Pete Ryan

Audio By Carbonatix

More than a month after her daughter’s murder, Connie Jones still drives by the spot where she was killed, a patch of brush tucked behind a warehouse near the South Broadway and I-25 interchange. It’s not an area that Jones had frequented before, not even for public transportation at the sprawling RTD train and bus hub underneath the freeway overpass. But in recent weeks, Jones has been coming here from her home in Sheridan almost subconsciously, in a sort of ritualistic search for answers – or any kind of solace after losing her second child.

So far, those answers have been painfully elusive; during moments when Jones snaps out of her trance, realizing that she’s once again driving by the spot, she finds it hard to imagine how things had gotten to the point that her 28-year-old daughter, Nicole Boston, was sleeping on hard dirt, outside and exposed. She finds it hard to imagine what the final moments were like between Nicole; her 39-year-old husband, Jerome Coronado; and a third man, 45-year-old Christopher Zamudio, as they camped together, hidden from public view. And she finds it impossible to imagine what drove someone to gun down the three sometime between the evening of Wednesday, August 8, and 11 a.m. Thursday, August 9, when their bodies were discovered.

After the Denver Police Department reported that three bodies had been spotted behind a building at 765 South Broadway, television stations streamed footage from choppers whirling over the crime scene. “If it bleeds, it leads,” goes the sardonic saying in the news business. And sure enough, every station made the murders a top story: It was the first triple homicide in Denver since a drug deal gone bad in Park Hill during the summer of 2016.

The initial reports had little information about the victims, not even their names or how they had died; that wasn’t released until the Office of the Medical Examiner put out a bulletin the following Monday, August 13. Given the dearth of details, news outlets seized on the one fact that police provided: The victims were all homeless.

“Oh! That was your daughter? Why was she homeless?”

Of everything Jones has experienced since losing her daughter, what has been perhaps the most difficult is the focus on homelessness. The grieving mother has been shocked by how quickly people have jumped to judgments or assumptions. When the murder came up during a recent conversation with a woman at a gas station, the stranger blurted, “Oh! That was your daughter? Why was she homeless?”

Another thing that blindsided Jones was how soon the public seemed to forget this triple homicide and move on to other stories, other scandals, other tragedies that bleed and lead. But Jones keeps driving past the warehouse on South Broadway. For her, the story can’t be over; she’s had to continue dealing with the fallout – awaiting updates from police detectives investigating the shooting, arranging a reading of Nicole’s last will and testament.

And taking care of Nicole’s three children, all under the age of thirteen, left parentless by the murders.

On social media and in private conversations, Jones has shared the real story with anyone who will listen: Yes, Nicole Boston, Jerome Coronado and Christopher Zamudio were all people who happened to be experiencing homelessness, but they were first and foremost people. They were people with histories, individual triumphs, failures, hopes and dreams.

Jones acknowledges that her daughter was living on the streets on the night she was killed, but that wasn’t because of family neglect or any lack of trying to find help. “I don’t think that was supposed to be the end of her story,” Jones says. “Especially after all the pain we already went through together.”

Connie Jones is still reeling after the death of her daughter, Nicole Boston, in a triple homicide last month.

Kenzie Bruce

Nicole Boston didn’t make it to her thirtieth birthday, but her mother had always viewed her as going on thirty. “We used to say she was an old soul,” Jones remembers.

From a young age, Nicole was headstrong and sassy, yet she would always take responsibility for her actions. Over and over again, she rose to the occasion when the going got tough. Her first real challenge came when she was sixteen years old, a student at Sheridan High School, and got pregnant. She and her boyfriend, Daniel Terrones, whom she’d been dating since the eighth grade, decided to have the baby.

“Everyone said she was going to drop out of school or go on welfare,” recalls Jones, who’d had Nicole when she was a teenager herself and raised her as a single parent most of the time. “Well, my daughter ended up being the valedictorian of her class – and with a two-year-old baby!”

Nicole and Terrones were planning to get married shortly after her graduation. But early on the morning of April 13, 2008, Daniel Terrones, who was just shy of his 21st birthday, was standing in the living room of his sister’s home in west Denver when two bullets pierced a wall, striking him in the chest. His death sent Nicole reeling. Suddenly Terrones was gone, and their toddler, Mia, was fatherless.

