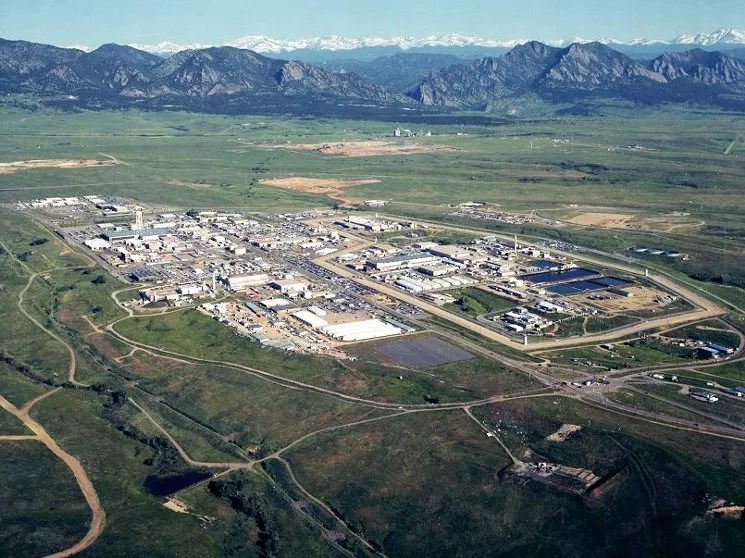

DOE

Audio By Carbonatix

Colorado almost had its own Chernobyl.

That’s what then-congressman Jared Polis told the U.S. House of Representatives on May 12, 2009, the fortieth anniversary of a fire at what was then called the Rocky Flats National Munitions Plant, sixteen miles upwind of Denver.

“I rise today to commemorate one of the most fateful days in the history of the State of Colorado, the day the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant outside of Boulder nearly became America’s own Chernobyl, some thirty years before that terrible accident in the Ukraine,” Polis told his colleagues. “On Mother’s Day of that year, a fire broke out amid the glove boxes in Building 776, where plutonium spheres were being manufactured for use as cores for some of the most powerful weapons in human history. The fire quickly spread throughout the facility, as many of the fire alarms had been removed to make room for more production. It is estimated that between 0.14 and 0.9 grams of plutonium 239 and 240 were released before a heroic band of perhaps forty firefighters were able to control and eventually douse the fire. Those firefighters faced the immense decision of whether to battle the blaze with water, which could have set off a chain reaction, with the resulting explosion literally contaminating the entire Denver metropolitan area. Luckily for us all, they chose correctly.

“Still, plutonium was released into the environment from that accident, through the air vents in the roof of the building and via firefighters extinguishing it. Thousands of Coloradans were exposed, although how many we’ll never know. The firefighters, of course, were exposed most severely, and everyone nearby faced greatly increased risks of serious disease. Indeed, many of those involved have since contracted and died from cancers and other conditions tied to radiation exposure.”

HBO’s Chernobyl brought that disaster back into the public consciousness this summer.

HBO

Unlike Chernobyl, the site of a massive nuclear explosion on April 26, 1986, that exposed at least half a million Russians to radiation, decimated the land for miles around and inspired HBO’s Chernobyl that educated a new generation to collateral damages of the nuclear age, Rocky Flats was not a nuclear power plant. In fact, Colorado’s only nuclear-generating facility, Fort St. Vrain near Platteville, had its own problems from when it began generating electricity in 1976 and was shut down entirely in 1989.

By then, what became known as the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant had been in operation for almost three decades; it was a manufacturing facility that created plutonium triggers for this country’s nuclear arsenal. But it still dealt with one of the most toxic elements on the planet, one with a half-life of 24,000 years, as well as many deadly chemicals. By the time of the 1969 Rocky Flats fire, the plant had been manufacturing those triggers for sixteen years, largely in secret.

Rocky Flats was not Chernobyl. But what happened there was bad enough – though just how bad may never be known. Documents about the plant, like some of the plutonium that was processed there, have a way of disappearing.

