Colorado Department of Corrections

Audio By Carbonatix

Colorado has paid $1.1 million to settle a lawsuit brought by a state prisoner who was stalked, assaulted and almost killed by gang members over a period of years while prison officials rejected his numerous pleas for protection.

The settlement contains no admission of wrongdoing by the Colorado Department of Corrections. But the allegations detailed in John Snorsky’s lawsuit raise questions about the agency’s willingness and ability to protect its most vulnerable inmates – including key witnesses in prison murder investigations – from the long reach of prison gangs. According to Snorsky, CDOC officials not only ignored documented threats against him, but deliberately put him in harm’s way by housing him with known associates of a white supremacist who wanted to kill him.

“This is a common practice,” Snorsky tells Westword. “They’ll house you with your worst enemy, and when you’re attacked, they [act like they] did nothing wrong.”

No Way Out

Snorsky, 37, is serving a thirty-year sentence for a case that made headlines back in 2013, when he abducted an eight-year-old girl from an Aurora home he was burglarizing. Snorsky pleaded guilty to first-degree burglary and second-degree kidnapping but insisted he was “tripping on acid” at the time and had released the girl moments later outside her residence. The judge who sentenced him called him “the boogie man” and “the bump in the night.”

Although he was not charged with a sex offense, Snorsky soon encountered trouble behind bars from inmates who assumed that the high-profile abduction was the work of a child molester, or “chomo,” the lowest caste in the prison pecking order. He was beaten severely by three prisoners while in jail in Adams County and made a court appearance in a wheelchair. After his arrival in CDOC, he began carrying a shank to defend himself from other assaults, which led to disciplinary write-ups and placement in solitary confinement in the system’s supermax, the Colorado State Penitentiary.

In 2015, a new occupant moved into the cell next to Snorsky’s: Chad Merrill, a high-ranking member of the 211 Crew, the white supremacist gang linked to the 2013 murder of CDOC director Tom Clements. According to court records, Merrill is serving a life sentence for gang-related crimes outside of prison but has also been the subject of multiple criminal investigations within the prison system. “He is the most evil, dangerous, and violent individual I have come across in my decades in law enforcement and corrections,” a veteran officer and gang expert declared in one report.

Soon after his arrival at CSP, Merrill began bragging to Snorsky about “that chomo that I killed” at the Limon prison. Snorsky was skeptical at first, but Merrill provided graphic details of strangling his cellmate from behind and then slashing at his neck until the man was almost decapitated. As Merrill yammered on about how much he hated chomos, Snorsky realized that the victim was a friend of his – Joshua Edmonds, serving a fifteen-year sentence for burglary. When Snorsky pointed out that Edmonds wasn’t a sex offender, Merrill replied, “I kinda fucking feel bad now.”

Chad Merrill was described by one veteran officer as “the most evil, dangerous and violent individual” he’d encountered in his career.

Colorado Department of Corrections

Snorsky relayed what Merrill told him to prison officials. He declared that he was willing to testify against the man who killed his friend if he could be protected. But no move to a protective custody unit was forthcoming – not even after other inmates learned that Snorsky’s name was on a list of witnesses for the prosecution in the homicide case against Merrill. Not even when CSP intelligence officers discovered a hit list drafted by members of another prison gang, the North Side Mafia, that had a star next to Snorsky’s name and the word “rat.”

Not even after Snorsky had been attacked repeatedly, stabbed and beaten and bombarded with feces, and reclassified as facing a “high/impending” threat to his safety. “Every time he is escorted to an area, the other inmates start threatening him,” one officer reported.

Despite mounting evidence that he’d been targeted, Snorsky’s frantic pleas to be placed in protective custody were denied for months. He rarely left his cell at CSP for recreation or anything else.

On February 22, 2017, he was attacked by three inmates and stabbed 43 times, resulting in a collapsed lung and other serious injuries that required hospitalization. His attackers – members of three different prison gangs – were charged with attempted murder.