Nicole still managed to give the valedictorian speech at graduation a few weeks later. Without explicitly mentioning Terrones’s death, she talked about persevering through unforeseen challenges – as her fellow students knew she was.

The police never solved Daniel Terrones’s murder, and the circumstances around his death remain a mystery to his family, according to his brother Jason. Daniel wasn’t in a gang, Jason says, and with no leads, the case went cold. Denver Police Department detectives stopped calling Nicole and members of the Terrones family after about a year, Jason adds: There was just nothing left to say, since there were no suspects or other updates on the investigation.

For years afterward, Nicole kept Daniel’s memory alive, hounding television and radio stations to allow her to do on-air interviews on the anniversary of his death, during which she advocated on behalf of victims in cold cases and pushed for an end to gun violence.

Practicing what she preached in her graduation speech, Nicole did persevere. She attended Arapahoe Community College, then landed a sales job at DISH, rising through the ranks of the communications company until she was appointed a team leader in charge of overseeing a dozen people. The team won the company’s top sales award for months in a row, Jones recalls.

Four years after Daniel’s death, Nicole began seeing another man, Jerome Coronado, whom she met at a clothing store. Eleven years Nicole’s senior, Coronado was affectionate with her daughter, and he and Nicole decided to get married. It was a happy time, Jones says. The couple soon had two children of their own, Kristian and Isabella, while Nicole continued to advance at DISH.

Nicole Boston, a mother of three, raised her kids in the suburbs of Denver.

Kenzie Bruce

But when Nicole was 25, another blow: She was diagnosed with a rare ovarian cancer, and doctors concluded that she would need to have a partial hysterectomy. After the surgery, Nicole started having seizures. Jones witnessed one: Her daughter mentioned having a strange taste in her mouth, then turned to Jones and said, “Oh, Mom, here I go.” Nicole collapsed to the ground in violent spasms as her mother looked on, helpless.

Despite innumerable tests, doctors couldn’t figure out what was causing the seizures, and Nicole became paranoid about when and where the next one would strike. After she hit her head during one particularly bad episode and was knocked unconscious, her doctors were obligated to tell the Department of Motor Vehicles, and Nicole lost her driver’s license.

“Before that, she had all these accomplishments she was so proud of,” remembers Jones. “Then she started slipping, slipping, slipping.”

And what made Nicole slip more than anything else was a growing addiction to pain medications. According to Jones, after Nicole’s surgery, her doctors had prescribed Percocet, then Oxycontin.

Nicole soon became hooked on opioids, as did Coronado. As their cravings surpassed Nicole’s supply, both turned to obtaining opioids on the street, including heroin.

“I felt like if she could just get sober, she could make decisions for herself again.”

The opioid crisis has grown far past the days when it affected isolated pockets in Appalachia into a national epidemic. In 2017, Colorado’s Department of Health and Environment reported a record 357 opioid-related deaths in the state. Local and state governments across the nation have begun fighting back. In Colorado, Denver has joined a team of twelve other municipalities suing pharmaceutical companies that make and distribute opioids, hoping that the companies will be forced to change their marketing practices and share some of the cost burdens of the health crisis. Last week, Attorney General Cynthia Coffman announced that Colorado has joined the states suing Purdue Pharma for “fraudulent and deceptive marketing of prescription opioids.”

As Nicole and her husband sunk further into addiction, the family tried to help. After Nicole lost her job at DISH, Jones tried taking her daughter to Arapahoe House, a now-defunct substance abuse treatment center. Because the center was not equipped to deal with Nicole’s seizures, officials there said she’d first need to check into a hospital to detox. Instead, Nicole and her husband stole things from her grandmother’s house and pawned them to finance their next fix. Jones had finally had enough, and filed restraining orders against the couple in mid-2016.

“My hope was that we would be able to get Nicole in jail and get her sober,” Jones remembers tearfully. “I felt like if she could just get sober, she could make decisions for herself again.”

It was devastating for Jones to watch how opioid addiction had consumed the couple, to the point that neither could care for their three children, who had moved in with their great-grandmother, Jones’s mother. Nicole and Coronado were erratic, fighting, breaking up and getting back together. They became difficult to trace, sometimes living at residential hotels, other times sleeping on the streets.

