Jake Holschuh

Audio By Carbonatix

Jake Holschuh

Denver Deputy Sheriff Melis Ibisevic was busing tables at the Chili’s on the 16th Street Mall for a Special Olympics charity event this summer when someone ran into the restaurant and said that a man had just jumped off a nearby roof.

Ibisevic ran outside. The man appeared to be dead, but he and his partner started applying tourniquets, and he began administering CPR. They worked on the man for over ten minutes before other first responders arrived.

“The guy didn’t make it, even though we tried our best and gave it all we had to attempt to save this man,” Ibisevic remembers.

His efforts did not go unnoticed. On February 21, the 29-year-old will receive a Sheriff Commendation Award at an annual department awards ceremony.

But it’s not just his first-responder instincts that make Ibisevic stand out in the sheriff’s department.

He came to this country as a refugee; when he was a young boy, he lived through war and genocide in his home country of Bosnia. Unlike many of his family members, including his police officer father, Junuz, he survived the violence and eventually came to Colorado.

And it was here that he decided to follow in his father’s footsteps.

The Ibisevics fled their village, like other refugees in Bosnia in the early ’90s.

Spencer Platt/Getty Staff

Melis Ibisevic was born in September 1990 in a small village on the outskirts of the Bosnian town of Srebrenica, just as the Balkans were splitting apart. Famous as an intersection point for different religions and cultures, the Balkans were losing the political unity that the region had enjoyed for decades. And as political unity disappeared, ethno-nationalist politicians gained power. These leaders were quick to turn neighbors into enemies.

“‘Turks’ became a derogatory way of talking about Muslims,” says Marie Berry, a professor at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. Military leadership among the Orthodox Christian Bosnian Serbs weaponized phrases like that to stoke hatred toward Bosnian Muslims, including the Ibisevic family.

Yugoslavia, a multi-ethnic, multi-religious communist country bordered by Italy, Austria and Greece, was disintegrating, and its citizens were fighting each other for land and sovereignty. With support from the remnants of the Serbian-dominated Yugoslav government in Belgrade, Bosnian Serbs started to fancy the idea of a greater Serbia that linked much of the land in Bosnia to the rest of the majority-Serbian land. With violence spreading throughout the region, military-aged men in Bosnia took up arms.

Junuz Ibisevic, a career police officer, joined the Bosnian military in the early 1990s, just as Bosnian Serbs began fighting Bosnian Muslims.

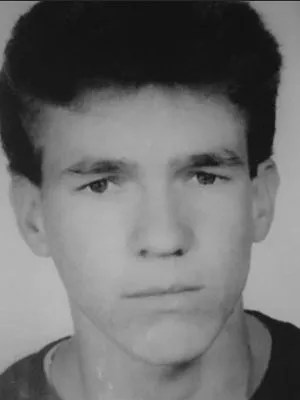

The only photo left of Junuz Ibisevic, when he was a young police officer.

courtesy of Melis Ibisevic

In May 1992, as Bosnian Serb forces were advancing, the Ibisevic family fled their village. This offensive by Bosnian Serb soldiers and paramilitary units kicked off a series of ethnic-cleansing operations that would culminate in the worst genocide in Europe since World War II. For the next three months, the family lived in caves in the mountains. That August, they navigated their way through booby-trapped fields and mountains to Srebrenica, where the United Nations had stationed a peacekeeping force. The next year, the U.N. declared it a “safe area.”

Still, life was difficult. Despite having a roof over their heads — the Ibisevic family lived on the bottom floor of a defunct bar — food was hard to come by, and there was little medical care. “Every day was about survival,” says Mina Ibisevic, Melis’s mother, as her son interprets. “You wake up in the morning and would have to come up with a plan as to what you’re going to eat today.”

She adds in English: “If you find one zucchini, you’re rich.”

With entrances to the town cut off by Bosnian Serb forces, the United States led efforts to air-drop food and medical supplies into Srebrenica. But those attempts only went so far, as the population of Srebrenica had swelled from 8,000 to about 60,000 with all of the refugees from the surrounding region, according to Human Rights Watch.

