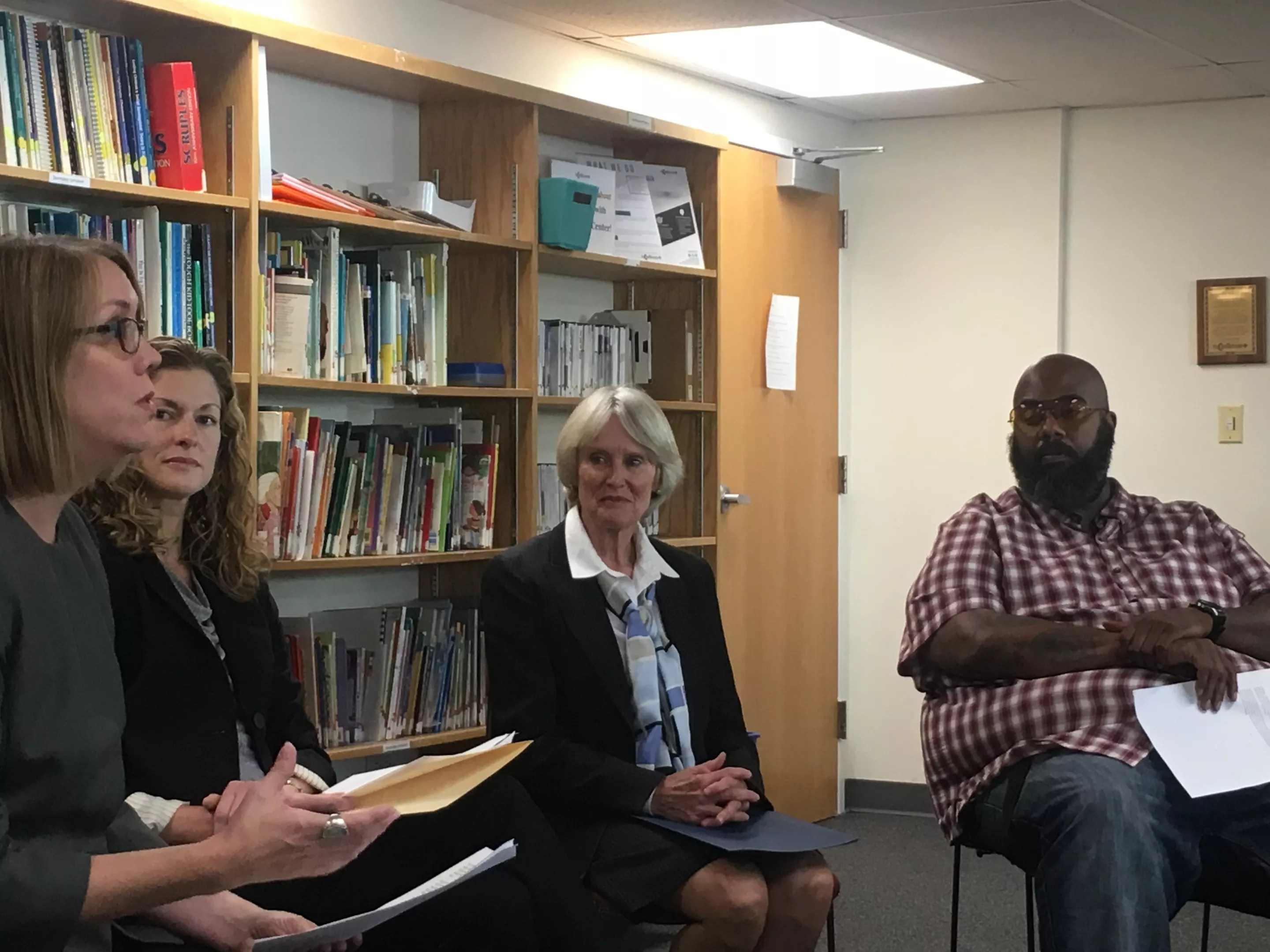

Sara Fleming

Audio By Carbonatix

This summer, Jason McBride was driving east on Colfax Avenue with a group of kids he mentors when he unexpectedly found himself in the middle of a street-side standoff that ended in a young man running into him at 30 miles per hour and driving away.

McBride had been sitting behind the man and another truck at a traffic light. When the man didn’t move after the light turned green, McBride honked repeatedly. The young man walked over to his car and started cussing him out; McBride shot back a few words of his own, and the conflict escalated. When both of them turned the corner onto Franklin Street and got out of their vehicles, the man pulled out a tire jack, tried to hit McBride car, and eventually pulled a hit-and-run.

Even after police arrested the man, McBride wasn’t at ease with what had happened. “I pushed some buttons that maybe I shouldn’t have that day, you know – people do have to be responsible for their actions. But if I could take any of those things back, maybe it wouldn’t have happened,” he says. That hit hard when he saw the video of what led up to the incident. “What I didn’t know is that a homeless person was walking across the street and fell, and their stuff was all over the street, and he was helping him gather the stuff. I really felt like a jerk…he was really trying to do something good, and I kind of ruined that for him,” McBride says.

