LightFieldStudios/iStock

Audio By Carbonatix

Even after eight years of litigation, bills passed by the Colorado Legislature, and countless frustrated and grieving family members, hundreds of people with severe mental illnesses still sit in Colorado jails for months before being convicted of a crime.

They’re waiting for evaluations or services to ensure that they’re competent to stand trial, a concept that’s supposed to protect people with disabilities or behavioral health disorders from having to defend themselves against charges they may not have the capacity to understand. But the State of Colorado has been unable to resolve a massive backlog in the system, which keeps people waiting long past the deadlines established by law.

Janet Van der Laak’s son, Matt, is one of those people. He’s been found incompetent several times after minor criminal charges, and over the past five years, she has gone through more than her fair share of calling jails and mental hospitals to find out where he is and if she can talk to him.

She’s hoping that a new pilot program administered by the Mental Health Center of Denver, one of the city’s biggest community behavioral health care providers, will change that. Matt (van der Laak requested that Westword use only his first name to protect his privacy) is currently facing several minor criminal charges – misdemeanors for park curfew violation, trespassing and giving false information, as well as a low-level felony for drug possession.

Van der Laak feared he would again be shuffled from jails to the state hospital and back, caught up in what advocates say is a broken system with a massive backlog. But on Thursday, November 21, a judge approved Matt to be the first participant of the Mental Health Center of Denver’s new program, called Community Based Enhanced Restoration. He’ll be released from jail to live with his family and get access to mental health services on a consistent basis. The goal is that he’ll eventually be “restored” to competency to face his charges in court, without having to wait in jails and hospitals for months before doing so.

If a judge, lawyer, police officer or anyone involved in a case suspects that a defendant cannot understand the court system, their charges or their basic legal rights, they can raise the issue of competency. The judge then orders a competency evaluation, which is performed by trained psychiatrists or psychologists, either in a jail or at the Colorado Mental Health Institute at Pueblo, a state-run hospital. Because there are only a limited number of evaluators and resources to conduct evaluations, people have to wait for weeks just to get evaluated – often in jail, unless they have been bonded out. The state can legally only hold someone for up to 21 days before they receive a competency evaluation in the Pueblo hospital, and 28 days if they receive the evaluation in jail.

Those found incompetent to stand trial are referred to a competency restoration program. The goal of competency restoration is far from “restoring” the patient to health. It’s designed to educate patients about their basic legal rights so that they can pass the competency examination and face criminal charges. If someone is severely mentally ill, this can take months; during that time, they may be medicated, but they don’t always receive a full array of mental health treatment services. Historically, the only options for restoration have been an inpatient program at the Mental Health Institute in Pueblo, where court-ordered demand for competency restoration nearly always exceeds the 455-bed capacity. The Arapahoe County Jail also runs a jail-based competency restoration program called RISE, which has 94 beds.

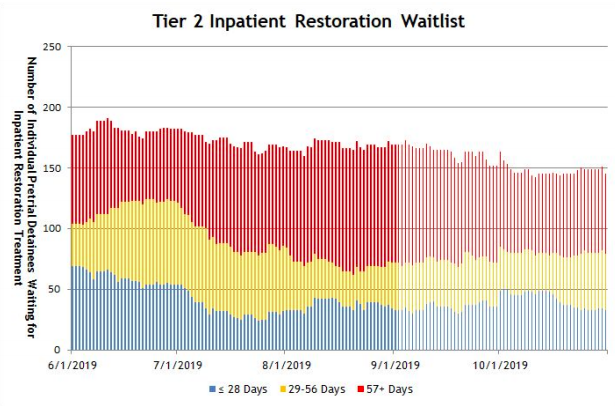

Because of the limited capacity of these programs, there is always a massive backlog. After a person is found incompetent, the state has 56 days to offer them a place in a competency restoration program (or seven days if evaluators determine the person is a danger to themselves or others). The state must pay fines for every day it holds people in jails over these limits.

The wait time for restoration treatment at the state hospital can still be months, despite increased efforts to address the issue.

Colorado Department of Behavioral Health

Alison Butler, the director of legal services at Disability Law Colorado, sued the Colorado Department of Human Services in 2011 over delayed competency evaluations, a case that was settled in 2016 but subsequently reopened after the state still failed to comply with the required time limits that people should spend in jail. After a second settlement, Governor Jared Polis signed two new mental health bills that direct a subcommittee of the state’s Behavioral Health Task Force (a committee of stakeholders working on a plan to reform Colorado’s fractured behavioral health care system) to help the state’s Department of Human Services develop a comprehensive plan for the state to better meet those deadlines. According to the department’s data from October, people waited an average of 83 days in jail before getting into competency restoration.

Butler argues that the competency system has become a “revolving door” that keeps mentally ill individuals in prison. When mentally ill people spend months in jail for a minor infraction, then are released into the community without having received treatment, they are likely to end up back in jail and continue the cycle.

The impacts can be severe. On November 3, a woman named Jillian White died by suicide while detained in the Pitkin County Jail shortly after being found incompetent. Her lawyer said White was waiting for a bed at the state hospital.

“Most of these people don’t need to be in jail,” Butler says.

She argues that for most patients who don’t require extensive supervision for their own safety, there’s no need for competency restoration to be done in a confined hospital. “We need to treat [mental illness] as a medical condition and provide support,” she explains. “Nobody is claiming that when you have uncontrolled diabetes you need to go to jail to get your medication. Everyone recognizes that there is a way to treat that in the community.”

The Mental Health Center of Denver hopes Community Based Enhanced Restoration will provide just the kind of treatment that Butler has been pushing for. According to Carleigh Sailon, the clinical supervisor of the program, clients will be able to live independently or with family members, and case managers will see them at least three times a week to help connect them and transport them to services from Mental Health Center of Denver and other providers, including benefits, employment, education, psychiatry and medication management. The Center will also help create a housing plan for those who don’t have family or financial support.

The program will stay small for now, capped at thirty clients. “The hope is that if it’s successful we would replicate it elsewhere,” Sailon says. “Getting people back to their community is incredibly important. Being in custody is isolating and traumatizing, especially for people with a severe and persistent mental illness. So returning them to the community, we hope, is a more conducive environment to recovery.”

There are challenges to getting outpatient restoration programs like the Mental Health Center of Denver’s off the ground. “In order to make these programs in the community financially feasible, they need to have people in them to bill for, but they’re not going to be able to have people until they have a good track record and judges feel comfortable referring them,” Butler explains.

Matt was diagnosed with chronic paranoid schizophrenia in his early twenties. The now-27-year-old has a “childlike demeanor,” van der Laak says. He’s “kind, loving and very docile.”

He’s never been violent or combative, she says, but he is prone to wandering and behaving oddly in public, especially when he’s off his medication. He once entered a stranger’s house, and police found him cowering in the corner. Most recently, police arrested him after they found him on the 16th Street Mall, crawling and rolling on the ground. He was off his medication, and had self-medicated with illicit substances, van der Laak says.

“I have a hard time understanding why police would even arrest someone like that,” she explains.

Spending so much time in jail has affected how Matt perceives himself. “He called me [from jail] a couple weeks ago,” van der Laak says. “He said, ‘Mama, when can I come home?’ He goes, ‘I won’t be bad.’ In his mind he thinks he’s done something bad.”

She’s hoping that his charges are eventually dropped and that the program will actually get Matt some of the mental health treatment he needs.

“This program is a godsend, because it gets him out of jail,” van der Laak adds. “I am super-excited for this, because I don’t want him in [the state hospital in] Pueblo. Pueblo, to me, is another jail.”