Audio By Carbonatix

In November 2018, Denver City Council approved a plan to create safe-use sites for injection drug users – an approach that’s proven effective in preventing overdose deaths in Canada and numerous countries around the world. But in early 2019, backlash from media critics and others short-circuited a plan to introduce a bill in the Colorado Legislature that would have allowed such facilities – and a recent court ruling declaring such sites a violation of federal law creates another obstacle to future efforts.

Lisa Raville, executive director of Denver’s Harm Reduction Action Center, thinks that these developments have cost lives – and she’s got the statistics to prove it. Last year was the deadliest year ever for both Denver and Colorado as a whole when it comes to overdose deaths, she reveals.

In 2019, the number of people who died from overdoses in Colorado totaled 1,062. The data for 2020 is only complete through September, but the number of deaths for the first nine months of the year reached1,152.

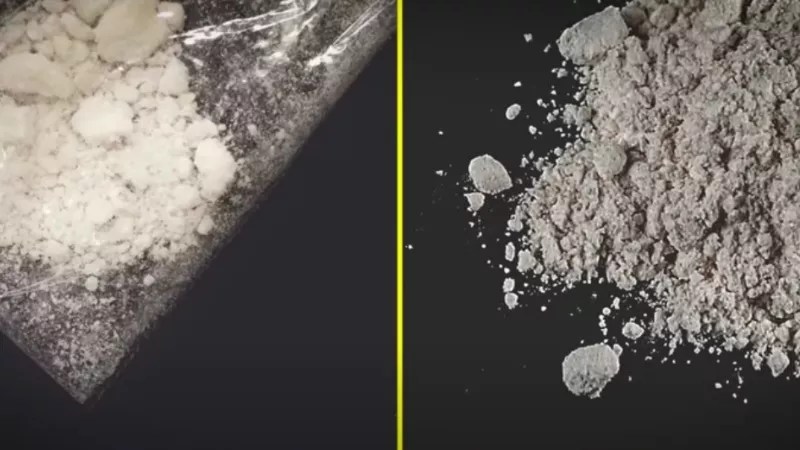

The rise of fentanyl has made a terrible situation worse. The number of people in Denver who died from a fentanyl OD in 2020 was greater than the total number who perished from the same cause in the previous three years, as seen in the following figures:

2017: 18

2018: 17

2019: 56

2020: 119

Overall, Denver suffered 284 drug-related deaths through the first eleven months of 2020. That compares to 201 drug-related deaths in all of 2017, 209 in 2018 and 225 in 2019.

Raville suggests plenty of factors contributing to these statistics, including the greater availability of fentanyl in the state. One new element: fallout from COVID-19.

“We have seen increasing social isolation” as a result of the pandemic, Raville notes, “and if people are using alone, there’s no one there to recognize and respond if there’s a problem.” In addition, she says, “Unhoused folks used to be able to inject in business bathrooms and at the Denver Public Library, where they used to do about fifteen Narcan reversals” – using a drug designed to stop overdose effects – “every year. But now, with library and business bathrooms being shut down, people are overdosing publicly, in places like RTD transit stations. Overdoses are again the number-one cause of deaths for our unhoused neighbors.”

On January 12, a ruling was handed down in the case of the United States of America v. Safehouse, a Pennsylvania nonprofit, by the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. Writing for the majority, Judge Stephanos Bibas, a 2017 appointee of President Donald Trump’s, explained his reasoning:

Though the opioid crisis may call for innovative solutions, local innovations may not break federal law. Drug users die every day of overdoses. So Safehouse, a nonprofit, wants to open America’s first safe-injection site in Philadelphia. It favors a public-health response to drug addiction, with medical staff trained to observe drug use, counteract overdoses, and offer treatment. Its motives are admirable. But Congress has made it a crime to open a property to others to use drugs…. And that is what Safehouse will do.

Because Safehouse knows and intends that its visitors will come with a significant purpose of doing drugs, its safe injection site will break the law. Although Congress passed [a law] to shut down crack houses, its words reach well beyond them. Safehouse’s benevolent motive makes no difference. And even though this drug use will happen locally and Safehouse will welcome visitors for free, its safe-injection site falls within Congress’s power to ban interstate commerce in drugs.

Safehouse admirably seeks to save lives. And many Americans think that federal drug laws should move away from law enforcement toward harm reduction. But courts are not arbiters of policy. We must apply the laws as written. If the laws are unwise, Safehouse and its supporters can lobby Congress to carve out an exception. Because we cannot do that, we will reverse and remand.

Among those celebrating this decision was Jason Dunn, the U.S. Attorney for Colorado. “I commend and agree with the federal appellate court’s decision finding that facilities opened with the purpose of having visitors use heroin and fentanyl are doing so in violation of federal law,” he said in a statement on the ruling. “And as I have said previously, the idea of a government sponsored drug house is an anathema to the principle that government’s primary duty is to do no harm. We cannot combat the opioid epidemic by enabling individuals to access and use illegal deadly drugs, particularly in light of the recent rise in illicit fentanyl use. Such facilities would only serve to further the illicit drug trade and result in a greater number of overdose deaths, not less.”

Raville could not disagree more strongly. “Here we have Jason Dunn celebrating a ruling against a true lifesaver that would have helped everybody,” she says. Still, she’s hopeful that the inauguration of President Joe Biden will lead to a change of course on the federal level, possibly including the sort of legislation Bibas referenced in his opinion.

“We’re not deterred,” Raville stresses. “I know we can do better.”

Click to read the decision in the United States of America v. Safehouse.