Creative Commons / Flickr user sachab

Audio By Carbonatix

When Mayor Michael Hancock delivered his 2018 State of the City address on July 16, he repeatedly championed the $937.5 million in bond money that Denver voters approved last November, hailing ways the funds will be used to add parks, transportation infrastructure and jobs.

“Every single person in this city will benefit from these improvements. Every person. Our libraries are getting an upgrade. Our parks and museums are going to get better. Our streets are going to be safer, and we will have more connected bike and pedestrian networks,” the mayor declared. “Several neighbors are here representing the thousands of residents who helped shape the Elevate Denver bonds. Please stand. Let’s give them a hand!”

But in a counterpoint speech delivered on the same day, mayoral candidate Kayvan Khalatbari shared a vastly different outlook of the bonds, which he lambasted as a shortsighted investment. With $937.5 million being financed by big Wall Street banks, Khalatbari reasoned that day, the city will end up paying approximately $700 million in interest over a decade – money that will largely leave Colorado and line the pockets of East Coast bankers.

Kayvan Khalatbari

Khalatbari explains in a follow-up interview with Westword that the solution to paying all that interest is to set up a public bank that belongs exclusively to the City of Denver and keeps money within a closed loop.

“It’s a way to keep our money here as opposed to holding it in these large Wall Street banks that we pay egregious interest and financial fees to,” Khalatbari says. “This is not a new idea, these exist all over the world. Germany is fueled by public banks, and look, they have the best economy in Europe. North Dakota has a public bank, and they got through the recession better than any state in the United States.”

And dozens of counties, cities and states across the country – from New Mexico to California – are looking into opening public banks. They could even service the cannabis industry, which has trouble accessing financial services from large, national banks because marijuana remains illegal at the federal level; the State of Massachusetts and the City of Los Angeles are considering public banks specifically aimed to serve local marijuana businesses.

So what is a public bank, and how does it work?

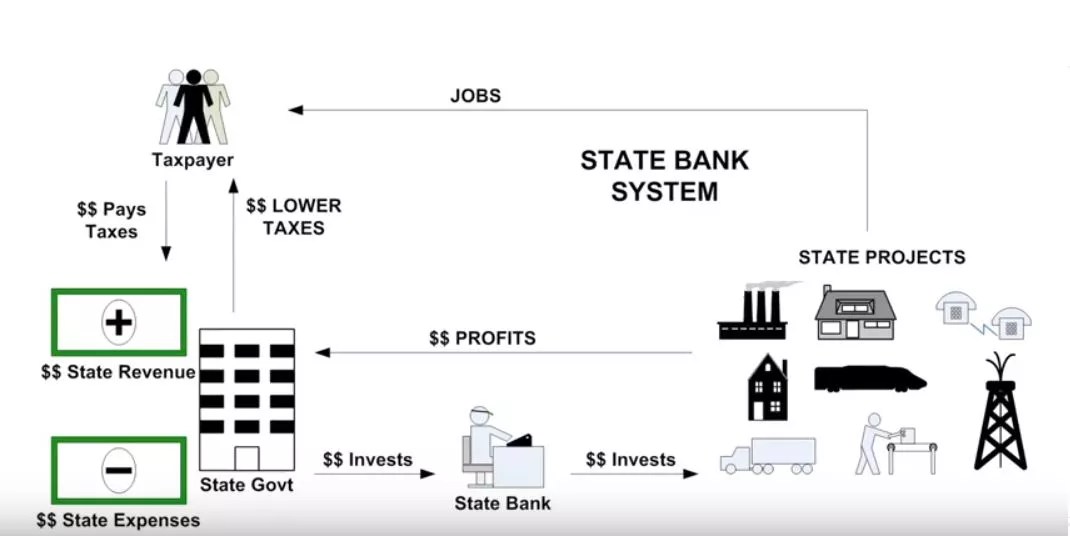

Put simply, a public bank is a government-owned and -operated repository for public funds. The bank collects taxpayer money and serves the interests of the state or municipality for which it’s chartered, and employs skilled bankers to manage funds and make loans. As a government-owned entity designed to serve the people, a public bank uses its resources to invest in the community and issue loans, usually with significantly lower interest rates than those offered by traditional banks.

This flowchart explains how a state owned public bank works.

Screenshot from YouTube video by InContext Report

American private banks accumulated power during the post-World War II economic upswing by offering more types of personal accounts to individual customers and by inking contracts with government entities. But in the past twenty years, which saw the dot-com bubble burst and the worst recession since the Great Depression, trust in private banks has eroded. Meanwhile, the Bank of North Dakota, established in 1919, has seen record returns (17 percent ROI in 2017) as it continued investing in the state while large East Coast banks pulled back on lending there.

Earl Staelin and Laura Richards of the Rocky Mountain Public Banking Institute have been advocating for a statewide public bank in Colorado for over two years.

“The major banks – Wells Fargo, Chase, Bank of America – they don’t like to lend to small businesses,” Staelin says. “The reason for that is because they’re not local, they don’t know the customers, and their goal is to maximize profit for their shareholders, and they think they can do that by investing in derivatives, credit fault swaps, and things that don’t do anything for the local economy, and in fact risk the national economy.”

Richards says that it’s this hesitancy among big private banks to lend to small businesses that drives her advocacy of a statewide public bank. She says that rural counties in Colorado that don’t get much investment would have an easier time getting loans – and at lower interest rates – through a public bank.

Richards also sees a public bank as a way to issue or refinance student loans at reduced interest rates – an option currently available through the Bank of North Dakota.

But there are roadblocks ahead. The City of Santa Fe recently decided not to establish a public bank, in part because it couldn’t support a minimum $100 million in capital to get it off the ground. There are also legal uncertainties, buttressed by the likely threat of litigation by private banks like Chase or Wells Fargo.

Staelin and Richards have been working with legislators in Colorado to introduce a bill next session that would allow for public banks in Colorado and counteract any potential litigation from private banks.

“The legislation, similar to what California is considering, will say that the State of Colorado recognizes and authorizes the issuance of charters for public banking at the state, city and county levels,” Richards says. (The state government issues bank charters in Colorado, so a public bank exclusive to any municipality would still need to be approved by the Colorado Division of Banking.)

Most arguments against public banks center around ethics and conflict-of-interest concerns – that contractors and companies with political inroads would be more likely to obtain loans and financing through a government-controlled public bank.

But even with these hurdles, Khalatbari is making public banks a central campaign issue heading into next May’s mayoral election. Given what he knows about public banks, he’s become more critical of Mayor Hancock’s celebration of the GO bonds.

“I would compare it to someone buying a million-dollar home when they make $50,000 a year and having that all be in debt, and then claiming it as a victory,” says Khalatbari. “It’s beating your chest for something you paid for though debt. It’s counterintuitive to the American Dream. To live off debt is not a way to live. That’s playing with people’s money in a way that’s irresponsible.”