Mina had to figure out meals that would feed over a dozen people. There was Melis and his sister, Minela, as well as an uncle whom Mina’s mother had adopted years before, another uncle and his wife and their two kids, another aunt and her husband, and Junuz’s parents. Family members would all sleep on the same mattress.

“You pretty much lay down and everyone puts their upper body and their head [on the mattress], but the lower body, where it doesn’t hurt as much, you’d be on the floor,” she remembers. “And everybody would line up in one line, and that’s how everybody sleeps.”

Mina washed clothes using boiling water to kill any bacteria. One night when Melis was around two and a half years old, she was doing laundry in a pot of boiling water that she’d set up in the middle of their living space. The lights went out as part of a blackout, a common occurrence in besieged Srebrenica.

“I freaked out, so I was running toward my mom’s voice, and I ended up falling into that boiling water,” Melis says. “My whole left leg…all they had to do was remove the sock, and with the sock, all the skin came off.” His mother put milk on his leg to soothe the burns.

Although Melis doesn’t actually remember the details of the incident, he’s reconstructed it from what his mother and other family members have told him. “Later on, they put some potato skins on there just to keep it covered so infections didn’t arise, because gangrene was very big,” he adds.

While civilians struggled to make ends meet, some of the able-bodied men in Srebrenica, like Junuz Ibisevic, participated in hit-and-run operations. They held off the Bosnian Serb advances until July 1995, when soldiers broke through into Srebrenica.

Despite a promise from the U.N. that Srebrenica would be a “safe area,” members of the peacekeeping force either surrendered or withdrew from the advancing cadre of Bosnian Serb soldiers. “It’s the moment that the U.N. lost any form of moral credibility,” notes Berry.

On July 11, Ratko Mladic, the man leading the Bosnian Serb forces, walked through Srebrenica and said on camera, “We give this town to the Serb nation. … The time has come to take revenge on the Muslims.”

Junuz Ibisevic disappeared that day. As a military man, he knew he was sure to be killed if he stayed, so he ran into the woods, trying to escape Srebrenica with his two brothers, his sister and her husband.

His uncles later told Melis what had happened. His father was holding his sister’s hand when there was shooting and an explosion went off, and “something happened, like they dropped to the floor,” Melis says. “It’s not proven that that’s when he got killed. … That was the last time they ever saw him alive.”

Melis considers his father a hero: “He was protecting them when those shots rang out.”

Junuz Ibisevic’s body was found in a mass grave, like this one near Srebrenica.

Sean Gallup/Getty Staff

Bosnian authorities identified Junuz Ibisevic’s body in a mass grave about a decade ago. “According to the autopsy, there were bullet holes through his rib cage, his head, and his legs were missing. He didn’t have his legs,” says Melis.

“Only half of head,” his mother adds in English.

While Junuz Ibisevic was running from bullets that day, Melis and his sister, his mother and other family members were sent by Bosnian Serb soldiers to an old car battery factory, where soldiers separated the women and children from the men. “That’s actually when they took my grandpa from us,” Melis remembers. “He was executed, I believe, like right down the street.”

In the days that followed, other men and boys were rounded up, blindfolded and executed by Bosnian Serb soldiers. By the end of what the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia later declared a genocide, at least 7,000 men and boys had been executed. Mladic was eventually found guilty of genocide and sentenced to life in prison.

While these mass executions were taking place, Melis, his sister and his mother were loaded onto a truck and sent to Bosnian-controlled territory. On that truck, a teenager asked Mina if she could hold Minela and pretend that they were mother and daughter. “If they saw that she wasn’t married or had kids, there was a possibility of her getting taken off the truck and God knows what would happen,” Melis says.

Eventually, the Ibisevic family, minus many of its members, made it into territory controlled by Bosnian Muslim soldiers. They moved into a school in the city of Tuzla and stayed in a corner of a classroom for about three months, along with several other families. After that, they moved into an abandoned house and slept on cardboard boxes for about four months, Melis recalls.

