Getty Images/Westword photo illustration

Audio By Carbonatix

East High School seniors say they’re to blame for the Target on South Colorado Boulevard running out of swim goggles and pool floaties in the middle of winter: Those items are their only protection during the school’s almost-annual game of Assassin, resurrected in 2022 after COVID caused a two-year hiatus.

In Assassin, pairs of seniors are assigned to target other pairs of seniors, trying to douse them with squirt guns. If the students are wearing swim goggles or have floaties around their arms when they’re hit, they’re protected. Otherwise, they’re eliminated.

Legend has it that Regis Jesuit High School was the first in Denver to play the game, a variation on a pastime at high schools across the country, and it spread from there to other schools in the area. At East, where it’s been played since at least the early 2000s, Assassin has been elevated to an art.

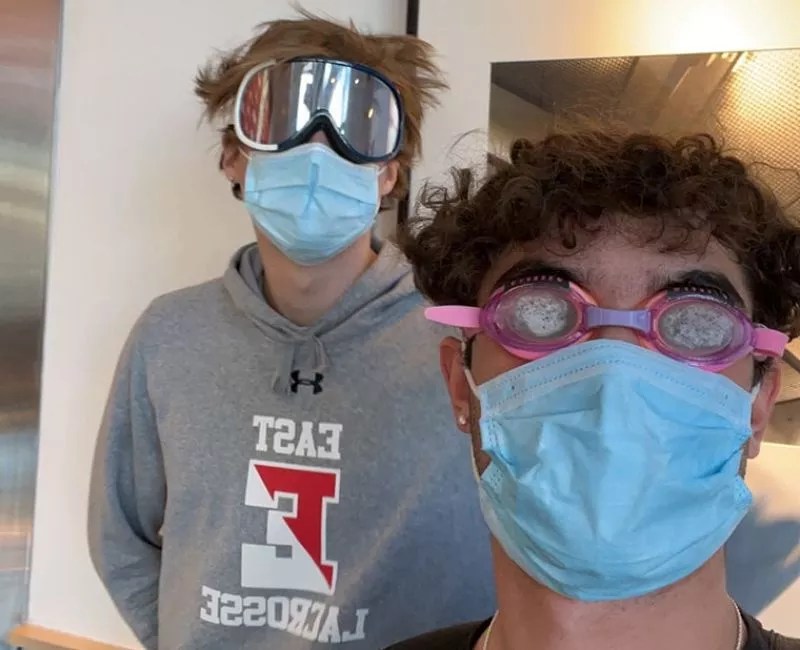

East senior Annabel Filippini organized this year’s game because she realized that if no one took the initiative, the Class of 2022 would lose out on yet another tradition after weathering periods of remote learning and seeing myriad events canceled.

Annabel Filippini (right) organized this year’s game of Assassin with help from friend Ellison Mucharsky.

Catie Cheshire

“I was like, ‘Annabel, you just need to get on this, because we can’t wait for anybody else to do it,'” says friend and fellow Assassin Ellison Mucharsky. “We’ve all been suffering because of COVID for so long, and I think this would just be a great way to kind of go out and boost the morale of the senior class and be able to bring everybody a little bit more together again.”

At the start of the new year, Filippini set up an Instagram account, @east2022seniorassassin, and began spreading the word that Assassin was back at East High. Social media is used for everything at the school, she says, and this was a way to ensure that it wasn’t just her friends who heard about the game. As a result, 244 East seniors, or about 20 percent of the graduating class, kicked off play on January 24.

Assassin is broken up into three sets that are each four weeks long, so the game will last until at least April 15 – and maybe longer, if Filippini decides that spring break is an off week or if a large number of teams are left after twelve weeks, making it difficult to narrow the field to a winner. During the first two sets, if someone’s partner is squirted, the surviving partner is placed on a bounty list – eligible to be eliminated by anyone, not just the team assigned to target the pair. In the first set, people on the bounty list can wear protection; in the second, they can’t. In the last set, if someone’s partner is eliminated, that person is, too. At any time in the game, when a team eliminates another team, it inherits its targets. Participants only know who they’re targeting, not who’s targeting them.

Goggles can provide protection.