PROJECT APPLE

“Good News Today,” the Rocky Mountain News trumpeted on March 23, 1951, when the Atomic Energy Commission (now the Department of Energy) announced that it had chosen a site near Denver for a $45 million federal facility that had gone by the code name Project Apple. The 6,500-acre-plus spot was on a high plateau near the foothills, with stunning views, some ranching, creeks running through the land, and not much else. The announcement didn’t get into many details – the site-location team had warned the AEC that there might be an “undesirable reaction of the public” if it learned of the project’s secret mission – but it was bringing jobs to the area, and those jobs paid well. It wasn’t until June 1957 that the Denver Post dropped the bombshell that handling plutonium was a routine part of the job, a detail shared by the plant after two employees were injured in an explosion and fire at the facility; they’d been handling radioactive materials in building 771. Three months later, there was another fire at the plant, when filters over the glove boxes designed to keep plutonium from escaping caught fire. Firefighters turned on the ventilation fans, which spread the flames; seven days later, monitors showed that smokestack emissions still contained levels of radioactive elements 16,000 times greater than the standards of the day.

Inside one of the rooms at the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant.

Rocky Flats Cold War Museum

By then, scientists had realized that they’d misread the wind patterns when siting Rocky Flats; they’d relied on measurements taken at Stapleton Airport northeast of Denver, without accounting for how winds shifted as they came over the mountains and through the canyons. Rather than being safely out of the path of any plutonium release, Denver was at ground zero, sixteen miles downwind. Even so, residents were not warned of potential dangers after the fires.

Then came another fire, in 1969, which again started in glove boxes in buildings 775 and 776; it triggered the costliest industrial accident in the United States up until that time. Firefighters managed to contain the fire, and the government and plant operator Dow Chemical contained the fallout from more revelations of the work being done at Rocky Flats.

But word did slowly leak out. In 1975, the year that Rockwell International took over operations at Rocky Flats, nearby landowners sued the government for contamination problems they were finding on their property. Workers at the plant were also complaining about significant health problems. And demonstrators regularly gathered outside the gates, though they were usually protesting against nuclear weapons in general, not the environmental problems that the manufacturing of those weapons might create.

Joe Daniels collected his photographs of the ’70s protests in a book.

“A Year of Disobedience”

By 1978, Rocky Flats was regularly exploding in the headlines as those demonstrations grew larger. That fall, Daniel Ellsberg – yes, the Daniel Ellsberg of Pentagon Papers fame – went on trial in Jefferson County, along with nine other members of a group that had been accused of trespassing and obstruction outside the plant seven months earlier. Using Colorado’s choice-of-evils statute, which suggested they could break the law if they were pushing for a greater public good, the defendants decided to put Rocky Flats itself on trial, arguing that it was a public health hazard to nearby residents and also threatened world security by increasing nuclear stockpiles. But on November 20, 1978, Judge Kim Goldberger ruled that the defendants could not use the choice-of-evils defense. While the dangers at Rocky Flats were “real and continuing,” the judge said, “the courts may not be used as political or legislative forums.” After an eleven-day trial, the protesters were found guilty.

At the time, Dr. Carl Johnson, head of the Jefferson County health department, was revealing his own concerns about the evils of Rocky Flats. He released studies suggesting that Denver’s overall cancer rates were higher than expected, and the rates around Rocky Flats higher still. Property near the plant set for the development of 10,000 homes exceeded the state’s plutonium soil contamination standard by a factor of seven, he reported. As a result, federal housing officials directed realtors to warn prospective homebuyers who wanted government loans in order to purchase houses in the area that there could be potential liabilities.

In 1981, Johnson was fired by Jefferson County. The feds soon removed its directive to realtors.

The protests continued. So did the production of nuclear triggers at Rocky Flats.

