U.S. Postal Service

Audio By Carbonatix

The road to death is a long march beset with all evils, and the heart fails little by little at each new terror, the bones rebel at each step, the mind sets up its own bitter resistance and to what end? The barriers sink one by one, and no covering of the eyes shuts out the landscape of disaster, nor the sight of crimes committed there.

The reporters and editors are in the newsroom, debating whether they have to donate to a publisher’s pet cause – “I wonder if a threat like that isn’t a kind of blackmail” – while also talking about the opening of a new cabaret in downtown Denver; learning from an editor that you should “never say people when you mean persons…and never say practically, say virtually, and don’t for God’s sake ever so long as I am at this desk use the barbarism inasmuch under any circumstances whatsoever”; and wondering about the source of a plague that was suddenly hitting people around the world, like “something out of the Middle Ages. Did you ever see so many funerals, ever?”

The reporters discuss whether the disease could have come by ship, maybe into Boston, where germs might have been “sprayed over the city.”

“I read it in a New York newspaper,” says one reporter, “so it’s bound to be true.”

As for herself, she had too many pains to mention, so she did not mention them. After working for three years on a morning newspaper she had an illusion of maturity and experience; but it was fatigue merely, she decided, from keeping what she had been brought up to believe were unnatural hours, eating casually at dirty little restaurants, drinking bad coffee all night, and smoking too much.

Except for the substantial size of that Denver newsroom, and the fact that there are competing dailies around town (so many that they’re differentiated by “morning,” “afternoon” and “evening”), that conversation could be happening today, as journalists debate just how to cover what started out being referred to as the coronavirus, inspiring jokes about Mexican beer, then grew to the deadly serious COVID-19. By mid-day March 9, there were nine presumptive positive cases in the state of Colorado, with more than 550 around the country; 22 of those had resulted in death.

But that scene, those italicized lines, date back a century ago, when the influenza pandemic – the “Spanish flu” that may have actually originated in Kansas – first began surfacing with military personnel in the spring of 1918, ultimately killing up to 675,000 Americans (1,500 of them in Denver), and as many as 50 million people worldwide; an estimated 500 million people (or was that persons?) were infected with the virus before the epidemic ran its course by 1920.

The young Porter.

humanitiestexas.org.

https://ia801602.us.archive.org/2/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.184599/2015.184599.Pale-Horse-pale-Rider.pdfhttps://ia801602.us.archive.org/2/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.184599/2015.184599.Pale-Horse-pale-Rider.pdf One of them was Katherine Anne Porter, a reporter at the Rocky Mountain News. Born in Texas in 1890, she’d moved to Chicago to become an actress in 1914, then returned to Texas, where she spent two years recovering from bronchitis in a sanitarium. There she started writing a gossip column and trying her hand at theater criticism, which earned her a job at the News. Then she came down with the flu. There were no beds in the local hospital, and her fiancé, an Army lieutenant she’d only known for a short time who was waiting to be shipped overseas, helped care for Porter in her rooming house on Marion Street. She was so sick that the paper “had my obit set in type,” she later told a reporter. “I’ve seen the correspondence between my father and sister on plans for my funeral….”

By the time Porter recovered, her hair had turned white. Her fiancé had perished in the epidemic.

Adam said soberly, after a moment, “Oh, yes, but suppose one does come back whole? The mind and the heart sometimes get another chance, but if anything happens to the poor old human frame, why, it’s just out of luck, that’s all.”

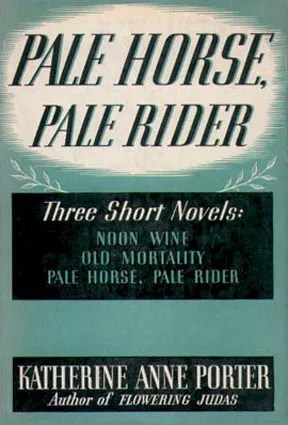

Porter soon moved on from Denver, but she recounted her near-fatal experience twenty years later in “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” a novella named after an old spiritual in which she is “Miranda,” her never-actually-identified fiancé “Adam.” It was included in a collection of short stories of the same name, but by far the most famous is “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” a harrowing, hallucinatory piece that generations of high school students across the country were required to read, then promptly forgot.

The first edition.

Harcourt Brace

Still, this story, published more than forty years before Porter really did pass away, is worth resurrecting. Its feverish, century-old stream-of-consciousness tale is oddly reassuring in a world again turned upside down by dizzying unknowns, even though the Internet has now made it possible to get the latest rumors almost instantaneously, rather than having to wait for daily newspapers to dish up their pieces based on week-old communiqués and stories in New York newspapers. It was an epidemic of horrifying dimensions set against the War to End All Wars. Yet somehow, life did go on.

As “Pale Horse, Pale Rider” concludes:

No more war, no more plague, only the dazed silence that follows the ceasing of heavy guns; noiseless houses with the shades drawn, empty streets, the dead cold of tomorrow. Now there would be time for everything.

In case you’re not frequenting libraries or bookstores these days, you can download this open-source PDF of “Pale Horse, Pale Rider.”