Nineteen years ago, on April 20, 1999, an attack on Columbine High School killed twelve students and one teacher and injured 21 others. The legacy of this terrible event continues to echo, enhanced by the reaction to February’s massacre at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, epitomized by school walkouts planned across the country for today, and the continuing efforts of Safe2Tell, a Colorado organization that’s become a national model for preventing school-related cataclysms of all sorts, from shootings to suicides, by encouraging students to anonymously reveal what they know.

“I have seen so many unspeakable tragedies involving children, and always could see that in hindsight we could have done something to prevent them,” says Susan Payne, Safe2Tell’s founder and executive director. “Why did I do this? I guess it comes down to the fact that I don’t want bad things to happen to our children when there are adults standing by who are ready to help – when all we need is that piece of the puzzle to connect caring, committed adults at the local level to children that need their support or intervention.”

Today, Safe2Tell is a state agency under the Colorado Attorney General’s Office, and it’s got national clout. Since Parkland, Payne has met or conferred with representatives from dozens of states interested in developing or improving similar programs by following the template that she established. But its beginnings actually predate Columbine and flow from Payne’s background in public safety.

Safe2Tell executive director Susan Payne.

“I’ve been in law enforcement for 28 years,” she says. “My father was in law enforcement, too, and my uncle was Lou Smit, who was called in to do the JonBenét Ramsey investigation. I was an engineering major and worked at the fire department as an EMT – but then I decided I wanted to be a police officer. I took the test and got on with the Colorado Springs Police Department. But I don’t know if I was as prepared as I thought I was for the things I would see. A lot of it was unspeakable.”

Along the way, Payne became a school resource officer, “and I focused on being very proactive about educating children to keep them safe, sort of like I was taught. Take Ted Bundy: He was a great-looking guy with all the charms, but he was also a violent, homicidal killer. So I tried to teach kids how to keep themselves safe and taught them about strategies like strength in numbers and how important who they connect with is. When 100 kids showed up at a field for a fight, that meant 100 kids knew there was going to be a fight, but none of them told an adult.”

In 1997, Payne started a prevention-oriented pilot program in the Pikes Peak region – the precursor to Safe2Tell. But even after the Columbine killings, her creation didn’t immediately branch out.

A Safe2Tell graphic about cyberbullying from the Safe2Tell Facebook page.

“The first thing Colorado did was launch a safe-school hotline, which I think is important to bring up, because that’s what every place around the country is thinking of doing now,” Payne stresses. “But after two years, the state realized the hotline had minimal use – less than seven reports. What was needed was early interruption and being more aware of the situations you’re surrounded by every day. And we needed to build a statewide infrastructure where that situational awareness existed, whether it was in elementary schools, intermediate schools or high schools.”

The Pikes Peak program had all these attributes, albeit on a smaller scale. “We were able to demonstrate that we’d stopped 234 incidents of violence,” she recalls. “And the need for what we were offering was clear when we made a deeper study of the Columbine tragedy and we were able to see what went wrong. Information wasn’t being shared between schools and law enforcement, and there was a real need for a proactive method of communication and an infrastructure that connected law enforcement and multi-discipline school teams in a system of accountability.”

Just as important, she continues, “we needed to break through the mindset of young people – to let them know, ‘We’re listening to you. And this is a tool for you to tell us what you know.'”

In 2003, the framework for Safe2Tell was put in place under the auspices of Crime Stoppers, with the Colorado Trust providing a seed money grant; Payne was appointed director. The program was incorporated as a nonprofit in 2006, with Payne becoming its executive director. Three years later, she added the title of the first special agent with the Colorado Department of Public Safety-Homeland Security, and by 2014, Safe2Tell had transitioned from a public-private partnership to an operation under the Colorado Attorney General’s office.

