Evan Semón

Audio By Carbonatix

A visit to Denver’s Riverside Cemetery sometimes feels more like trespassing than it does paying respects to those fallen folk heroes whose names now grace Colorado’s streets, towns, counties and mountains. It certainly doesn’t look like a place where life is celebrated.

Anthills rise up like tombstones above the graves of three recipients of the Medal of Honor – the military’s most prestigious award, and one that both President Teddy Roosevelt and World War II General George S. Patton lobbied for and never received.

BNSF railroad cars ten paces away rattle the final resting place of Silas Soule, the Union Army captain whose refusal to participate in the Sand Creek Massacre eventually brought a measure of accountability for the slaughter there, winning him a place in the history books…and likely his own assassination in April 1865.

Uneven clumps of buffalo grass snake their way around the graves of at least three Colorado governors and nine Denver mayors. That is, when there’s grass at all. During the dry months and throughout particularly dry years, Riverside is a pallid patch of brown punctuated by solemn gray monuments, some missing pieces and others moldered down to nubs.

No matter the season, off in the distance looms the smokestack of the Cherokee Generating Station as the stench rolls in from the largest wastewater treatment facility in the Rockies, just a block away, and tanker trucks lumber to and from Suncor’s refinery, right across the street. Good luck finding much in the way of tree cover to escape the glare of the sun. This is what the Rocky Mountain News once called “one of the loveliest cemeteries in the country”?

Compared to more easterly peers, Denver is a young city. Many of the sites where its short history happened met the wrecking ball early on and were turned into parking lots. Local cemeteries stand as some of the only places where you can come face to face with the names that made Denver Denver.

Denver’s last resting place

“People want a connection to history, but the only connection they have is a gravestone,” says Joe Jordan, who has volunteered at Riverside since 2012 and whose partner, Marcus Shirah, has been buried there since 2018. “That’s because the houses, the department stores, the mercantile stores are all now something else.”

What, then, is Riverside? A cemetery, certainly, but not an abandoned one. As Denver’s oldest operating cemetery, it remains one of Colorado’s most significant historic sites – anthills, tumbleweeds and all.

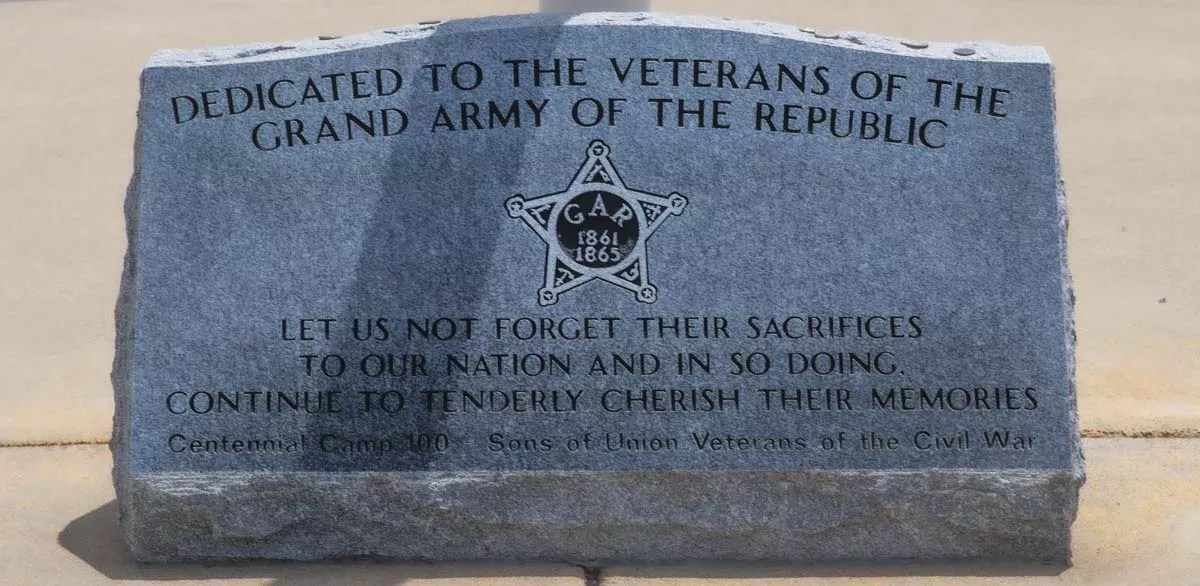

“It’s got the most Civil War veterans of any cemetery in Colorado,” about 1,200, according to local historian Ray Thal, who has volunteered at Riverside since 2004. Most of the cemetery’s Civil War plots were bought and owned by the Grand Army of the Republic, the fraternal organization for Union veterans that proclaimed and popularized what would become Memorial Day.

Many Civil War soldiers are buried at Riverside.

Evan Semón

Then there are the namesakes. Routt County is named for John Long Routt, who was Colorado’s last territorial governor and the first and seventh governor of the State of Colorado. He’s buried at Riverside, not far from the grave of Miguel Antonio Otero, a delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives for New Mexico and one of the founders of La Junta; Otero County is named for him. Mount Elbert, Colorado’s highest peak, and Elbert County are named for former Colorado governor Samuel Hitt Elbert, who’s buried at Riverside. Next to him, his father-in-law, John Evans – the second territorial governor – who founded Northwestern University and what became the University of Denver; he’s also the namesake of Evans, Colorado, and Evanston, Illinois. Evans used to have a mountain named for him, too, until he was found culpable of creating the conditions that made the horrors at Sand Creek possible; today that peak is Mount Blue Sky. Decidedly less controversial Riverside residents include John Silverthorn, a beloved judge from whom Silverthorne takes its name; Richard Sopris, an early Denver mayor who has a mountain honoring him in Pitkin County; and Hiram Bennet, the first territorial representative to Congress, who lent his name to Bennett, Colorado.

Don’t forget the firsts: Eliza Pickrell Routt, partner to Governor Routt, was a powerful suffragist leader in her own right – and the first woman registered to vote in Colorado. The grave of Alice Polk Hill, Colorado’s first poet laureate, is an amble away; she was the only woman involved in writing the City and County of Denver’s 1904 charter.

The founder of Colorado’s first school and first public library, Owen J. Goldrick, is at Riverside. So is Marshall Wilson E. “Bill” Sisty, purportedly Denver’s first law enforcement officer, as well as Sadie Likens, Denver’s first police matron and the second female jailer in American history. The place is positively brimming with members of the prestigious Colorado Society of Pioneers, folks who arrived in Colorado before February 1861 and were formally recognized for helping shape the place. The grave marker for Tadaatsu Matsudaira claims he was Colorado’s first Japanese resident, while Park Hee Byung’s monument recognizes him as the “founding father of Korean immigrants in Colorado.”

In the past, Riverside had a large staff. Today, it has two employees…and lots of volunteers.

Denver Public Library

Riverside was an early example of an integrated cemetery. “That’s probably the most important thing to say about Riverside Cemetery, that it had no segregation policies,” says Thal, the historian and tour guide. “We pretty much have every prominent person of color in early Denver history at Riverside.”

The cemetery’s burial cards constitute historically significant records of Colorado’s African American community, for which comparatively little information exists as a function of structural racism in recordkeeping. At Riverside, you can pay respects to Clara Brown, one of Colorado’s first Black settlers; born into slavery, she found freedom in the West, prospering in business while winning wide acclaim for her philanthropy. Or Barney Ford, who escaped slavery via the Underground Railroad and became one of early Denver’s most important business leaders. Both are honored with intricate stained-glass displays at the Colorado State Capitol. At Riverside, they’re joined by thousands of Black Coloradans – from Colorado’s first Black baseball player, Oliver Marcelle, to Civil War veterans to beloved friends and family members who shaped neighborhoods and communities the state over.

All told, somewhere around 67,000 people from all walks of life rest beneath Riverside’s 77 acres – though the exact number of burials is tough to pin down, since somewhere between a third and a half don’t have grave markers, according to Thal. He also suspects that many grieving families, especially those who lost children, would sneak out to Riverside and bury their loved ones under the cover of night.

Riverside keeps adding residents

Interments continue to this day, though they’re all well documented and aboveboard. And it’s largely the relatives of those recent residents who express frustration about the cemetery’s upkeep – or lack thereof. Sometimes they blame the owner, the Fairmount Cemetery Company, for favoring its other property, Fairmount Cemetery – billed as a “lush park” in marketing materials – while neglecting Riverside. Others fault the City of Denver, which they believe ought to do something more to maintain a place so important to its history.