Then the family had a lucky break: A man offered them his fully furnished vacation home in the town of Serici, where they lived for two years before moving on to Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. “At this point, life was getting stable,” Melis explains. “The war had been over for a couple years.”

But life wasn’t the same. They’d fled the town where their family had lived for decades. Junuz was gone. And so in 1999, Mina applied for resettlement for the family in the United States as refugees.

Melis Ibisevic and his mother, Mina.

Jake Holschuh

The refugee resettlement process, which involves intense vetting, can often take years. The Ibisevic family waited three years before they received final authorization to be resettled in the U.S.

On July 9, 2002, eleven-year-old Melis arrived in Denver along with Minela, Mina, and Melis’s uncle Hajrudin.

They were picked up at the airport by staffers from the African Community Center, a local refugee resettlement agency. No one in the family spoke or understood English, and they didn’t know a thing about where they had just moved.

“I remember my uncle sitting in the back, and he’s like, ‘Where are we?,’” Melis recalls. But then the tall buildings of downtown Denver appeared on the horizon.

“Then life started happening,” says Melis, who remembers thinking, “Oh, my God, it’s like the movies. The big cities, the big highways.”

From 1993 through 2003, over 2,000 refugees from Bosnia were resettled in Colorado, according to the Colorado Department of Human Services. Since there was already a sizable Bosnian community in the metro area, the African Community Center resettlement staff made sure to place the Ibisevic family in a Lakewood apartment building that housed another Bosnian family. When they walked into their new home, they saw a welcome note from the other family.

Mina quickly got a job cleaning at a casino in Black Hawk, then moved on to a job as a custodian at Denver Health.

Melis was enrolled in a sixth-grade class at a public school in Lakewood; Minela started out in eighth grade.

They were both immediately enrolled in English as a Second Language courses. And despite not knowing English at all, Melis took to school quickly. “Comparing the schooling system in Bosnia to here is night and day,” he says. “They actually work with you, which I loved.”

“The principal came up to me and said, ‘Hey, what do you want to do when you grow up?’”

Melis graduated out of the ESL curriculum at the end of ninth grade. Then, during his sophomore year at Lakewood High School, he recalls, “The principal came up to me and said, ‘Hey, what do you want to do when you grow up?’”

“I always wanted to be a cop,” he responded. Like his father.

“The stories mom tells me of, ‘You’ll be like a superhero, you’re protecting people, saving lives…’ — that’s really what inspired me,” he says now.

Not long after, the principal called Melis into his office and told him about the Youth Police Academy, a week-long summer program for high school students aspiring to be law enforcement officers.

Melis landed at the YPA in the summer of 2007. There, he and other students learned what it takes to work in law enforcement, including how to drive a police car. “It was cool. I had an amazing time,” recalls Melis.

Dutch Smith, one of the high school’s resource officers who’s a detective with the Lakewood Police Department, helped propel Melis’s dreams of a career in law enforcement.

“I really latched onto him at the school,” Smith says. “He just always seemed very interested in how this whole thing works. I went through the full gamut of the ups and downs of law enforcement. The rigors of the job, the public perception of what you do. And he always kept going at it and wanted to be more involved.”

Smith introduced him to the Lakewood Police Explorer Program, which gives 14- to 21-year-olds an immersion in law enforcement. Participants learn about community policing and investigative techniques, and even get to help out with events in the community. Explorers also participate in competitions with Explorer units from other states.

Melis got into the program at sixteen. As part of his training, he worked at Colorado Mills, helping parents track down lost children.

“It helps them become a better police officer. They perform much better in the academy,” says Sonja Gist, a Lakewood police detective who has been the head of the city’s Explorer program for seven years.

But Melis had to wait until he was at least 21 to apply for a law enforcement job. So after graduating from Lakewood High School, he studied criminal justice at Red Rocks Community College and worked a variety of jobs. At one point, he was a guard for an armored bank truck. At another time, he served as a volunteer firefighter in Edgewater. But he kept an eye on his ultimate goal: “Law enforcement has always been a dream.”