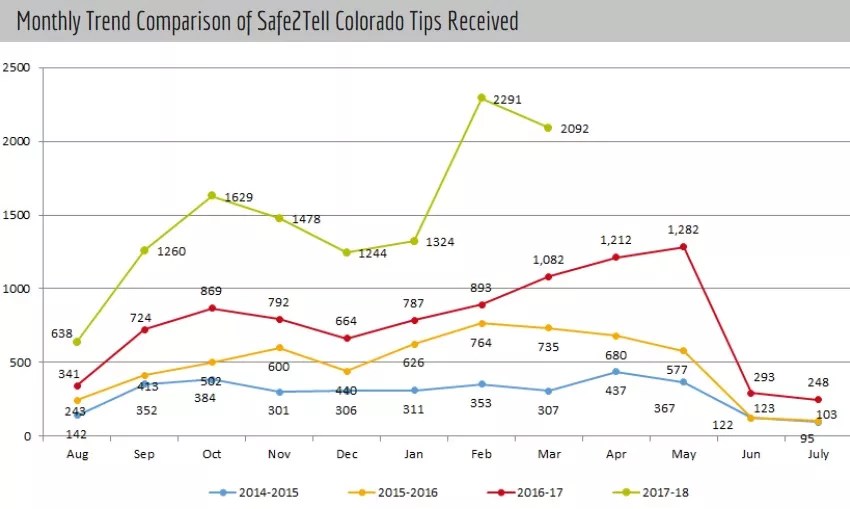

This graphic shows how the number of tips received by Safe2Tell has mushroomed over its years of operation.

Over that stretch of time, student reports to Safe2Tell increased thanks to aggressive outreach efforts and the realization that the anonymity of those making reports really would be protected. But the numbers truly mushroomed three years ago, with the introduction of a mobile app (get it here). It’s now commonplace for Safe2Tell to receive more than 1,000 reports per month, and of late, that digit has more than doubled.

Potential school attacks accounted for the largest percentage of reports in February, when the Parkland shooting took place. Out of 2,292 reports that month, 295 of them dealt with the possibility. But new data for March shows that this was an anomaly. Last month, 330 of 2,092 reports received concerned suicide threats, followed by drugs (234) and bullying (201), while concerns about an attack at schools fell to 134 – just seven more than the 127 reports about cutting.

To Payne, these figures are a key to Safe2Tell’s success. “We’ve had other states say, ‘We only want to take serious threats,'” she says. “But what the research shows is that the opportunity to intervene and interrupt concerning behavior is just as important for a lower threshold event. That’s where we want people to make a cultural shift. And a lot of these things can be precursors to more serious actions. If someone is being cruel to an animal, that’s significant, and an indicator of violent behavior. Can we agree there needs to be an interruption and an assessment of that? Yes.”

Over the years, she adds, “suicides have become our most reported occurrence, and I think that’s reflective of changes in schools about the importance of social and emotional learning and caring for the whole student. Suicides are a huge concern and, most often, they can be prevented. We also get a lot of reports about depression and self-injury, and if you combine those categories, many of them are proactive mental-health concerns that we can do something about.”

Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi quizzed Colorado Attorney General Cynthia Coffman about Safe2Tell after the Parkland shootings.

Courtesy of the Colorado Attorney General’s Office

Intervention doesn’t necessarily stop at the state line, either.

“The online method of reporting has really become a significant feature because of the ability of young people to send images, screen shots or videos – and that’s what happened in one case of kids who were playing an online video game,” she explains. “One of the players asked, ‘Will you guys be on tomorrow night?’ and another one answered, ‘I may not be, because I may be dead. You’ll hear about a massacre at my school. I haven’t decided if I’ll kill myself or have the cops do it for me.’ Someone sent in that screen capture to Safe2Tell, and it led us to a house in Biloxi, Mississippi – and law enforcement was able to make an arrest and take weapons and computers. The student said he wasn’t really going to do what he said he was going to do, but that’s still an interruption of behavior and something we track when we look at what’s been averted.”

Payne’s work hasn’t gone unnoticed. “I’ve been invited to the White House on three different occasions, always post-tragedy,” she says. After Parkland, her phone has been ringing even more frequently. She’s been in regular contact with staffers for Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi, who’s also met with Colorado AG Cynthia Coffman about improving school safety, and she’s recently spoken with counterparts in states such as Arizona, Louisiana, Nevada and more.

“I definitely see the pendulum swinging to people seeking solutions and proven strategies that work,” Payne concludes. “And Safe2Tell works.”