Quentin Young/Colorado Newsline

Audio By Carbonatix

“Without my family, I’m nothing,” read the subject line of an email sent by then-state Representative Gabe Evans to supporters on September 10, 2023.

The email announced Evans’ candidacy for Colorado’s toss-up 8th Congressional District, and it began with a story the Fort Lupton Republican has told countless times throughout his political career – the story of his grandfather, Cuauhtemoc Chavez, who was born in Mexico and earned U.S. citizenship through his Army service in World War II.

“My family fought tooth and nail for the American dream so that future generations like me could have a better life,” Evans wrote. “And I plan on making that up to them in full.”

As a rising star in the Colorado GOP and loyal supporter of President Donald Trump’s agenda in Congress, Evans has leaned heavily on his Mexican-American heritage and the man to whom he referred in a campaign launch video as his “abuelito Chavez.” Telling and retelling the story of his grandfather, who died in 2014, is Evans’ go-to means of putting a more moderate face on the historically extreme mass-deportation policies backed by Trump and his top advisers.

“We are a nation that is ruled by law,” Evans told moderators at a January 2024 debate, responding to a question about how “millions of people living in the U.S. illegally” should be treated. “You need to go stand in that line and do it the right way, do it the legal way, so you are not leapfrogging over those folks like my grandfather, who did it the right way and did it the legal way.”

But Evans has mischaracterized the story of how his Depression-era ancestors achieved the American dream, and misstated key dates and details in his grandfather’s biography, according to documents obtained by Newsline through archival research and government records requests.

Those records show that the Chavez family, and a young Cuauhtemoc in particular, were squarely on the wrong side of the “strong immigration policies” his grandson now invokes his name to champion.

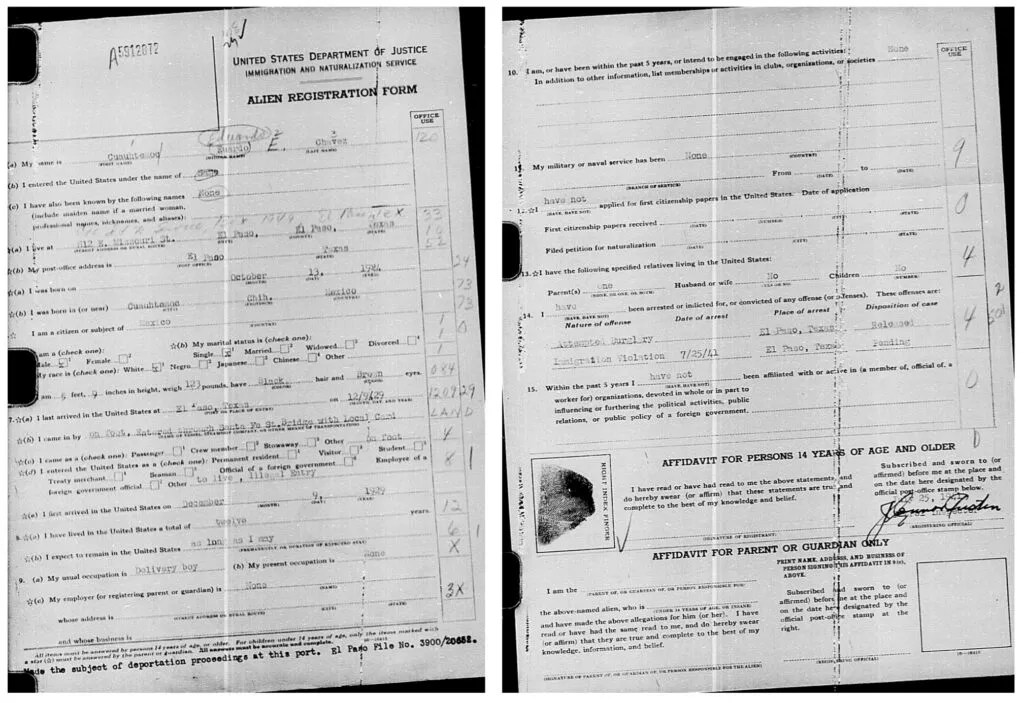

A 1941 Immigration and Naturalization Service document, obtained through a records request with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, shows that Cuauhtemoc entered the country unlawfully with his mother and siblings in 1929, at the age of five, and resided unlawfully in Texas for the next twelve years. The document, known as an alien registration form, or an AR-2, was prepared shortly after Cuauhtemoc, then sixteen years old, was arrested for an “immigration violation” in El Paso and “made the subject of deportation proceedings.”

