Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection, Colorado State Library

Audio By Carbonatix

At the Denver Theater, the Ladies’ Relief Society passed out New Year’s gifts to poor children. There were well-attended “hops” at Guard Hall and the Inter-Ocean Hotel. At midnight, as bells rang out in celebration of the nation’s Centennial, the men of the J.E. Bates Fire and Hose Company rang theirs so hard it cracked.

But the place to be in Denver on New Year’s Eve 1875, according to William Byers’ Rocky Mountain News, was at the music hall recently opened by the city’s Maennerchor, or “men’s chorus,” a singing social club formed by members of its large German-American population.

“The Maennerchor ball was the big thing of last night, at their new hall,” reported the News of January 1, 1876. “Everybody and his wife or sweetheart was there. They remained long after the bells rang in the Centennial morn.”

Not quite everybody: Forty people began the New Year as inmates in the Arapahoe County jail, the News reported, and by the end of 1875 there were some 4,000 children enrolled in Denver’s public and private schools.

They were among a city population that had reportedly quadrupled in the previous five years to an estimated 20,000, and Denver’s numbers had swelled further in recent days and weeks. Members of the territorial legislature, along with delegates to its constitutional convention, were arriving from cities, towns and mining camps across the soon-to-be state. Colorado’s boosters claimed the territory’s population had reached 150,000 by 1875, though credible sources considered that an “extravagant” estimate.

“From daylight in the morning until midnight, little caucuses of from two to six gather at the hotels, restaurants, beer halls, street corners and other nooks and corners, to lay their plans for the coming events,” a correspondent from Denver wrote to the Pueblo Chieftain.

City, county and territorial offices were all closed on January 1. Both the News and the Chieftain, which cited “one of the few holidays allowed newspaper men and printers,” told readers no paper would be issued on January 2. The day off was an important social occasion for Denver’s burgeoning elite, and the News carried a “list of the ladies who are to receive New Year’s calls,” including the family of its publisher: “Mrs. Byers and her daughter, Mamie, assisted by Mrs. Judge Wells, the Misses Parcells and Miss Alice Hill, will receive from 12 (p.)m., at residence on Capitol Hill.”

Despite sub-zero temperatures, a revelrous atmosphere had descended on Denver as 1876 began — “the foundations of many Centennial headaches were liberally laid,” the News reported — and showed no signs of letting up for the holiday.

“It is believed that some few gentlemen, contrary to custom, will keep sober, but this announcement cannot be made authoritatively,” quipped the News.

Denver’s fifty-odd saloonkeepers had recently colluded to fix the price of beer at ten cents a glass. To make their way from one watering hole to the next, Denverites could pay a fare of a nickel to ride the City Railway, a horse-drawn streetcar with tracks that ran on Broadway, Champa and 23rd streets.

Alongside the saloons, a city directory published in early 1876 contained listings for 22 hotels, four billiard halls, 54 grocers, three gun shops, three music shops, nine banks and nine newspapers, including William Witteborg’s German-language Colorado Journal. Two businesses that would last well into the twentieth century, Joslin’s and Daniels & Fisher, were among the city’s five purveyors of dry goods. J.H. Vandeventer and T.H. Sanborn ran competing laundries downtown, while one Gustav Steup, at 114 15th Street, advertised his services as the city’s lone mustard maker.

In Pueblo — the Colorado Territory’s second city, with about 6,000 inhabitants — the main New Year’s entertainment was a day of horse racing at the fairgrounds. In the day’s final race, O.S. Sheldon’s Bay Billy beat John Davis’ Buckskin Joe to claim the $50 prize, but the real action was in the crowd, where “pool selling was lively and considerable money changed hands.”

Around the Territory

Outside of Denver and Pueblo, Colorado’s next-largest population center was located in the gold-mining districts of Gilpin and Clear Creek counties, where for fifteen years fortune seekers had flocked to stake claims or ply their wares in towns like Central City, Black Hawk, Idaho Springs and Georgetown. Since 1873, the region had been served by the Colorado Central Railroad, which allowed passengers to travel between Denver and its Floyd Hill terminus in two hours and 45 minutes.

Passengers could also step onto a train in Denver and step off into many of the small settlements — Boulder and Greeley to the north, Castle Rock and Colorado Springs to the south — that would grow into today’s Front Range urban corridor.

But in 1876, most of the rest of Colorado was still a long way from looking like it does today. Even in the San Luis Valley — the first part of the territory to have been settled by non-native people, Hispanos from New Mexico who arrived there in the 1840s — the town of Alamosa wouldn’t be founded for another two years. The Eastern Plains, where the Army and territorial militias had waged a bloody campaign against the Cheyenne and Arapaho that ended with 1864’s Sand Creek Massacre, were still largely deserted.

Most notably, under the terms of an 1868 treaty, nearly half of the territory west of the Continental Divide was still reserved for the Ute people, though they had recently been pressured into ceding a large portion of the mineral-rich San Juan Mountains, where a silver rush was underway. Grand Junction, Durango, Aspen, Gunnison and Glenwood Springs were among the many Colorado communities that didn’t yet exist.