After that incident, Snorsky was shuttled to different protective custody units, but safety proved elusive. At the Arkansas Valley prison, he was attacked while in protective custody by a gang member who yelled out “Blood!” during the assault. He was also harassed and threatened while in the Buena Vista PC unit, situated in a cramped hallway and featuring a mix of inmates regarded by staff as “cry-babies” and problem cases. (A 2022 report by civil rights attorneys at the University of Denver described the Buena Vista PC unit as “a bleak and dangerous environment,” where “physical violence is rampant and largely unaddressed.”)

Back to Supermax

In 2021 Snorsky was abruptly bounced from Buena Vista and sent back to the supermax, where he was once again in close proximity to the men who had previously tried to kill him. The ostensible reason for the move was that Snorsky “attempted to incite a riot” at Buena Vista, but Snorsky contended that the charge was unwarranted and retaliatory.

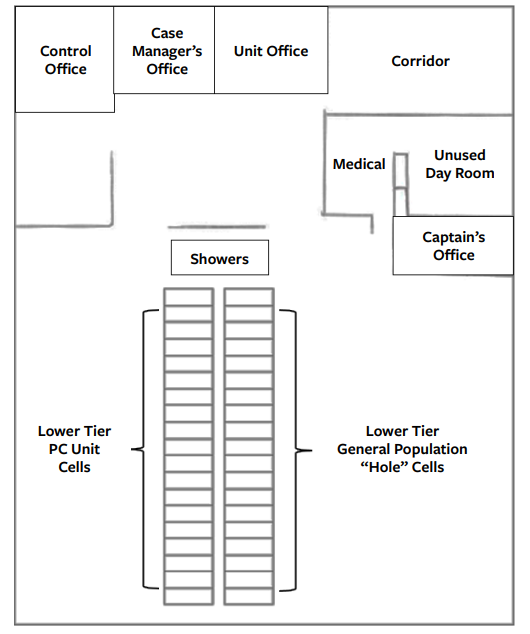

A diagram of the Buena Vista protective custody unit.

University of Denver

Federal magistrate judge Kristen Mix agreed, blasting the CDOC’s “lack of responsiveness and malfeasance” in its duty to protect Snorsky. In 2022 Mix granted a highly unusual injunction that required prison authorities to put Snorsky back in protective custody.

Merrill wasn’t idle during Snorsky’s legal battles. He received his own transfer out of CSP to general population at Buena Vista, where he and two other 211 Crew members killed inmate Matthew Massaro in 2018, crushing his skull in front of cameras and other inmates. Merrill has since pleaded guilty in both the Edmonds and Massaro murders. He is no longer listed in the publicly available CDOC inmate database, possibly because of a move to another prison system under an interstate compact, which allows corrections agencies to “trade” inmates who are considered high-profile or difficult to manage.

The attorneys representing Snorsky did not respond to requests for comment on the settlement of his lawsuit. A CDOC spokesperson provided a general statement declaring that the agency is “committed to protecting those in our facilities” and that requests for protective custody “are handled expeditiously.” But the spokesperson declined to discuss the settlement or answer specific questions about PC practices and Snorsky’s claims of retaliation.

The CDOC is now on its third executive director since Snorsky’s lawsuit was filed six years ago. Snorsky says little has improved for prisoners who defy the gangs and agree to testify against them; he is currently housed in protective custody at the Sterling Correctional Facility and claims PC inmates there have fewer privileges than they did at Buena Vista or Arkansas Valley.

“PC inmates are held in the Level Five part of Sterling, where solitary confinement and death row were housed,” he reports. “We have been stripped of everything, from going to the library, having religious services, any and all mental health, and rehabilitative programs required by parole in order to be paroled. Pretty much, PC inmates are locked in the solitary confinement units, and it’s worse than ever. [Prison officials] worked to create the most miserable environment for PC, to force inmates out of PC and undermine all litigation and progress made. … It’s not looking good.”

The $1.1 million settlement is one of the largest ever awarded to a Colorado inmate. Snorsky says he recently received the payment, but spending it may require some patience – and luck. He is not eligible for parole until 2034.