The Fairmount Cemetery Company continues to invest in Riverside Cemetery, including adding this new marker at its entry.

Evan Semón

Universally, they wish it were more verdant.

“It’s just terrible to me, I’m going to be honest. It’s ugly, there’s no green,” says Tania Young, whose husband, Ian Young, was laid to rest in a plot at Riverside in 2023. In life, he chose the cemetery because of its historic Russian Orthodox burial ground.

“It’d be nice if it was a bit more welcoming, or more uplifting, or a place where you could feel more comforted. It’d be nice if they watered the trees to at least keep the trees green,” says James Monte Megas. He and his siblings buried their mother, Betty Collins, there in 2016 at a plot not far from her mother and father.

“It’s really depressing. Sometimes in the summer when you go, it’s just like brown dust and dirt,” says Christine Telea, whose twin sister, Liz, was interred there in 2021 near their parents.

The great irony at the core of Riverside’s history is that nearly identical pleas for greener pastures were the reason the place came to be. While Riverside is Denver’s oldest operating cemetery, it’s not Denver’s oldest cemetery. That distinction goes to what’s now known as Cheesman Park, which is still home to more bodies than you might expect as a function of the years it spent first as Mount Prospect Cemetery and later the Denver City Cemetery.

Opened in 1858, by 1874 Denver City Cemetery had become “a boneyard that is the most shunted and neglected suburb in the city – given over to owls and bats,” according to Riverside’s first prospectus. Tastes had changed as the intricacies of the Victorian era took hold; earlier cemeteries, such as the Denver City Cemetery, were designed to be sparse – so much so that it was nicknamed “Boot Hill.” It was a place to store remains, out of sight and out of mind – but it wasn’t somewhere that people were clamoring to visit.

In its early days, Riverside was a model for park-like cemeteries.

Denver Public Library

“That’s how Riverside started. They didn’t want their loved ones to be buried in this ugly-looking place anymore,” says Annett L. Student, the author of Denver’s Riverside Cemetery: Where History Lies, an exhaustively researched book on Riverside’s history.

Incorporated on April 1, 1876 – months before Colorado became a state – it was modeled after the leafy Mount Auburn Cemetery near Boston, the nation’s first garden cemetery, according to Riverside’s successful 1994 application to the National Register of Historic Places. Riverside became Colorado’s first park-like burying ground, a pioneer of the format that comes to mind whenever anybody says “cemetery” to this day. Gravesites, as described in the National Register of Historic Places listing, were “laid out in well-kept lawns surrounded by flowers, trees, and winding drives.”

Riverside accepted its first burial on June 1, 1876: Henry Walton, whose white marble obelisk still stands, though it disintegrates a little more with each passing year. By that July, Dr. John H. Morrison had joined Walton as the fifth burial, a loss – or perhaps an addition – made poignant by the fact that Morrison was the original owner of the land beneath what would become the cemetery.

So successful were Riverside’s initial marketing efforts that families began transferring their loved ones there from the Denver City Cemetery. The Grand Army of the Republic started moving Civil War veterans into its plot at Riverside from various burial places in 1886; Silas Soule’s remains made the trip from City Cemetery at some point not long after, though the thirteen-foot monument over his original grave didn’t go with him, replaced instead by a spartan veteran’s headstone in the traditional style.

By August 1885, the landscaping had blossomed to the point that the Rocky Mountain News called Riverside Cemetery “one of the most attractive points in the vicinity of the metropolis.” Its lawns were described as “velvet-like…perhaps the finest in the natural world,” with “many thousand trees now growing.” Jerome Smiley noted in his 1910 History of Denver that Riverside was a “most beautiful city of the dead, adorned with shrubbery and lawns and costly monuments.” A 1923 promotional pamphlet for the place bragged about its newly rebuilt irrigation system and pumping plant. “More burials are made at Riverside than at any other cemetery in or near Denver because of its accessibility, convenience, and attractiveness,” it claimed.

So how did Riverside go from a sumptuous park celebrating life to a barren field reminding visitors that death comes for us all?

The place looks like death

It’s tempting to think of a cemetery as a place suspended in time, since its residents tend to be, and because the families footing the bill expect a final resting place to be final. But nowhere can ward off change completely, even if a cemetery can reasonably stave off new development within its hallowed borders – barring a literal Act of Congress, as in the case of Cheesman Park.