Brighton Narvaez

And it gets more complicated. There are purge days, when no one is allowed to wear their goggles or floaties. On those days, all participants are required to have their Snapchat maps location turned on so that others can see where they are. “It’s a day to get a lot of people out – or drive to Wyoming,” Mucharsky jokes.

Because Filippini wanted to play, she recruited some East High juniors to assign targets and run the Snapchat; that way, no one can accuse her of having privileged information. She maintains the Instagram and bounty list, though. The Instagram features documentation of every “kill,” which only counts if there’s video evidence of the target getting hit.

Filippini collected a $10 entry fee from each participant; the total will be given to the winning team after a small amount is deducted to pay the juniors who help run the game. But students aren’t playing for the money; they’re playing for fun and tradition. Mucharsky says she still remembers hearing stories about who won in 2017, before she even started at East.

Community building is a key part of Assassin at East High.

Ruby Leuthold

Although Filippini is committed to keeping the tradition alive, she wanted the game to be more equitable. In the past, participants were charged $20 and students could pay more to play in more exclusive divisions, she notes. She didn’t want cost to be a barrier, and she wanted to prioritize the unity that the game could bring to members of a senior class who had spent so much time apart, so she went with a flat $10 fee and one big game.

“When we look at the list, we’ve included people from every group, every walk of life,” Mucharsky says. “Our school is unique because it’s so diverse, and I think that that’s really shown in everything we do, including our Assassin game.”

Even with help from the juniors, running Assassin is a lot of work – often thankless work. School administrators don’t always appreciate the game because of safety concerns, including the possibility that a squirt gun could be mistaken for a real gun. (East High administrators did not return numerous requests for comment.)

Filippini says she was called to the dean’s office when East administrators heard that she was planning to reintroduce Assassin, but after several safety tweaks to the rules, school officials felt less apprehensive about the game. Those rules include a provision banning any “kill” where either participant is in a moving vehicle, and maintaining the tradition that labels East High grounds a safe zone, including the walk from the parking lot to the buildings. Athletic and club events, both at East and other schools, are also safe zones, as are houses of worship and workplaces.

Participants never leave their cars without putting on protection.

Annabel Filippini

That last rule comforted Mucharsky’s mother, who was concerned that it would be bad for her daughter, who works as a lifeguard, to wear floaties while manning the pool.

“We kind of tried to alleviate the places where it would be distracting or harmful to be wearing goggles or floaties,” Filippini says.

Some teachers get annoyed because students don’t want to talk about anything other than Assassin, but others appreciate the injection of school spirit. Mucharsky reports that one student who didn’t come to school much first semester is in class more often now, always with goggles in tow. “Just seeing another person with goggles, you have a connection with them,” she says. “There’s something to talk about, which is great. I’ve definitely…had conversations with people that I hadn’t had conversations with since before the pandemic.”

Filippini’s experience has been similar, and people approach her in the halls to thank her for setting up the game. The only people from whom she’s received negative feedback are upset that they were eliminated. “There are complaints when people don’t think that they got out, but other than that, everyone has just absolutely appreciated our time,” she says. “It’s been awesome.”

The two friends say they’d do “anything for the game,” and that definitely involves detective work. Filippini says that playing Assassin can be stalkerish but fun. A player will follow a student home from school in hopes of catching the target off-guard, or attend sports practice or club meetings in case a target forgets to put protection back on when the event is over.

More than 200 seniors signed up.

Ruby Leuthold

Filippini says she sat outside of someone’s house for 45 minutes every morning for a week, with no luck. A friend thought about getting younger siblings to dress as Girl Scouts and ring the doorbells of participants’ homes under the guise of selling cookies, but has yet to test that strategy. And Mucharsky’s eleven-year-old brother keeps pranking her by pretending that Assassin players are outside their home with squirt guns.

As time goes on, Filippini and Mucharsky suspect that the antics will get wilder, because only those who are extremely dedicated will survive for long. In the meantime, though, Filippini hopes that everyone who encounters the players will understand that the game is all in good fun.

“I’m not excited for prom, or graduation, or spring break,” Filippini says. “I’m excited for Assassin, and I have been since eighth grade.”