Kevin J. Beaty

Audio By Carbonatix

In the vast scheme of things, $5,000 isn’t a lot of money. In the vast scheme devised by the Colorado Department of Transportation to expand I-70 through a ten-mile stretch of northeast Denver and Aurora, at a projected total cost of around $1.8 billion, five thousand bucks won’t even pay for two linear feet of one lane of highway construction.

But for folks living adjacent to the highway project, a recent $5,000 grant awarded to the Elyria and Swansea Neighborhood Association by a national environmental-justice advocacy group represents the beginning of something. The ESNA is one of several grassroots groups concerned about the highway project’s impacts on some of the most economically disadvantaged neighborhoods in Denver — which are also reputedly located in the most polluted zip code in the country. Wary of official claims that the project is necessary and environmentally safe, community activists hope to use the funds awarded by the Center for Health, Environment & Justice to aid in gathering independent research on health and safety issues raised by the construction.

Think of it as seed money. ESNA president Drew Dutcher says residents of the area have long felt frustrated at being outspent and overwhelmed by the fleets of consultants, media coordinators, community liaisons and other well-paid professionals employed by government agencies to win support for the highway makeover. “The City of Denver and CDOT can spend millions of dollars to sell this project to the neighborhoods,” he says. “But there have never been any resources, not one damn dime, available for anything coming out of the community. We’re all supposed to just volunteer our time and sign off on the result.”

The money from CHEJ, which is based in Falls Church, Virginia, “is a start,” Dutcher says. “We just don’t have the comfort level to trust the city, the EPA, or CDOT to look out for us. We’re going to do some things to assert what our rights are, and the grant can supplement those efforts. There’s an existing group that’s been gathering data, and we hope to raise funds for more of that. ‘Citizen science’ is a good way to characterize it.”

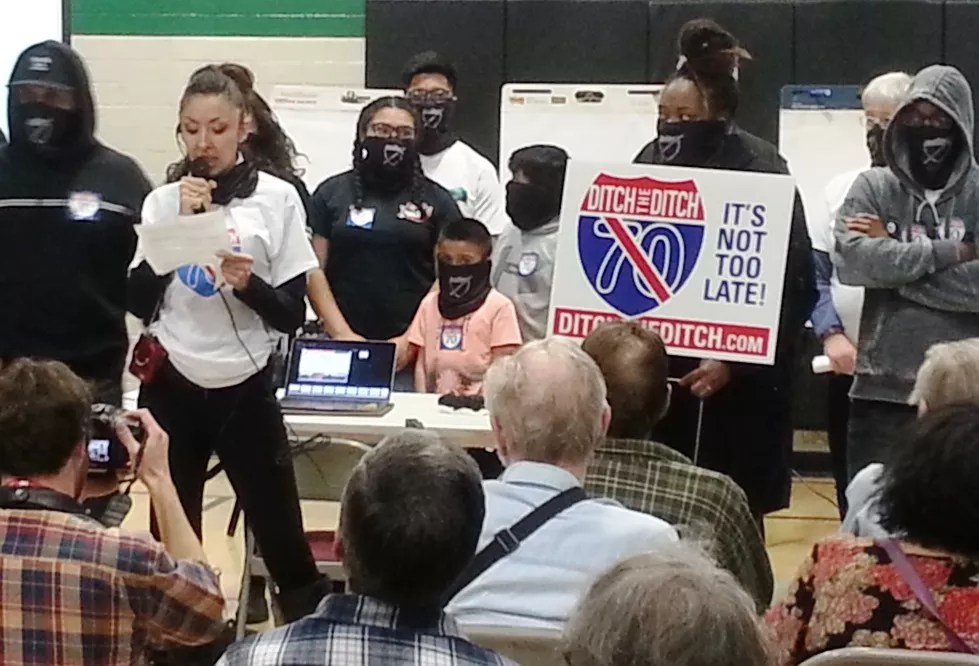

Protesters blasted the highway project before CDOT officials could convene a community meeting at the Swansea Recreation Center in February.

Alan Prendergast

The expansion project, which received a green light from the Federal Highway Administration earlier this year, focuses on a congested stretch of I-70 between I-25 and Chambers Road. It would replace a crumbling six-lane viaduct with a below-grade, partially covered superhighway expanded to ten lanes; officials say that a four-acre “lid” of greenery on top of the highway as it moves through the Elyria and Swansea neighborhoods would help reunite communities that were disrupted by the viaduct construction in the 1960s.

But some local residents believe that the project will only create further disruption and environmental hazards in the area. The Sierra Club has joined with community groups in north Denver to file a federal lawsuit against the EPA, claiming that the agency lowered its pollution standards in order to push forward the expansion. Other groups have complained that the project disproportionately impacts predominantly Hispanic communities, or are fighting a massive drainage project in Denver that will benefit the expansion but will also have less-than-ideal impacts on neighborhoods well beyond the I-70 corridor.

One critical component of the drainage project involves directing storm runoff to the South Platte River through a heavily polluted Superfund site, a process that some fear could expose the river and nearby neighborhoods to a toxic brew of contaminants from arsenic-laced groundwater and a long-buried landfill. Several Globeville residents serve on a community advisory group formed by the EPA that is supposed to address local concerns about the outfall and other construction issues, but Dutcher, who’s also on the CAG, says the group’s progress so far hasn’t been reassuring.

“It’s a little frustrating,” he says. “It’s still the show of the EPA and the city. We’re being spoonfed the information they want us to have.”

Five thousand bucks is, of course, not enough cheddar for Dutcher’s group to conduct extensive soil testing or otherwise replicate the sort of exhaustive analysis that the project’s supporters say has already been done. But it’s enough to engage in some fact-checking, data gathering and outreach, Dutcher insists. It’s enough, for example, to help raise questions about how the below-grade design became the “preferred alternative” for the project; although some residents had pushed for a tunnel at one point in the community outreach process, that option was abandoned in the draft environmental impact statement prepared in 2008 because “it would require building the highway through the South Platte River [basin], resulting in unacceptable effects on aquatic and ecological resources and increased potential for encountering contaminated groundwater and soils.”

Dutcher says it’s been a struggle for ESNA to find any official support in its quest to learn more about the project and its risks. He has e-mails dating back to 2015 requesting aid from city officials, including Kelly Leid (then in charge of the National Western Center expansion), to help the neighborhood groups deal with the onslaught of so many construction projects in what Mayor Michael Hancock has dubbed “the Corridor of Opportunity.”

“After several months of appeals to Kelly and his staff on this, we concluded there was nothing the city was going to do to help residents on a grassroots, community representation/planning level,” Dutcher says. “Isn’t it ironic that we have to go out of state to get help?”