Audio By Carbonatix

Given how ubiquitous it is around these parts, Coloradans can be forgiven if they’ve forgotten – or just never noticed – the cultural impact of Coors Banquet Beer.

Some touchstones are obvious: all those commercials voiced by cowboy character actor Sam Elliott over the years or, say, the entire plot of Smokey and the Bandit. But Banquet beers have also been look-quick-or-you’ll-miss-it additions to countless other films. The title character gets fall-down drunk off ’em in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Mel Gibson’s Sergeant Martin Riggs gets a little luckier and keeps his footing when he drinks them in Lethal Weapon, though perhaps not as lucky as Dustin Hoffman’s character in The Graduate, who sips one while drifting in a pool immediately after, well, you remember. Isaac Hayes savored a Banquet on screen in Truck Turner, Marilyn Monroe tipped them back backstage while filming The Misfits, and Paul Newman was rumored to require them on all his movie sets. Fans of more modern entertainment can look to Netflix’s Cobra Kai, Paramount’s Yellowstone and HBO’s Winning Time; Coors Banquet Beer pops up in all three in a rare moment of common ground amid the streaming wars.

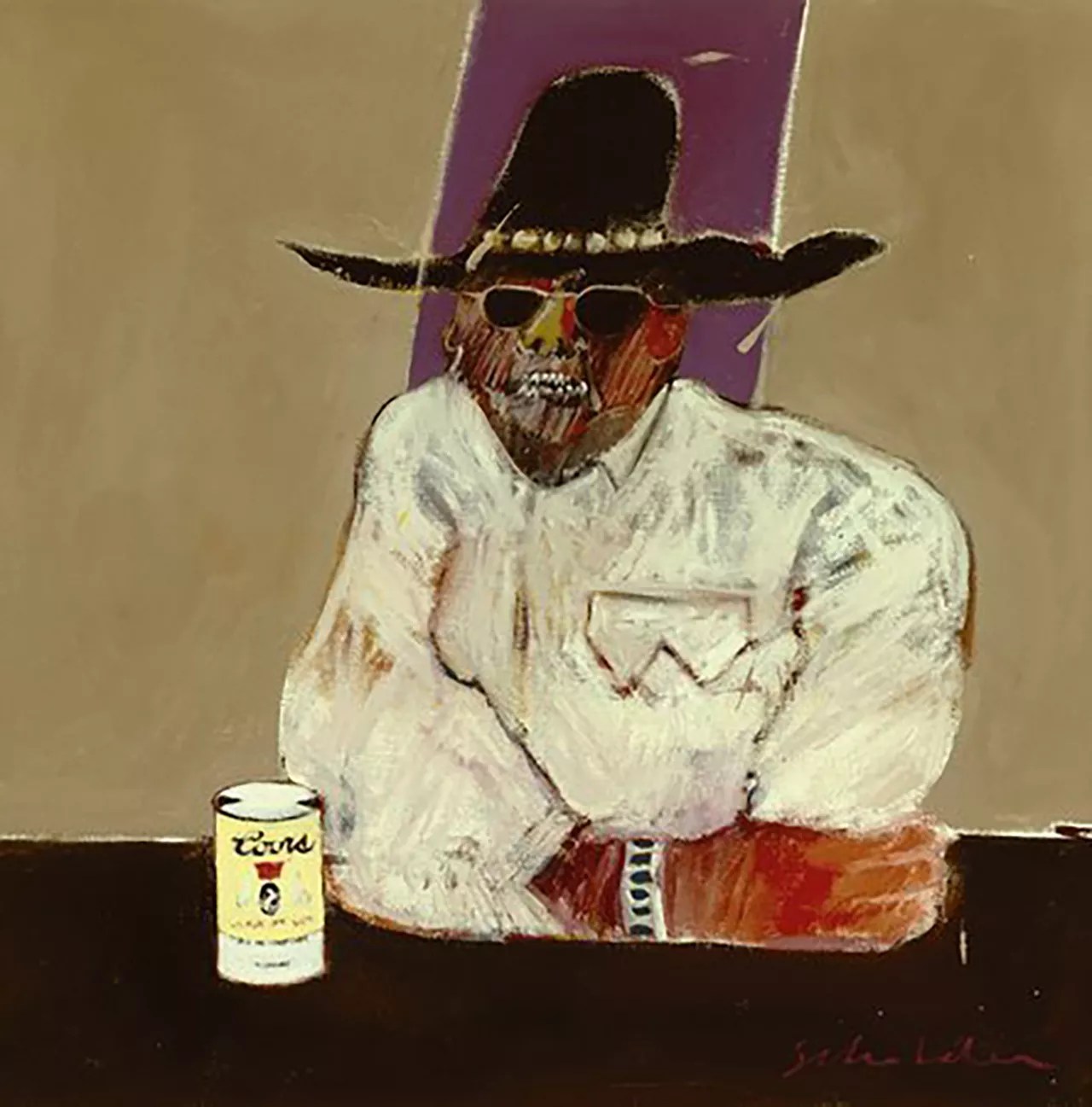

Fritz Scholder’s 1969 “Indian With Beer Can,” 24 x 24 inches, oil on canvas.