At least two of Cuauhtemoc’s sisters were arrested by immigration agents on the same day, according to the nearly identical documents prepared for them. All three reported crossing the Santa Fe Sttreet Bridge into El Paso on December 9, 1929. Under a field for listing their reason for traveling to the U.S., the same typewritten words appear on all three documents: “to live, illegal entry.”

Cuauhtemoc’s AR-2 form also lists a prior, undated arrest for “attempted burglary,” placing the sixteen-year-old in a category of immigrants that Evans has said, without exception, should be deported. Evans was a vocal supporter of the Laken Riley Act, which was passed by Republican congressional majorities in January and requires federal immigration agents to prioritize the detention of any undocumented immigrant arrested for a “burglary, theft, larceny, or shoplifting offense.”

A 1941 Immigration and Naturalization Service form shows details of Cuauhtemoc Chavez’s unlawful entry in 1929 and his later arrest for an “immigration violation.”

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

In the weeks preceding publication of this story, Evans appeared to acknowledge or accept the assertion that his grandfather had entered the country unlawfully in at least two interviews. His office could not point to any examples of similar disclosures during the 2024 election or before. Delanie Bomar, his spokesperson, first claimed that Evans had been “very consistent” and “clear about his family’s story,” but subsequently said his past comments may have been “confusing.”

“In Hispanic culture, immigrating the ‘right way’ generally means working hard, contributing to their community, and not causing problems – not necessarily that something is 100 percent perfectly legal,” Bomar wrote in an email.

Evans has described his grandfather immigrating “legally” or “the legal way” on multiple occasions, and as recently as June 24. Bomar declined to respond to questions about that language on the record and denied or ignored repeated requests to interview Evans for this story. After being sent a detailed list of questions about the documents Newsline obtained and Evans’ history of false statements about his grandfather’s immigration history, his representatives stopped responding to inquiries and ignored more than a dozen follow-up messages via phone, text and email.

“I’m more surprised than anything, but also at the same time, it doesn’t really shock me,” says Keilly Leon, north regional organizer for the Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition.

“I think it just goes to show how harmful this rhetoric is – ‘I did it the right way’ versus ‘I did it the wrong way,'” adds Leon, a Greeley resident and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals recipient. “Even folks that immigrated decades ago … experienc(ed) this way that the government has continuously allowed this broken system to separate families and force people to find other ways to come into the country.”

Familiar Anti-Immigrant Attitudes

By Evans’ own reckoning, his family’s story resonated with voters in Colorado’s battleground 8th District, where more than 3 in 10 residents are Mexican-American, helping propel him and other Republicans to victory in a 2024 election defined in large part by immigration and border issues. The 8th District, drawn by an independent redistricting commission in 2021, encompasses Denver’s northern suburbs and parts of rural Weld County.

“My story is the same as so many other stories in the Hispanic community that did it the right way,” he said in a June 24 radio interview. “They took the time and the effort to come here legally, to build a business, to start a family. And then they turn around and they see a bunch of folks rolling across the southern border, literally getting handed out taxpayer money for all of the different things that the Biden administration threw at them.”

Such rhetoric from Evans, Trump and other right-wing politicians did lead to a “fracturing” among Latino voters, says Romeo Guzmán, an assistant professor of history at Claremont Graduate University who studies immigration. But that may be changing fast as Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents begin to carry out the Republican agenda, he adds. A CBS News poll released July 20 showed that support for Trump’s immigration plans has fallen, with a narrow majority of Americans now opposed to his deportation program.

“There’s a kind of tension happening now, with folks who may have voted for Trump thinking they’re somehow different from these unauthorized, quote-unquote ‘illegal’ immigrants,” Guzmán says. “What they’re finding out is that actually, for the Trump administration, for ICE, those differences are not as clear as maybe they imagined.”

Long before his grandson’s repetition of his story on the campaign trail, Cuauhtemoc Chavez belonged to a previous generation of immigrants who faced obstacles and prejudices closely resembling the ones faced by immigrants today.