First, the Burlington and Colorado Railroad came for Riverside, cutting a line across its southeast corner in 1881. Then came industry, drawn to the rail connection and the Platte River access that gave the cemetery its name: slaughterhouses, junkyards, smelters and the other industrial operations common to a city’s outskirts. These were not the tony residential developments Riverside’s founders anticipated – especially compared to the digs surrounding Fairmount Cemetery, which was organized in 1890 to give Denver residents a more upscale place to spend eternity.

The railroad cuts by the graves.

Evan Semón

“That spelled the demise for Riverside,” according to historian Student. “If the rich and wealthy didn’t want to be buried there, that took the money away. You know, that’s life. Life happened, and it didn’t happen well for Riverside.”

The central paradox of a cemetery is that it commemorates the inevitability of the end while also requiring continuous growth. When the burials stop, the money stops – save for interest earned from perpetual-care endowments, which at Riverside doesn’t amount to much. “What a cemetery is selling are burial services and real estate,” says Chris Keller, the treasurer of the International Cemetery, Cremation and Funeral Association and a Colorado-based cemetery consultant. Just as few people clamor to live next to a meatpacking plant, few people want to be dead next to one.

By January 1900, Fairmount, very much the bourgeois cemetery on the rise, had acquired Riverside. The latter became the lesser, relegated to something of a potter’s field, with “welfare cases” rising to about 25 percent of the cemetery’s interments, according to Student.

Critics claim that Riverside’s story since its acquisition is a “tale of two cemeteries,” and that the Fairmount Cemetery Company’s minders realized that Riverside was a poor investment and directed their time, money and care to the more profitable of the two burial grounds, leaving Riverside to wither. It is undeniable that since the 1920s, Fairmount has had more money coming in – and that money chases money.

But Fairmount management hasn’t necessarily walked away from Riverside. In fact, according to cemetery expert Keller, the company has “spent a fair amount of its operational income to maintain and improve” the place. Without Fairmount’s ownership and its namesake cemetery’s comparative success and resources, there’s a good chance Riverside would probably be a lot worse off.

As for the parched environs, it isn’t entirely that Fairmount was tired of footing the watering bill for paupers’ graves. Newspaper articles from as recently as 1970 call Riverside “a green oasis in an industrial desert” and feature Fairmount Cemetery Company executives launching a $250,000 improvement campaign while pledging to continue to plant grass and water flowers.

History had other plans, though. A series of 1981 court judgments proclaimed that Riverside didn’t possess the water rights to the South Platte River that it had relied on since 1879. From 1981 on, Riverside negotiated a flat, discounted rate from Denver Water; that agreement, purportedly memorialized by only a handshake, fell apart under scrutiny in 2001 – and the cemetery couldn’t afford the new, contractual going rate. Watering operations ceased altogether in 2003, a particularly ironic development for the cemetery whose most impressive monument might just be the one honoring the founder of what would become Denver Water, James Archer (though he’s buried in green acres somewhere else).

Much of Riverside’s tree canopy died off during a blight in the 1970s, and most of the rest disappeared with the turf when the taps turned off. “In the prairie, which is where Riverside is located, you can’t keep seventy acres of lush turf and non-native, water-hog trees growing without water,” Keller notes.

Is Riverside dying a prolonged death by dehydration? Its appearance in 2024 is hardly comparable to that of Denver City Cemetery, whose indisputable “death” 140 years prior gave rise to Riverside. Sure, some of Riverside’s monuments are shopworn, but they aren’t crumbled across the ground in chunks. Sure, very little looks manicured, and an especially angry mother goose might hiss visitors away from its nest in a thicket between gravestones, but there are clear, clean roads and paths from which you can safely explore history. Sure, trains blast by and sewage stench wafts in on the back of dust storms, but there’s no trash blowing about – and many gravesites, especially Soule’s, still feature flowers left with love. In the spring, serene patches of wildflowers leap forth, often rising much taller than the anthills.

A statue guards the graves of Union soldiers in the section devoted to the Grand Army of the Republic.

Evan Semón

Robin Brilz, the director of the Fairmount Heritage Foundation – which works to “protect the heritage of Riverside and Fairmount for future generations” by organizing volunteer opportunities, educational tours and genealogical research – points to the fact that Riverside employs two full-time employees who work on upkeep, plus contractors in the summer. Name another “abandoned” cemetery that makes payroll.

Or consider the loyal company of active volunteers, around 45 in all, according to Brilz. Thal and Jordan are part of that crew, and they each fell so in love with Riverside that they purchased plots for themselves and their loved ones there. “A lot of people think that nobody in Denver cares about Riverside because they’re expecting grass,” Jordan says. “If we were letting it go to hell, we wouldn’t volunteer our time out there. The other day we had over sixty people from an outside volunteer group come to help clean up the place. If nobody cared, we wouldn’t have that.”

Riverside’s boosters, like Brilz, Jordan and Thal, are quick to point out that Riverside will likely never be in the financial position to pipe water back in, though they contend that’s probably a good thing. “If you have water continually spraying some of those stones out there, they would be lost because they would just melt,” Brilz says. “I’d rather keep that history than have a big, green, lush, park-like cemetery.”

That history, after all, is the main point. Riverside’s importance flows not just from the legacies, good and bad, of some of the folks buried there – but by dint of existing as a cemetery at all as burial itself goes out of vogue. Coloradans increasingly prefer cremation – which, Keller estimates, accounts for 65 to 75 percent of the disposition of Denver-area remains. Ashes end up scattered to the wind or tightly packed in columbaria, though some are buried. What’s more, by his math, it takes a new cemetery around 22 to 24 years to just break even, and it’s a lot more profitable to use that land to build housing, strip malls or, yes, sewage treatment plants.

Concerns about cremation’s carbon emissions give rise to various natural burial movements, whereby the dearly departed are interred without caskets, concrete vaults or the embalming fluid that became trendy when Abraham Lincoln’s corpse was pumped full of it so that the slain president would look lively to mourners. That could lead to a return to burial grounds, and a special interest in making the most of extant ones such as Riverside.

Volunteers have been beautifying Riverside Cemetery for Memorial Day.

Evan Semón

And so, for as much as it may sometimes look like a disregarded artifact of history, Riverside’s past has a lot to say for the future of the western cemetery.

An afterlife for Riverside Cemetery

Frank Rossi is a professor in the horticulture section at Cornell University’s School of Integrative Plant Science, and an international expert in the science of grass and turf. He was part of the team that converted portions of Brooklyn’s famously manicured Green-Wood Cemetery from ornamental lawns to natural, overgrown meadows and grasslands. For him, the math is simple: As water became scarce for Riverside, it might become scarce for the rest of the American West.

“Is a green-grass Victorian cemetery an anachronism in a world starved for water? The answer is yes,” he says. “Whether it’s cemeteries or other what are primarily aesthetic grasslands, like lawns, I think everybody is going to be questioning the value of it.” In that way, Riverside perhaps has a leg up on Fairmount Cemetery and all the memorial parks that it came to inspire in Colorado: Every green cemetery will likely die, at least in part, and Riverside got the dying part out of the way a long time ago – including all the denial and anger that make up key stages of grief.

For Riverside to stand as a model for future cemeteries depends mostly on factors beyond the cemetery’s gates. Keller suggests there’s a chance that the surrounding neighborhoods morph from warehouses, recycling centers and trucking depots to a trendy blend of housing, entertainment and dining – an idea not out of the question, given the significant redevelopment nearby of both the National Western Center and what is now the RiNo neighborhood, for better or worse.

In that scenario, Riverside’s historical pedigree, along with the twin logistical and ethical nightmares of moving at least 67,000 bodies, probably protect it from becoming condos. Its new neighbors, though, would insist on some form of investment in the thing just to prop up property values: Imagine a lightly irrigated Riverside dotted with low-water native trees and plants that look best when overgrown.

An afterlife as the Botanic Gardens of Brighton Boulevard is an uplifting thought – but like all plans for the afterlife, it’s ultimately just speculation.

What is undeniable is that this cemetery started out as prairie land, unkempt and unbowed. It indelibly shaped its surroundings, inspired Denver residents and influenced history in a way that at least history-minded people care about. With age, it broke down and decomposed to the extent that many folks simply prefer to remember how it used to be. It is now prairie land once more.

In that way, Riverside Cemetery isn’t a place to engage with history or even store remains. It’s a model for confronting mortality; insisting on a green cemetery is a form of denying death. Places like Riverside remind the living that “all are of the dust, and all turn to dust again” – no matter who you are, or what your name might be.