SPILLED SECRETS

On June 6, 1989, more than seventy FBI agents raided Rocky Flats, the first-ever raid of one federal agency by another. Led by FBI agent Jon Lipsky, the raid was based on more than two years of investigations inspired by information leaked by whistleblowers, including Jim Stone, an engineer laid off from the plant in 1986 whose case against Rockwell eventually went to the U.S. Supreme Court. Stone had given a 1986 DOE memo to Lipsky noting that some of the hazardous waste treatment facilities at Rocky Flats were “patently illegal,” and that the plant was “in poor condition generally in terms of environmental compliance.” Stone warned that proper permitting measures weren’t being filed, waste was being improperly stored, and some plutonium was even missing. Along with an investigator from the criminal enforcement division of the EPA, Lipsky looked into all of the allegations, then prepared an affidavit that guided the raid. Agents took such a staggering amount of material during their three weeks at the plant that U.S. District Court Judge Sherman Finesilver decided to impanel the state’s first-ever special grand jury to focus on this single case.

In the first week of August 1989, two dozen citizens from across Colorado were sworn in as members of Special Grand Jury 89-2. The grand jurors met for a week every month for over two years, and after hearing from dozens of witnesses and going through hundreds of boxes of documents, they were prepared to consider charges not just for workers at the plant, but for their federal overseers. “We didn’t care who they were or how high up the chain of command they were,” one grand juror later told Westword.

Ultimately, they decided that eight individuals should be indicted for environmental crimes – five from Rockwell and three from the DOE. But in November 1991, then-U.S. Attorney for Colorado Mike Norton told the jurors that he wouldn’t sign any indictment naming a DOE or Rockwell employee. A month later, prosecutors told the grand jurors that they were done presenting evidence, and that the grand jury’s work was essentially over.

Wes McKinley was the foreman of the Rocky Flats grand jury.

colorado.gov

On December 30, 1991, grand jury foreman Wes McKinley, a rancher from the very southeastern corner of Colorado, sent a note to Finesilver’s clerk, asking for a final session so that the grand jurors could do their duty, fulfilling the obligation that Finesilver had charged them with more than two years before, “to look out for the best interests of the people of Colorado and the national interest.”

That winter, the grand jurors had one last official meeting in Denver, when they drafted three documents: an indictment charging DOE and Rockwell officials with specific crimes (the document Norton had said he wouldn’t sign); a “presentiment” outlining the proposed indictments, which they hoped Finesilver would release even if the indictment itself never saw the light of day; and a report outlining their investigation and their findings of non-criminal conduct that they felt the public had a right to know. Nineteen of the grand jurors gathered to sign these documents, which they placed in a vault. And then they were sent home, with reminders that all grand jury work is done in secrecy; if they broke confidentiality, they could be charged with contempt of court, fined and even jailed.

There was hot stuff in that report, including this: “The Department of Energy, its contractors – Rockwell International, Inc., EG&G, Inc. – and many of their respective employees have engaged in an on-going criminal enterprise at the Rocky Flats Plant, which has violated federal environmental laws. This criminal enterprise continues to operate today…and it promises to continue operating into the future unless our government, its contractors and their respective employees are made subject to the law… .”

Instead, in March 1992, Norton announced a deal with Rockwell, in which the company pleaded guilty to assorted environmental crimes and was fined $18.5 million. Norton noted that it was the largest fine ever collected by the federal government for violations of hazardous waste disposal laws, but it was about $3.8 million less than the bonuses Rockwell had been paid to operate the plant during the time it was, by its own admission, knowingly breaking those laws. No individuals were named in the settlement. In fact, the deal assured that none would be charged later, and the company was protected from future legal fees.

That June, Finesilver signed off on the settlement after rejecting a request to release the report the grand jury had written. But the grand jurors concerns didn’t stay secret. The result was Bryan Abas’s “The Secret Story of the Rocky Flats Grand Jury,” published September 30, 1992, in Westword.

It wasn’t Chernobyl, but the story about Rocky Flats exploded just the same.

CLEANING UP

After the raid, Rocky Flats never made another nuclear trigger. The feds and Rockwell agreed to an early termination of the Rockwell management contract in September 1989, the day after the company filed a civil suit against the DOE, the EPA and the Department of Justice, arguing that the feds had failed to provide proper waste-disposal sites for radioactive materials. A week later, Rocky Flats was named a Superfund site, and EG&G signed a contract to operate the facility starting January 1, 1990.