In the wake of their country’s long and bloody revolution, record numbers of Mexicans entered the U.S. both lawfully and unlawfully during the 1920s. The arrivals fueled a restrictionist campaign that led to the passage of the Undesirable Aliens Act of 1929, which expanded federal deportation powers and, for the first time, made crossing the border without authorization a misdemeanor criminal offense.

Evans’ great-grandmother, Luz Garcia Chavez, crossed into El Paso with her children five months after that law took effect, the INS records show. Without proof of lawful entry, the Chavez family became part of a large population of foreign nationals considered “deportable aliens” under U.S. immigration law.

Anti-immigrant sentiment deepened throughout Cuauhtemoc’s childhood in the 1930s. As the Great Depression set in, immigrants were blamed for taking jobs away from citizens, and for straining state and federal welfare programs. Young Mexican-Americans were vilified first as liquor-smuggling gangsters and then, after Prohibition’s repeal in 1933, as peddlers of marijuana and other drugs. Deportations increased, while as many as 1 million new arrivals and their children, some of them U.S.-born, were pressured into returning to Mexico as part of what became known as the “repatriation” movement.

“There is a lot of coercion that takes place, and a lot of fear tactics,” Guzmán says. “One of the ones that’s really well documented is this big raid of La Placita Olvera in L.A. that is very similar to the sort of raids that we’re seeing now – trying to have a show of force as a way to get people to go back.”

Misrepresentations and Discrepancies

At times, Evans’ statements about his grandfather have contained clear misrepresentations, such as a June 24, 2024, Facebook post stating that Cuauhtemoc had “immigrated … in search of a safer place to raise a family.” A day later, Jennifer Chavez, Cuauhtemoc’s daughter and Evans’ aunt, replied to his post.

“When your grandfather immigrated from Mexico, he was 5 years old,” Jennifer wrote. “Don’t be misleading.”

In a 2022 statement to Spanish-language newspaper La Prensa de Colorado, Evans, then a first-time Statehouse candidate, wrote that Cuauhtemoc had “acquir(ed) citizenship in 1943,” while serving in the Army. In fact, records show that he did not apply for naturalization until several years later, in 1946. The discrepancy is significant because Cuauhtemoc’s naturalization petition indicates that he was granted citizenship under a 1944 law that eliminated proof of “lawful entry” as a requirement for naturalization.

Evans repeated the inaccurate timeline during his 2024 congressional campaign. He told the Berthoud Weekly Surveyor that it “took (Cuauhtemoc) 13 years to get his citizenship,” likening his wait to a story he’d heard on the campaign trail of a Colorado resident who “legally pursue(d) citizenship for 17 years.” But Cuauhtemoc affirmed twice – first on his 1941 AR-2 form and then on his 1946 petition for citizenship – that he had not previously applied for naturalization.

Then-state Rep. Gabe Evans speaks on the floor of the Colorado House of Representatives on Nov. 20, 2023.

Sara Wilson/Colorado Newsline

When contacted by Newsline, Jennifer Chavez said that while she wasn’t shocked by the news that her father’s family entered the country unlawfully – “that was just the way of life back then,” she sid – their undocumented status was not common family knowledge.

“I don’t think anyone in the family has ever seen any of that,” Jennifer said of the INS forms Newsline obtained.

Like many American families, the present-day Chavezes are divided by politics, and Evans’ repeated invocation of Cuauhtemoc ​​to defend Republican policies drove the wedge further. Jennifer, who said she last saw Evans in person at a wedding in 2020, wrote an op-ed last year opposing his congressional candidacy. In an interview, she said her father and her nephew were on opposite sides of an estrangement in the family stretching back decades.

“Gabe, in reality, barely knew my dad,” she said. “They just didn’t see each other very often. My sister (Evans’ mother) just didn’t click with the family anymore. … He’s trying to cultivate the Latino heritage thing, but he really didn’t know my father, because he rarely saw him.”

Evans’ representatives didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment on Jennifer’s characterization of his relationship with his grandfather.

“For Gabe to portray my dad as being in support of someone like Trump would have gone over like a lead balloon,” Jennifer added. “He really misrepresented who my father was.”

When asked about another line from Evans’ campaign announcement email – in which he said that his mother, Rebecca Chavez, “thought she would spend her whole life in a one-room hut with a dirt floor in Juarez, Mexico” – Jennifer Chavez burst out laughing.

“We were raised in a middle-class neighborhood in El Paso,” she said. “We went to Eastwood High School, which was predominantly Caucasian. … To this day, none of us are fluent in Spanish.”