Collection of Ralph and Ricky Lauren/Photo by Bill McLemore

While Coors Banquet usually appears as background, it’s done so across media and history in a way that suggests it’s more than a prop. For fine-art connoisseurs, it gets top billing in Fritz Scholder‘s 1969 “Indian With Beer Can,” which Smithsonian curator Paul Chaat Smith called “easily the greatest and most influential painting in the history of Indian art.” Music lovers will notice it on the album cover for Neil Young’s seminal On the Beach – even if on-again, off-again bandmate David Crosby claims on Twitter that he didn’t touch the stuff. Long before Coors Banquet was available nationwide, President Gerald Ford was rumored to have secreted some away on Air Force One after a ski trip to Colorado; President Dwight Eisenhower and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger purportedly did much the same.

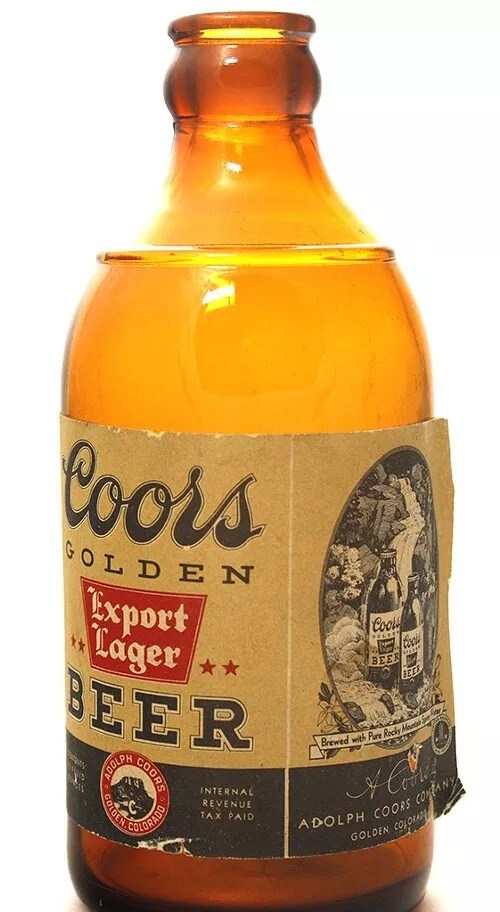

What’s most striking is that all those beers in all those movies and in that painting and in the presidential luggage compartment look a whole lot like the Coors Banquet you could pick up at a liquor store or order at a bar today. That’s intentional: Whether by can or by bottle, Banquet has been delivered since at least as far back as the 1930s with key design elements that “we’ve never wavered from,” according to Stephanie Clanfield, the global marketing manager for Coors Banquet Beer at the Molson Coors Beverage Company.

A Coors can from the ’40s.

Molson Coors

Some of those elements are impossible to miss. The cans, the labels, the beer carriers and the cases are yellow. As Brett Whitley, a 24-year-old clothing designer from Georgia puts it, “If you see someone drinking a yellow can, even if there’s a koozie or brown bag over it, you know it’s a Coors.” Ryan Pelton, a 32-year-old furniture installation manager born and raised in Colorado Springs, agrees: “If I’m at a bar and I want to make sure the bartender gives me the right beer and not a Coors Light, I ask for the yellow can.” And according to Molson Coors Golden archivist Heidi Harris, “The most recognizable trait of a Coors Banquet can or bottle is the yellow or ‘gold’ labels.”

So is it yellow or gold? “We call it our ‘buff yellow’ color,” says Clanfield. But University of Colorado football fans can settle down: While there’s more than a passing resemblance between the color of a Coors can and the gold on the team’s uniforms, they are different – and CU didn’t make a buffalo its mascot until 1934, some 61 years after Adolph Coors set up shop in Golden.

Why yellow (or gold) at all? “You know, it’s something that I’ve asked the archivists about before,” Clanfield recalls. “I wish I had an answer, and I feel like there might be some tales out there, but I don’t have the true history on how they landed on yellow.”

Some things are simply unknowable. What we do know is that the color inspired numerous nicknames, such as “yellow jackets,” as the cans are referred to on Yellowstone. The sobriquet pre-dates the show. Alex Piper, a thirty-year-old software sales consultant, drank the stuff in college before she moved to Colorado in 2015. “We liked Coors Banquet because Georgia Tech’s sports teams are the yellow jackets, so that’s what we knew to call them when we ordered them,” she remembers.

“Yellowbelly” is another common nickname, and fans often get even more creative. “I like to go with the ‘CB smoothie,'” says Pelton with a laugh. “If the bartender looks at me funny, then I’ll go further and say, ‘I’ll take the buckskin.’ If they still don’t get it, I’ll say, ‘I’ll take a Coors Banquet.'”

Adds Whitley, “I’ve heard it called Colorado Kool-Aid, which is charming. But when I’m visiting Colorado, I just say ‘Banquet.'”

Confirms 42-year-old concrete contractor Micah Bloom, who grew up in Golden, in the shadow of Coors, the largest single-site brewery in the world: “A Banquet. I’ll take a Banquet.”

The Coors Brewery in Golden got its start in 1873.

Denver Public Library

The word “Banquet” first appeared on packaging in the 1930s, according to Harris, but Banquet was likely shorthand for Coors long before the company made it official. After all, Coors dates to 1873, when mining was Colorado’s most significant industry – and Golden was a hardscrabble town on the edges of polite society. If you believe the legend, Clear Creek Canyon miners would drink a few after work to celebrate the end of a long shift in the mine, sometimes in a banquet hall or banquet tent. “It was dubbed good enough to be served at a banquet, hence the Banquet name,” Harris says, before soberly noting that “we can’t confirm the origin or accuracy of this story.”

A good myth can be more fun than the truth, especially when you’re drinking. But there are some verifiable Coors facts in the historical record, even if they seem like tall tales. Today the aluminum can is far and away the most popular way to drink beer across the globe. According to a January 15, 1959, article in the Colorado Transcript, it was then-chairman Bill Coors who engineered the first commercially viable aluminum can for Coors, an invention that would come to revolutionize the entire industry and lead to significant societal leaps in recycling.

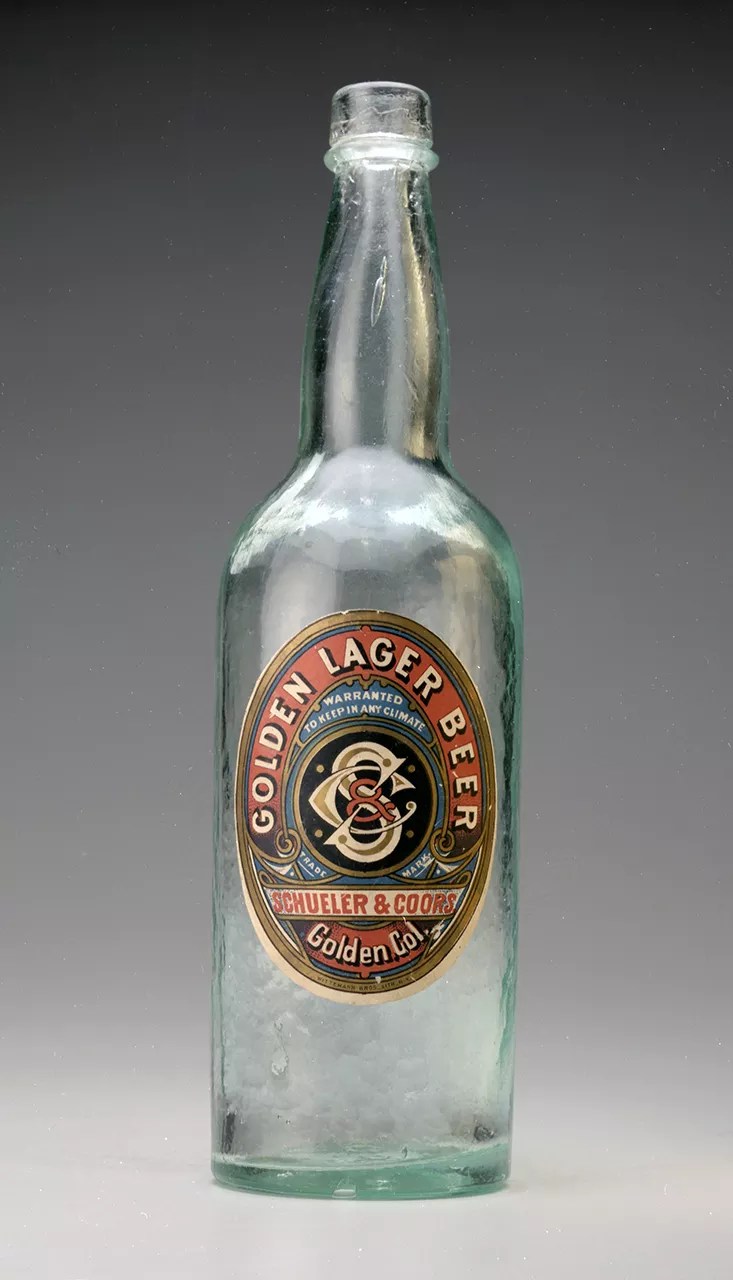

An original stubby Coors.

Molson Coors

That wasn’t the first time Coors tried a new container. In 1936, the company introduced its now-iconic stubby bottle to save on shipping costs and to avoid breakage in transit – which was common with long-neck bottles. The 12-ounce stubby also helped turn consumers on to canned beer, then made of steel, by persuading them that they weren’t getting shortchanged just because the container was smaller; a stubby fit in your hand just about as well as a can.

But initially, the shorter bottles didn’t go over as expected, as advertisements from 1941 highlighted the product returning to traditional long necks. That might come as a surprise to the Coors drinkers of today, who are accustomed to seeing a beloved stubby slide down the bar when they ask for a Banquet. The shorter form returned in 2010, Harris says, “to stand out on shelves, and to celebrate Coors Banquet’s heritage.”

This round, it’s been a hit. “I love the stubby bottle,” Whitley says. “It is such an absurd receptacle to drink out of. Why would you ever make a bottle that size? It looks like something you’d see on a medicine shelf in the 1800s. It’s perfect.”

Whether on bottle or can, the rest of the packaging conveys more history. The two golden lions, or griffins, each with two tails, started appearing on Banquet cans as early as 1937, though similar lions have quietly watched people get drunk for almost as long as brewers have made that possible. They’re a “longtime heraldic brewing symbol,” according to Harris.

“They’re elements that pay homage to the brewers of the past,” Clanfield adds. “They’re always seen protecting the brand, and we treat them in a sacred nature.”

And speaking of nature, there’s the waterfall.

Fish Creek Falls, captured on the Coors can.

Steamboat Chamber of Commerce

Normally nestled next to a tagline emphasizing that Coors is “brewed with 100% Rocky Mountain Water,” the waterfall may also be there to paradoxically remind you that “this is no downstream beer,” a turn of phrase that Coors leaned on in ’80s advertisements.

Unlike the lions, the waterfall is real – though drinkers may not know that.

The guess from Bloom, who grew up not far from the Coors brewery? “I believe it’s up Clear Creek, up Highway 6 out of Golden.”

From Piper, who moved here from Georgia: “Probably in the Rocky Mountains somewhere. I’m going to go with Crested Butte.”

And from Whitley, the T-shirt designer who comes to Colorado whenever he’s following what’s left of the Grateful Dead: “I hope it’s not fictional. To me, this is the waterfall that makes the Coors. This is the beer waterfall. This is where the beer comes from.”

And here you stumble upon one of those rare moments when the truth is more refreshing than even the best myth. As with that “100% Rocky Mountain Water,” you have to go to the source – in this case, Harris, the Coors archivist.

“The picture of the first waterfall on the Coors Banquet label was taken in 1937,” she says. And that waterfall is Routt County’s Fish Creek Falls, just above Steamboat Springs.

You’d think that would be the end of it, but Harris, like any good archivist, is a sucker for accuracy. “In 1978, when Coors Light was introduced, another waterfall was chosen, named ‘Milton Falls’ – at Bogan Flats, near Marble, Colorado,” she adds.

And yes, a mythic waterfall occasionally graces Coors packaging, too. “The third waterfall is an artist’s interpretation of a waterfall,” Harris notes.

Neil Young had Coors on the beach.

Amazon

The design of something as commercial as a beer can or bottle is usually less open to artistic interpretation than, say, a waterfall or a Fritz Scholder painting or a Neil Young record. But like art and nature, it can inspire conversation – whether you’re asking your friends to define a color under the glare of the hot sun and the friendly buzz of a single 5 percent ABV beer, or having a more heated talk at the bar, where you swear you heard the Coors waterfall was near Ouray.

The makers of Coors Banquet want you to have these conversations. That’s why on April 7, they rolled out their Coors Banquet Legacy Collection, three new can designs and a new stubby bottle label that attempt to tell various stories about the beer, from tales of the five generations of the Coors family to the company’s roots in Golden to the “coveted nature” of the product that inspired Smokey and the Bandit and all those other legends – before new production methods allowed distribution to expand to all fifty states.

Cheers!

Molson Coors

“We’re raising a glass to the history of American beer,” Clanfield says of the collection, available now through the end of June. “We dug through the archives, and we looked through a lot of different design elements so that our values and rich history come through on the packaging.”

That motivation may smack of marketing mumbo-jumbo. Then again, so much of our culture has used Banquet bottles and cans to inject a taste of authenticity by borrowing the brand’s history and iconography, moves often propelled by big marketing budgets. Is it fair for the manufacturer to now draw on that same history in an attempt to make a little art, even if the primary aim is to get us to buy something? The debate over art as commerce stretches back even further than the 149-year history of Coors Banquet.

It’s probably best to continue the conversation over a beer.