By then, the focus had been changed from nuclear-materials production to cleanup, and most of the 5,000-plus employees stayed on to do the job. Among other things, nearly 3,600 containers of pondcrete and saltcrete – 4.3 million pounds of low-level solidified waste that had been packaged like barrels, until they started to crumble and leak (the grand jurors had heard considerable testimony about that failed system) – were moved, and the solar ponds where waste had been stored were drained. Plutonium located in the ducts, which Stone had warned about, was removed.

As the story of the Rocky Flats grand jury became national news, Congress held hearings to determine whether justice had been denied. The hearings made headlines, but secured nothing more than a promise of more transparency from the DOE. Foreman McKinley even ran for Congress, in hopes that he’d be able to tell the full story from the floor of the House of Representatives. (Although that attempt failed, he ultimately served in the Colorado Legislature and co-authored a book titled The Ambushed Grand Jury…and thus far has avoided any contempt-of-court charges.)

In 1995, EG&G staff and the DOE held a Rocky Flats Summit with 150 community activists, regulators, state officials and members of citizen oversight committees to discuss cleanup plans, including reducing the risk of plutonium to site workers and the public, and deferring some environmental restoration and cleanup in order to reduce that risk. When EG&G declined to sign up for a second round, Kaiser-Hill took over the project. The draft Rocky Flats Vision and Rocky Flats Cleanup Agreement were released in March 1996, four years after the Justice Department had made its deal with Rockwell; Governor Roy Romer signed them that June. What had been predicted to be a cleanup project that would take decades and tens of billions of dollars was put on the fast track.

After nearly ten years and $7.7 billion, the remediation job was declared complete in 2005. More than 800 structures had been decontaminated and demolished, including five major plutonium facilities and two major uranium facilities. While much of the low-level radioactive waste was shipped to other disposal sites, the most contaminated rubble was buried far below the ground in the Central Operable Unit: 1,308 acres at the center of the facility, where most of the manufacturing had been done, which would be declared off-limits forever. The 5,000-plus acres around the COU, in the Peripheral Operable Unit, were turned over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2007 to revamp into a wildlife refuge, much as the Rocky Mountain Arsenal had been two decades earlier.

Even though the grand jurors were still silenced, the secrets of Rocky Flats seeped out in other ways. Workers who’d become sick sued the government, and public officials took up their cause. Nearby homeowners who’d suffered bad health and other losses filed a class-action suit against Rockwell and Dow; their case was finally heard in U.S. District Court Judge John Kane’s courtroom, where former FBI agent Lipsky testified as to what he’d found at the plant. Despite the testimony about problems on those properties, houses were popping up along the southern border of Rocky Flats, and some new homeowners started to wonder if they’d bought more than they bargained for. And as plans to finally complete the northwest segment of the beltway around Denver progressed, municipalities began questioning whether construction of the Jefferson Parkway, set to go along the east side of Rocky Flats, would really be safe.

In the Colorado Legislature, Wes McKinley argued for warning signage at the entrance to Rocky Flats. He didn’t get it.

Westword

As the date of the Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge‘s opening neared, activist groups filed suit to keep the gates closed. Last September, Congressman Polis made a last-second request to Ryan Zinke, then-secretary of the Department of the Interior, which oversees Fish and Wildlife, to consider “my constituents’ request that the DOI complete further testing of air, water, and soil at the Refuge site by March 2019, and that until further testing has been completed, the Refuge site remain unopened to the public.”

Although Polis never heard from Zinke, he got his answer: The refuge opened to the public on September 15, 2018 (the suits filed to prevent its opening are still pending). But even those who have no concerns about the refuge’s safety were taken aback last November when a British company proposed fracking alongside Rocky Flats: While cleanup experts had considered the effects of water runoff, and burrowing animals, and even prairie fires, they’d never considered that drilling operations would bore down and then up into the property from the sides. The proposal was pulled, and last month Representative Joe Neguse, who took over the second congressional seat when Polis was elected governor, introduced legislation that would prohibit oil, gas and mineral drilling beneath federally owned Superfund sites, such as Rocky Flats.

Meanwhile, the debate over whether the surface is really safe continues.

