Audio By Carbonatix

The Massachusetts Supreme Court has ruled that a company acted improperly when it fired medical marijuana patient Cristina Barbuto after she tested positive for pot. The Colorado Supreme Court reached the opposite conclusion in an analogous 2015 case, determining that DISH had the right to dismiss paralyzed MMJ patient Brandon Coats following his own positive test for cannabis. And while the Barbuto finding won’t directly impact the Colorado case, Coats’s lawyer sees a trend toward granting more patient protections here and in other medical marijuana states.

“The Colorado Court of Appeals just came out with their first decision on the smell of marijuana from a car not meeting probable cause standards,” notes attorney Michael Evans, corresponding via e-mail. “This is good, and logical. But it took forever for Colorado to get a case on this. Why?”

Such questions have been asked plenty of times since we first told Coats’s story more than five years ago, including by Last Week Tonight host John Oliver, who spotlighted the Colorado ruling in his shredding of dubious marijuana laws during a broadcast this past April.

As we’ve reported, Coats, who’s in his thirties, is paralyzed over 80 percent of his body. At age sixteen, he was a passenger in a vehicle that crashed into a tree.

Since then, Coats has used a wheelchair to get around, but he’s fully capable of working – and in 2007, he was hired by DISH as a customer service representative. Over the next couple of years, his original lawsuit contended, prescription medicine Coats took to treat involuntary muscle spasms began to fail. When searching for a way to deal with these symptoms, his physicians recommended that he supplement his regimen with medical marijuana. He received his state-issued license for MMJ in August 2009 and found that cannabis helped alleviate his spasms. However, the complaint stressed that he never used marijuana at his job during work hours or anywhere on the company’s premises.

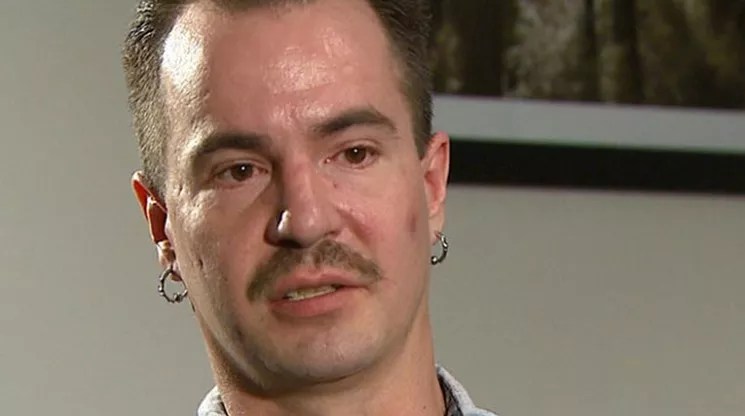

Attorney Michael Evans and client Brandon Coats.

File photo

In May 2010, Coats was ordered to take a random drug test. He’s said to have told the employee administering the test that he was an MMJ patient, but this wasn’t taken into account when he registered a positive for THC. The agent who broke the news allegedly told him that his status as a patient didn’t matter: “That is just Colorado state law and does not apply to your job.” Two weeks later, Coats was fired for violating the company’s drug policy.

Evans took DISH to court, arguing that Coats’s activities were constitutionally protected. But in February 2012, Araphaoe District Judge Elizabeth Beebe Volz granted DISH’s motion to dismiss. Among the cases she cited to justify this ruling was one involving Jason Beinor, a medical marijuana patient sacked from his street-sweeping job for failing a drug test.

After more judicial machinations, the Coats case reached the Colorado Court of Appeals. But in a 2-1 decision, the court sided with DISH, and the Colorado Supreme Court wound up concurring.

“By its terms,” the CSC ruling states, “the statute protects only ‘lawful’ activities. However, the statute does not define the term ‘lawful.’ Coats contends that the term should be read as limited to activities lawful under state statute. We disagree. We find nothing to indicate that the General Assembly intended to extend section 24-34-402.5’s protection for lawful activities to activities that are unlawful under federal law. In sum, because Coats’s marijuana use was unlawful under federal law, it does not fall within section 24-34-402.5’s protection for ‘lawful’ activities.”

Brandon Coats circa 2015, when the Colorado Supreme Court ruled against him.

CBS4 file photo

Contrast that with the opinion of Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Justice Ralph Gants on behalf of Barbuto, who uses medical cannabis to treat symptoms of Crohn’s disease. As noted by the Boston Globe, Gants stated that “the use and possession of medically prescribed marijuana by a qualifying patient is as lawful as the use and possession of any other prescribed medication.” For that reason, he determined that employers such as Advantage Sales and Marketing, the California-based concern that sacked Barbuto, aren’t allowed to use so-called blanket anti-marijuana rules against employees whose doctors have recommended the substance.

Evans points out that “similar arguments were made by DISH in an appellate case against another terminated MMJ patient-employee,” Charles “Sonny” Meyers. In that case, a majority of judges found no evidence that “Meyers knew, or reasonably should have known, that DISH’s purported drug policies prohibited its employees from reporting to work or being at work with any detectable amount of marijuana in their system.” (Click to access that case, Meyers v. Industrial Claim Appeals Office and Echosphere LLC.) He adds that “DISH’s policy was not made part of the record in Meyers…. Notwithstanding, the Courts of Appeal determined that the alleged policy that existed in 2009 for Colorado-based DISH did not identify nor define ‘prohibited’ drugs – specifically in relation to marijuana. Mr. Coats worked for DISH between 2007 and 2010, and therefore the same alleged defunct policy in Meyers could have arguably existed at least the last year of Coats’ employment.”

Whatever the case, Evans continues, “I still maintain, and so do many other lawyers, that our state supreme court was not ready or willing in Coats to challenge federal law under the U.S. 10th Amendment – which reserves decision-making power of all unenumerated rights (those not specifically listed in the US Constitution) to the states. A more aggressive, risk-taking court would have done that – and defended their own state constitution, as their oath of office so states they will. They would have been the first in the world to do so, not just the U.S. Unfortunately, it is all too common for judges who reach the top of the food chain to be too conservative, not make waves or punt the difficult issues instead of taking them head on.”

In Evans’s view, “I would think if one reached that level of decision-making power in their legal career, they would do what is right even if it is difficult – not what is safe.”