“I would go a month at a time without talking to Nicole,” Jones remembers. “Every night I would worry: Is she safe?”

Through it all, Jones believed that Nicole truly wanted to get sober and return to her kids; she just didn’t have the strength yet. So every time her daughter reached out, Jones continued to extend a helping hand. On August 7, she got another chance. That day, Nicole sent missives on Facebook Messenger to her mother and Mia, whose twelfth birthday was coming up that weekend. Nicole said she wanted to see them both.

Maybe this time she could help her daughter get clean, Jones remembers thinking. Maybe this time it would be different.

Three bodies were found behind this warehouse on August 9.

Chris Walker

On August 9, the Denver Police Department held a press conference near the crime scene where the bodies of Nicole Boston, Jerome Coronado and Christopher Zamudio had been found. Detectives and forensics experts were within view, collecting evidence behind a border of yellow police tape. Denver’s new police chief, Paul Pazen, was on hand to answer reporter’s questions, in one of his most notable public appearances since becoming Denver’s top cop on July 9.

During the press conference, questions increasingly focused on the victims’ homeless status. Pazen assured reporters that crimes committed against the homeless have the same priority as crimes against any other person in Denver. “Our message is that our team takes these serious, and we want to make sure that all people in Denver, [including] our most vulnerable community members, are treated with respect and dignity, and that the investigation is just as thorough for them as it would be for anybody else in this city,” the chief said.

Still, even with the case a top priority, police would have their work cut out for them. Identifying suspects who have committed crimes against homeless victims can be extremely challenging, even when the circumstances are shocking and sensational and rewards are offered.

On November 17, 1999, two headless bodies were discovered in a field behind Union Station (back when lower downtown had fields). After the decapitated victims were identified as “transients,” the city’s homeless community panicked. In the previous six weeks, five other homeless people had been murdered in Denver. As Rocky Mountain News reporters Hector Gutierrez and Lynn Bartels wrote at the time, “The gruesome discoveries in a field behind Union Station brings to seven the number of homeless men who have died brutal deaths in lower downtown since Sept. 7. Three were decapitated. Only one of the heads has been found.”

City officials, including Mayor Wellington Webb, were dismayed by the discoveries because the DPD had just arrested three youths, so called “mall rats” who spent time along the 16th Street Mall, in connection with one of the earlier murders; the three would later be convicted for stomping a victim, Melvin Washington, to death after Washington allegedly entered their “turf” on the mall to ask passersby for spare change.

“I thought the crimes had been solved,” Mayor Webb told reporters. “With the two additional bodies that popped up today, this obviously means we need additional resources to safeguard the people of the city.”

Although the DPD has never officially said that a serial killer was on the prowl, members of Denver’s homeless community had their suspicions, particularly because of the beheadings. More than 100 DPD officers were assigned to comb the field behind Union Station for evidence. Webb even tapped U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno for FBI assistance.

But six of the seven murders remain unsolved.

John Parvensky has headed the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless for more than two decades.

Anthony Camera

John Parvensky, who was then and is still the executive director of the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, remembers the 1999 murders well. As the bodies stacked up, his organization established a round-the-clock emergency tent in the Platte Valley, where the King Soopers at 20th Street and Chestnut Place stands today. “The community was pretty responsive to our requests for support,” Parvensky recalls. “We had food, water, a fire. We were providing a safe place to be.”

While the crimes in 1999 seemed particularly sensational, Parvenksy points out that people experiencing homelessness are always vulnerable. He says he’s been dismayed not just by the lack of progress in protecting the homeless, but by the public’s response to last month’s triple homicide.

“Certainly, while the community was shocked when seven people were murdered in 1999, today the murder of these three doesn’t seem to raise much of a stir,” Parvensky notes. “My sense is that we as a society have become desensitized to violence against homeless persons, just like we’ve become desensitized to homelessness itself. Twenty years ago, people would have been shocked to see the number of encampments and people sleeping on the streets like we see today. Now it’s more of an inconvenience than an unacceptable condition. People are able to think, ‘Well, they’re not really people like me. I don’t have to worry about that.'”