As a mentor for the grassroots organization GRASP, which works with at-risk youth and active gang members to push against cycles of violence, McBride says he did not want to see a young man with kids go to jail. He wanted to model the ownership of responsibility it takes to prevent that outcome. “I told [the prosecutor],” McBride continues, “if there’s a way, I would just like to talk to this kid and just see what he’s thinking.”

As it turns out, there was a way. McBride was able to go through a pilot version of a new program launched by the Denver District Attorney’s Office today, September 12, called Restorative Denver. During a three-hour conference with the offender, McBride was able to apologize for his own actions and “find out what was on his mind as we were going through our situation.” As a result of their conversation, the offender’s charges were dropped, and instead he agreed to serve his community through a series of steps that McBride had suggested.

Restorative Denver is an alternative to the traditional court system that bypasses the typical adversarial lawyering and quest for due punishment, instead giving the victim and the offender a chance to talk things out directly. It’s the first pre-trial restorative justice program for adults in the city.

“It’s a process to allow more healing, and it’s kind of a different way to look at criminal justice and what’s an appropriate resolution,” District Attorney Beth McCann said at a press conference announcing the program.

“No one talks to anyone,” McCann says of the criminal justice system she is rooted in as a former prosecutor. “So as a good defense attorney, you’re going to tell your client, ‘You can’t talk to anyone, don’t talk to the victims, don’t even send them a letter of apology.’ Because they don’t want anything that can then be used against them…so I think its frustrating, for the victims in particular, because they don’t have an opportunity to hear what actually was going on, and why defendants don’t have an opportunity to apologize to someone and understand the impact that their actions have caused.”

Restorative justice is a concept that echoes practices of indigenous communities around the world, but according to the International Institute of Restorative Practices, it originated in its modern form in Ontario, Canada, in the 1970s and has since been slowly gaining popularity. Today, it’s mainly practiced in some parts of the U.S. as an optional extralegal process. The practical forms and philosophy behind different threads of restorative justice vary, but the general outlook is that instead of punishing the offender, the victim and the offender will work together to repair the harm done.

“Ultimately, restorative justice focuses not on punishment, but on making things right and on reintegrating the person who caused harm back into the community with the skills to make better choices in the future,” explains Beth Yohe, executive director of the Conflict Center, a community nonprofit in Sunnyside that will be partnering with the DA’s office to facilitate the program.

Restorative Denver will take referrals from prosecutors in misdemeanor cases in county court. The victim must consent to the restorative process – though victims can choose a surrogate to represent them instead of participating directly – and the defendant must admit guilt and be willing to repair the damage done.

Before meeting face to face, both parties will go through pre-conference preparation in which they learn about the process and come up with possible outcomes specific to their situation. Then, together with two facilitators, other supporters and community members (who may be members of a community affected by the crime or people trained by the Conflict Center), they meet in one two- to three-hour conference, the end product of which is an agreement that outlines steps that the offender will take to repair the harm.

Those outcomes are flexible. It could be that someone who damaged physical property helps repair it. Or it could be a decision that requires the offender to give back to the community by volunteering. As long as the offender follows through with the agreement, the case will be dismissed and the charges dropped.

McCann created a juvenile restorative justice program when she took office in 2017. Initially, she says, she was skeptical of the idea, but then she observed a circle in action. “At the end they were all hugging each other. I thought, this works. It’s empowering – for victims of crime, and also…for the community to have this opportunity to discuss it.”

The program has facilitated 24 juvenile restorative justice conferences in two years. McCann’s office has been working throughout the summer to develop the program for adults, looking to similar initiatives in Longmont, Colorado Springs and Estes Park, among other cities, as models. Felony cases like McBride’s won’t be eligible for referral to Restorative Denver, at least in this initial phase; nor will cases of sexual assault, domestic violence, or misdemeanors that don’t have a defined victim, such as drug offenses. McCann says her office wants to start with less high-risk cases to see how the program goes, but adds that she is not “closing the door on anything.”

Sharletta Evans, whose three-year-old son was murdered in a drive-by shooting in 1995, has already seen the benefits of restorative justice in Colorado. “I needed closure, and I wanted to participate in my healing as well as looking at those who are incarcerated, that have been affected by committing such a heinous crime.” She pushed for restorative justice legislation on a state level. Eventually, through the Colorado Department of Corrections’ victim-offender dialogue program, she was able to meet face to face with the perpetrator and later his accomplice, who had both been sentenced to life without parole. She couldn’t change their sentences, but, she says, “It was a profound change…we were unpacking the whole time, and he’s expressing his remorse, and all the things he’s experienced, and why he did it.” She believes “it gave him closure, it rid him of guilt, shame, and the burden of what he’s done.”

For her own part, she says, “I was reconciled back to myself. I began to be able to live again…I could think about my son in a more pleasant way, his three years of living, and the things that we used to enjoy.”