When he was 24, Melis decided he was ready to apply for a job in law enforcement. That happened to be when the Denver Sheriff Department was recruiting for its upcoming academy, a “mega class” of deputies that was part of then-Sheriff Patrick Firman’s efforts to get new blood into a department that had been plagued by embarrassing and costly in-custody deaths and use-of-force incidents.

Ibisevic was accepted, and graduated from the academy in mid-2016, when he was 25. He’s been working in the jail division ever since.

Melis Ibisevic speaking to Muslim youth about working in law enforcement.

Courtesy of Melis Ibisevic

Four years into the job, Ibisevic plans to spend the rest of his working days in the Denver Sheriff Department.

He works in what he refers to as a “floater” role. One day, he might be assigned to a jail pod for people charged with lesser criminal offenses. On another day, he might be working in a pod with people charged with felonies. In either pod, he’s responsible for the care and custody of inmates, feeding them and making sure there are no safety issues, like fires or fights. “You are the first responder on scene to deal with everything and make sure everything is running smooth,” he explains. “Yes, it’s stressful, and we deal with a lot of stress. But I love my job, so I just do it. I just deal with whatever is going on.”

When he’s not at work, he likes to invite neighbors over for barbecues in the back yard of the Lakewood home where he lives with his mother, who is recovering from cancer. His sister now lives in North Carolina with her husband. On Fridays, he’ll worship at a Bosnian mosque on Sheridan Boulevard.

“And they look at this guy and say, ‘Gosh, look at what I can accomplish.’”

Both on and off the job, Ibisevic relishes interacting with members of the community. That doesn’t happen often at the jail: “We’re not on patrol, so we don’t get a whole lot of community interaction,” he notes.

The mall incident this summer was an unexpected exception; an Employee Awards Committee made up of sheriff department staffers considered him for a commendation for his behavior that day. The sheriff reviewed all recommendations and determined the employees who will be honored on February 21.

A less dramatic opportunity to work with the public arose in December.

A friend asked if Ibisevic would speak at the Muslim Youth Empowerment Conference, an event at the University of Colorado Denver that’s essentially a career day for young Muslims, many of whom are immigrants, like Ibisevic. He jumped at the chance, but had to confirm one thing first.

He needed permission from his boss to wear his uniform to the event.

“When the deputies want to wear a uniform outside their official job duties, they need authorization,” explains Fran Gomez, who was named Denver’s interim sheriff last fall, after Firman resigned.

Gomez quickly approved the request from Ibisevic, who’d come to her attention after the incident on the mall this summer. “I love it,” he says. “I love to wear my uniform, love to put on my uniform…it’s just something I truly love. It’s a passion.”

Wearing that uniform, he made a quick stop on his way to career day. “I’m big on sense of humor,” he explains. “I love to have a good time and laugh, so I brought two things of doughnuts. And everyone thought it was hilarious. Even the kids.”

Ibisevic wound up interacting with a number of students that day who were curious about the sheriff’s department. He told them about Denver’s cadet program, which is somewhat like Explorers, except that participants get paid. He gave out his phone number to those interested in working in law enforcement. He shared his own experience as a newly arrived refugee adjusting to life in America.

“I migrated here,” he says. “One thing you have to do is you have to learn a culture, and now you’re adapting to that culture. [And then] you’re coming in to protect that culture. There’s a lot of things to think about.”

After the event wrapped up, Ibisevic emailed Gomez to tell her how many kids had stopped by and what a kick they got out of his doughnut gag.

Gomez realized that Ibisevic’s energy and experience could be useful tools for the department.

“He could reach so many people that maybe we haven’t reached in the past,” she says. “I’m trying to figure out other ways to get his face out there, get his story out there, and not just in law enforcement. If he can encourage a person that maybe didn’t feel like they’re a part of the American culture, maybe they feel distance. And they look at this guy and say, ‘Gosh, look at what I can accomplish.’”

At the beginning of the new year, the department even published a blog post highlighting Ibisevic’s refugee background. The piece mentioned his determination to follow in his father’s path.

“He would definitely be proud,” Ibisevic says. “He would definitely be proud.”