In 2011, the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless helped craft legislation that would increase penalties for bias-motivated crimes against people experiencing homelessness in Colorado. The “Crimes Against Homeless” legislation, as it was called when it was introduced by Senator Lucia Guzman and Representative Dan Pabon, would have added homeless adults and juveniles to the “Wrongs Against At-Risk Populations” statute under Colorado law.

The effort was part of a national movement to protect the homeless using hate-crime legislation; Florida had become the first state to pass such a law in 2010. That same year, the National Coalition for the Homeless had released a landmark report showing how, from 1999 through 2009 in 47 states, Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C., 1,074 acts of violence had been committed by housed individuals against homeless victims, resulting in 291 deaths of homeless people and 7,893 victims of non-lethal violence. The report listed Colorado seventh for the number of hate crimes carried out by housed individuals against the homeless.

Some of those crimes involved gangs and organized-crime syndicates. “We saw this disturbing pattern where gangs seemed to be carrying out initiation rituals,” Parvensky recalls. “Other times, it was just youth that had never met a homeless person and somehow thought it would a thrill to take action against someone who was invisible to them.”

But despite the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless’s efforts, the proposed legislation was killed at the State Capitol. “There was pushback from some communities, saying that the homeless shouldn’t be protected by hate-crime laws like other groups – that one’s race or religious or LGBT status was not the same as one’s housing condition,” Parvensky says. “Now people who are accessing shelters are more scared than they’ve ever been. Today, they don’t feel safe on the streets, mostly because there are more people in Denver – more people out there that may want to do them harm.”

Parvensky also sees a striking difference in the amount of attention from news outlets that the homeless homicides received in 1999 and the coverage of this year’s triple homicide. He acknowledges that the news cycle moves faster than it used to; there are also far fewer reporters in town. Still, mentions of the murders of Nicole Boston, Jerome Coronado and Christopher Zamudio quickly disappeared when news broke five days later that Shanann Watts, a pregnant woman from Frederick, and her two young daughters had disappeared. Her husband, Christopher Watts, was soon charged of killing all three.

“My communications director sent me a side-by-side comparison of articles about the three homeless victims on South Broadway – which had relatively few Facebook shares – and the tragic story of the [Watts family], in which one Fox News story had 11,000 shares in thirteen hours,” Parvensky says. “So certainly, the difference between a pregnant mom and kids versus the homeless on the streets shows that one is much more sympathetic to the public and moves people, while the other is [a story] most can’t relate to or understand.”

“Now people who are accessing shelters are more scared than they’ve ever been.”

Elisabeth Francis, an outreach worker for the St. Francis Center, makes the same comparison. But then, she knows the human side of this story: She’d encountered all three victims during the month before their deaths.

Unlike Nicole and her husband, Zamudio had been homeless for some time. “He was really kind,” Francis recalls. “When I talked to him the week before he was killed, he seemed kind of lonely and just wanting connection.”

Zamudio sometimes went by the street nickname “Little Cowboy,” and was known to lend a helping hand to others living on the streets when they needed it. When Francis saw him at a large encampment that had formed at Sixth Avenue and Broadway, he was watching someone’s dog while they were away from the camp.

People on the streets sometimes share their life stories with Francis, she says, but Zamudio tended to be quiet and reserved. “My last conversation with him, we were talking about how to get a replacement Colorado ID card,” she recalls. “That’s a common problem – IDs getting lost.”

It’s unclear how Zamudio knew Nicole and her husband, but Zamudio would have had to find a new place to stay after the city swept the encampment at Sixth and Broadway in early August. Homeless advocacy groups, including Denver Homeless Out Loud, denounce sweep operations, as well as the city’s urban-camping ban, for forcing people to move to unsafe and hidden locations. But Francis notes that Nicole, Coronado and Zamudio were all together when they were shot.

“As outreach workers, we tell people that, if you’re going to be camping outside, make sure you’re in groups for safety,” she says. “But it was a group that was attacked. So how do you plan for that? How do you protect yourself?”

On August 10, the day after the murders were reported, the St. Francis Center set up a resource table in Civic Center Park. “Honestly, no one wanted to talk about [the murders] that Friday,” Francis recalls. “We’re trying to let people know so they can make better safety plans, but for the most part, I’ve been shocked at how there doesn’t seem to be a strong reaction even in the community. I was mentioning that to a colleague, and she said, ‘I hope that doesn’t mean everyone has become numb to that kind of thing.’

“That’s hard to process for someone on the outside of the community looking in,” she adds. “But I wonder if folks can’t afford to think about it because it might be too debilitating to get through the day.”

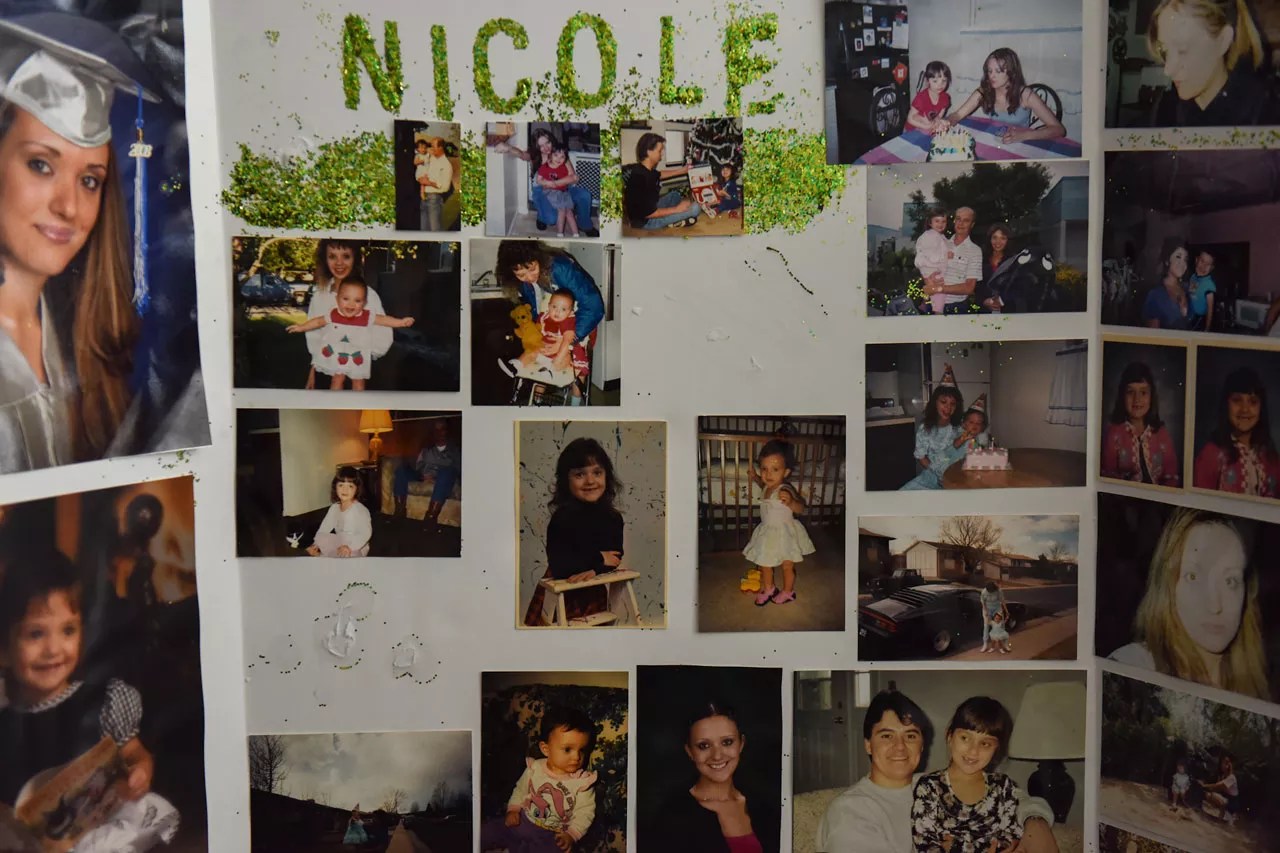

A poster that twelve-year-old Mia keeps in her room honoring her mom.

Kenzie Bruce

Getting through the day remains a challenge for those who were close to the victims of the August homicide. Family members and friends have taken turns caring for Nicole’s children: Mia, now twelve, six-year-old Kristian and three-year-old Isabella.

The two younger children are confused about what has happened. “One minute they recognize that their parents are gone, and the next minute they’re calling for them,” says Dominique Martinez, a close family friend who has started a GoFundMe page to support the kids.

One day when Martinez was babysitting the children, Isabella surprised her by saying, “I hate heaven.”

“Aw, why do you hate heaven?” Martinez replied.

“Because it has my mommy and daddy.”

“No, baby, it’s okay,” Martinez said. “They’re safe, and heaven’s not a bad place; they’re watching over you.”

Mia, the oldest, has stayed largely silent. One wall of her bedroom was already dedicated as a memorial to her biological father, Daniel Terrones. Now another wall is reserved for pictures of her mother.

Jones continues to experience moments of uplifting beauty and crushing despair. It was despair when she went to the morgue to identify her daughter, who was wrapped head to toe in thick insulation, save for a cutout for her face. Jones suddenly felt an unstoppable urge to hug her daughter one last time, but when she pressed herself against the wrapping surrounding the body, she had to squeeze harder and harder until she finally felt something solid. As a result of her addiction, Nicole had shrunk to 107 pounds.

“The candles, the community, the mourning. They really cared about my daughter.”

But in contrast, Jones was struck by the thoughtfulness of police officers leaving candles and flowers at the crime scene as a tribute to the victims. One officer said he’d met Nicole, and called her “a good kid.” Members of the homeless community left more candles at the spot, where Jones met a man who regularly sleeps nearby and told her that Nicole always kept her campsite clean and tidy. “A woman’s touch,” he said.

“The candles, the community, the mourning. They really cared about my daughter,” Jones says. “I mean, who doesn’t want a neighbor like that?”

Meeting people who’d known her daughter kept Jones grounded as she waited for news, any news, on the police investigation. Then on September 6, she got the call she’d been waiting for: The DPD had identified a suspect. A police detective told Jones, “I want you to know, you have a lot of people to be thankful for. People on the streets led us to the suspect. They wouldn’t hide him. They were key.”

Within hours of Jones’s conversation with detectives, the DPD sent out a bulletin identifying 38-year-old Maurice Butler as the suspect behind all three shooting deaths.

Butler had actually been in police custody since August 13, when he was detained on suspicion of parole violation and possessing a controlled substance. The DPD has reason to believe that Butler was familiar with two of the three victims, according to spokesman Sonny Jackson. “This was not a random incident,” he says, declining to elaborate.

Suspect Maurice Butler.

DPD

Jones doesn’t know much about Butler, but a detective told her that he had confronted Nicole, Coronado and Zamudio in order to collect a debt.

“I would have paid him ten times what he wanted,” Jones says tearfully. “My daughter is priceless.”

Having the police identify a suspect has been bittersweet: “I’m happy for all the people on the street who are safer now,” she says. Jones is also impressed with the work of the police. But knowing the name and seeing the mug shot of the man accused of killing her daughter hasn’t brought much closure.

“I’m not reacting the way I thought I was going to – having this big release,” she says, faltering for words.

“When you lose your child, it just feels like a part of you is gone. And I don’t know if that will ever go away.”

On August 17, Jones organized a vigil at the crime scene to honor all three victims. During the remembrance, a few dozen people – mostly family and friends of Nicole’s – released a batch of balloons, which peacefully rose into the sky above the noise and gridlock of I-25.

Jones delivered the main eulogy, during which she noted that everyone was standing only a couple hundred feet from where she had been parked the night before the three bodies were found. She’d been waiting for her daughter.

When Nicole had reached out to Mia and her mother about coming home that weekend, Jones had arranged to meet her daughter at the RTD station on Wednesday evening, August 8. Her last words to her daughter on Facebook Messenger: “Come home. I’ll be there. I’ll be waiting for you.”

Update: Tuesday, September 11: Denver District Attorney Beth McCann has formally charged Maurice Butler, the DPD’s suspect in the triple homicide, with three counts of first-degree murder. “The quality investigative work of the Denver Police Department was relentless and exceptional in this case,” she said in announcing the charges. Butler’s first court appearance is scheduled for September 14.