In January, attorney Pat Mellen decided to try a different tack. On behalf of seven groups – the Alliance of Nuclear Workers Advocacy Groups, Rocky Flats Downwinders, Candelas Glows/Rocky Flats Glows, Environmental Information Network, Rocky Flats Neighborhood Association, Rocky Flats Right to Know and the Rocky Mountain Peace and Justice Center – she filed a motion asking that materials considered by Colorado’s first-ever special grand jury be released. “The documents gathered by the Grand Jury and now under seal are a unique resource that provides the detailed evidence of whether specific locations or hot spots of unremediated or undiscovered hazardous substances must outweigh a site-wide ‘safe’ determination made for other purposes,” she argued.

MISSING IN ACTION

And then on July 24, Mellen received an email from Kyle Brenton, assistant U.S. Attorney in the U.S. Attorney’s office where Mike Norton had negotiated the Rockwell deal thirty years before, that the grand jury documents were missing.

“Can you imagine that?” says McKinley. “The Justice Department has a long history of losing stuff. They lost all kinds of stuff…plutonium, reports.”

And some things never change, he notes. When the grand jury was sent home back in 1992 and its files first sealed, the head of the Department of Justice was William Barr. Today, Barr is again the attorney general.

Lipsky, who was transferred to the FBI’s Los Angeles gang unit not long after his investigation of Rocky Flats, is now a private investigator who continues to push for the release of the real story about Rocky Flats. When he heard that the documents were missing, “the only thing I could do was laugh,” he says. Brenton’s email estimates that “60-some boxes are not physically in our office space now.” Lipsky’s agents filled many times that many boxes with documents seized during the raid at Rocky Flats.

According to Brenton, his office had custody of the requested documents until at least 2004. He’s now going through boxes of documents from linked cases, such as whistleblower Stone’s suit against Rockwell, and the Cook class-action litigation that finally found victory and a $375 million settlement in Kane’s courtroom, to see if they were misfiled.

“It is incidents like this that continue to foster uncertainty and fear within the communities that are the most impacted,” Polis’s office says of the missing grand-jury documents. “Our administration is committed to government transparency and public access to information. That’s why our Department of Public Health and Environment recently requested that these records be unsealed for the public.”

The Rocky Flat National Wildlife Refuge includes the remains of an old ranch.

Westword

For a time, there was a stash of grand jury documents at U.S. District Court Judge Richard Matsch’s courtroom. At one point, the grand jurors had petitioned Matsch to allow them to tell their story; that request was denied, and Matsch passed away this spring. Judge Finesilver had relevant documents, too; before he died in 2006, he gave 180 boxes of records to the Denver Public Library, with the stipulation that they be kept closed until 2009.

That August, a librarian began cataloguing the contents, then ran across two boxes holding various forms of the grand jury report marked “Not for public release.” He called the clerk of the U.S. District Court to ask if the documents could be made public. Instead, the clerk picked up the boxes and demanded that anything else that surfaced involving Rocky Flats be sent to the court.

The missing grand jury materials are not the only documents devoted to Rocky Flats, of course. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment still has voluminous files, including a giant binder detailing all the different chemicals once used at the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Plant. For a time, Front Range Community College hosted a Rocky Flats Reading Room, though much of the materials are now in the University of Colorado archives, which has a “wealth of information,” according to David Abelson, executive director of the Rocky Flats Stewardship Council. “Walling off these documents from public view creates an impression that there’s a lack of information regarding management of the site.”

That impression is misguided, he thinks: His group includes representatives from most of the local governments around Rocky Flats, all but one of which supports recreation at the refuge. Still, in June the council passed a resolution against allowing fracking near the plant, and it’s keeping an eye on three studies being done of environmental conditions at the refuge, the results of which are due this fall. The current samples will be compared to historic samples…if those can be found.

For now, Mellen is drilling down into the case of the missing documents. On July 31, she filed a motion asking the judge to give the U.S. Attorney’s Office thirty days to find them. “I actually believe it’s a bigger number of boxes than that,” she says of Brenton’s estimate. “But right now, I’d be happy with that.”

Rocky Flats isn’t Chernobyl, but this could still blow up.