“You Need to Go Back”

During the 2024 campaign, Evans, though reluctant to answer the question directly, repeatedly affirmed his support for Trump’s plans to deport all of the estimated 12 million people living in the country without permanent legal status.

“​​If you are not lawfully here, you need to go back,” he said when pressed on whether he supported Trump’s “deport them all” agenda during a June 2024 primary debate. “Yeah, you go back, and you wait in line the way everybody else does in a law-abiding society.”

He softened that stance with his July 15 cosponsorship of the Dignity Act, a bipartisan proposal to provide relief from deportation to some undocumented immigrants.

The proposed relief falls far short of measures that once allowed Evans’ grandfather and other members of the Chavez family to acquire U.S. citizenship. Only those who entered the country prior to 2021 would be eligible for the program. Those who qualify would be required to pay $7,000 in restitution and be barred from accessing federal benefits, and the program would offer legal status but no pathway to citizenship – not even for so-called Dreamers, who, like Evans’ grandfather, were brought to the U.S. as children.

“No amnesty. No handouts. No citizenship,” Evans’ cosponsor, Florida Republican Representative María Salazar, said in a press release announcing the bill.

Demonstrators rally at the Colorado Capitol against the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement policies, on June 10, 2025.

Chase Woodruff/Colorado Newsline

Evans did not respond to questions about whether he supports the DACA program or a pathway to citizenship for anyone currently in the U.S. unlawfully, or why he believes immigrants today should be treated differently than his grandfather’s family was. He did not respond to questions about whether he feels he misled the public about his grandfather’s history and if he plans to change how he talks about it going forward.

Tensions have risen across the country in recent months as ICE agents begin the dramatic operational shift necessary to achieve Trump’s mass-deportation targets. The share of people in ICE detention without a criminal record has risen sharply, according to agency data analyzed by the University of California Berkeley School of Law’s Deportation Data Project. In Colorado, those recently arrested by the agency have included a family with a 1-year-old child attending an immigration court hearing in Denver; a 19-year-old Utah nursing student with no criminal record, detained after a traffic stop near Grand Junction; and prominent immigrant rights advocate Jeanette Vizguerra, a grandmother taken into custody outside her workplace, Target.

Evans has dismissed concerns about expanded ICE activity, accusing critics last week of “vilifying the law enforcement agents working to make our communities safer.” He championed the recent Republican reconciliation bill’s expansion of the agency’s funding, an $80 billion package aimed at quadrupling the scale of its detention and removal operations. He has continued to echo the anti-immigrant rhetoric that targeted young men like his grandfather a century ago, including by spreading false claims about crime rates following an influx of immigrants to Denver, and assailing Colorado’s “sanctuary” policies and a state-run program that offers health coverage to undocumented children.

There’s growing fear about Trump’s crackdown, Leon says, among immigrants in Weld County, a more rural area that lacks the vocal and organized network of advocacy groups that exists in Denver.

“We’re seeing that ICE agents are becoming more unpredictable,” says Leon. “These billions that are being thrown at ICE just harms our communities, it scares our children, who are a huge part of the Greeley community.”

“The idea that a group of people do it ‘the legal way’ or ‘the right way’ – the reality is that those categories have been slipperier and much more confused than we imagine,” Guzmán says. “Because ‘the right way’ is historically contingent on the laws that are impeding your movement.”

Soon after his inauguration, Trump launched an effort to end the centuries-old legal bedrock of birthright citizenship, a move Evans has refused to take a position on. In recent weeks, the president has threatened to “denaturalize” many legal immigrants, including New York City mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani and other political opponents. Millions of people who entered the country over the last five years did so as lawful asylum seekers or under humanitarian parole designations like the temporary protected status program – legal avenues the Trump administration has moved aggressively to shut down.

“If you’re a refugee, what does ‘the right way’ mean?” Guzmán adds. “It means you show up to the border and claim refugee status.”

“This is not a diss on anybody; people are not historians,” says Guzmán. “The problem, of course, is when people start claiming that their family did it one way, (and say) ‘why can’t you do it that way?’ – usually that’s code for both a lack of knowledge of their own family history but the larger ways in which immigration history has functioned for us.”

Chase Woodruff, a former Westword staffer, is a senior reporter for Colorado Newsline, part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Follow Colorado Newsline here.