The territory’s westernmost settlement in today’s Interstate 70 corridor was the tiny hamlet of Breckenridge, home to about 250 people. It had no newspaper, and bad weather and delinquent postal contractors could cause weeks-long delays in the mail arriving over snowy mountain wagon roads. Though it was a long way from Denver and its bustling nightlife, a Breckenridge resident wrote to Georgetown’s Colorado Miner to report its happy holiday mood.

“Quite a lot of jolly folks are in town this winter, and ladies enough to have a dance almost any time,” wrote the correspondent. “We have, once or twice each week, some nice music and singing at Mr. Ballou’s, and on Sunday evening church services. Our winter will pass without noticing it.”

Road to Statehood

The eleventh and final session of the Territorial Assembly — consisting of a 13-seat upper chamber called the Council, and a 26-seat House of Representatives — convened in Denver on January 3. John Long Routt, the former Union infantry captain appointed governor the previous year by President Ulysses S. Grant, addressed the Legislature in a written message two days later.

“The progress Colorado has made during the past 15 years has excited the attention of the civilized world,” Routt wrote. “Let the efforts of all be generally directed to the furtherance of Colorado’s admission into the Union, when through the intelligence, energy and wealth of her people, she may be among the first of the states, as she has been first of the territories.”

After more than a decade of trying, territorial leaders entered 1876 confident that Colorado would soon enter the Union as the 38th state. An enabling act passed by Congress and signed into law by Grant in March 1875 had begun the process, instructing the territory to convene delegates to draft a state constitution and hold a popular vote ratifying the document by July of the following year.

As the enabling bill had made its way through Congress, and the timeline for Colorado’s long-awaited statehood came into view, an obvious nickname presented itself. Though Byers and the News would claim to have been the first to suggest it, it was in fact the rival Denver Times that first printed the words on February 27, 1875.

“The delay in admission will prove no serious drawback to Colorado,” wrote the Times. “Colorado will be admitted upon the centennary of American independence, and will in the future be known as the ‘Centennial State.’”

Selected Sources

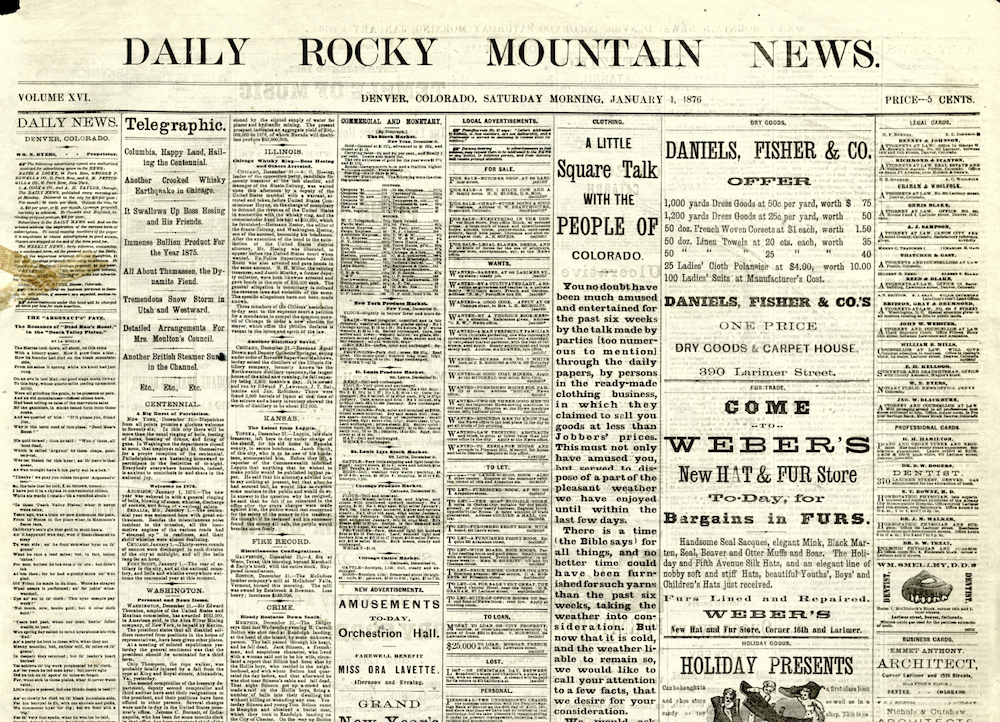

- The Rocky Mountain News (Daily), December 31, 1875–January 6, 1876

- The Colorado Daily Chieftain, January 1–4, 1876

- The Colorado Miner (Weekly), January 1 & 8, 1876

- Corbett, Hoye & Co., “Fourth Annual City Directory,” 1876

- Frank Hall, “History of the State of Colorado, Vol. II,” 1890

This story was originally published by Colorado Newsline, and is part of Colorado at 150, featuring special reports on the people and history that define the state. Colorado Newsline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity.