Travis Cantonwine

Audio By Carbonatix

Eighteen-year-old Travis Cantonwine is the editor-in-chief of the Delta Paw Print, the student news publication at Delta High School. He hopes to become a professional journalist after he finishes college, which he’ll start in the fall at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs – but he’s already learned some tough lessons about the news industry.

He got into the newspaper business because he wanted to be heard…but when it looked like the school district might start censoring the student paper, he silenced it until officials backed off.

In 2019, the Colorado Legislature passed a bill requiring schools that wanted to receive funds from the Comprehensive Human Sexuality Education grant program to implement a sex-education curriculum that did not emphasize abstinence as the primary form of preventing pregnancy and didn’t use stigmatizing language when teaching about gender stereotypes, sexuality or transgender people – if schools chose to discuss those subjects.

In the spring of 2021, the impacts of that bill became clear in Delta County when the school district proposed a curriculum that adopted some of the new, more comprehensive measures. Worried that their children would learn more about sexuality than they wanted them to, some parents protested even as local LGBTQ groups rallied in support of the proposal. Eventually, the school board voted it down.

That May, Cantonwine reported about the controversy in the Delta Paw Print and penned an opinion piece from his perspective as an LGBTQ writer. The school didn’t like the column, he recalls.

“There’s no real evidence I have to corroborate that it’s a direct response to that article, but immediately after the article was posted, the [school] wanted to start putting a prior-review clause in our policy,” Cantonwine says, adding that the school cited a district policy that allowed review of controversial articles by school administrators.

He worked with the Student Press Law Center over the summer and put the Paw Print on hiatus until the school board revised its policy to remove the threat of censorship.

Mike Hiestand, senior legal counsel for the SPLC, which is headquartered in Virginia, says Cantonwine is fortunate that he lives in Colorado. This is one of fifteen states that has a student free expression law that protects student speech in public schools.

“One of the first questions I ask if somebody’s calling…is, ‘Where are you calling from?’ Because once they tell me that they’re from Colorado, usually the news is pretty good that at least the censorship part of it is probably not something that is legally supported, and we can usually push back a bit on it because of Colorado’s law,” Hiestand says.

“We saw an enormous jump in the amount of censorship taking place and the type of censorship taking place.”

That law was passed by the legislature in 1990, after the U.S. Supreme Court issued its Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier decision, which gave student journalists much less freedom on a national level. Before that, the prevailing law was derived from Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District and dictated that students had the right to make their own editorial decisions unless their speech was unlawful or would significantly disrupt normal school activities. After Hazelwood, the bar for censorship got lower: Schools were given the discretion to censor speech if they had a reasonable educational justification.

The problem is that schools can define “reasonable” however they want, Hiestand points out.

“If school officials can censor something simply by saying that it’s poorly written or inconsistent with the shared values of a civilized social order, you kind of flush the First Amendment down the toilet,” he says. “It’s not a very high bar.”

Fortunately for students in Colorado, the legislature agreed with Hiestand and essentially enshrined the level of protection that Tinker had given students into state law.

Hiestand started the SPLC in 1989 after the Hazelwood decision; in its first few years, the organization received about 500 calls each year asking for help, he recalls. Ten years later, it reached its peak, with 2,500 requests for help annually. Now that number is lower, though there are still enough calls to keep the center busy.

“We saw an enormous jump in the amount of censorship taking place and the type of censorship taking place,” Hiestand says. “Many student media programs, particularly in states where they didn’t have state legal protection, just disappeared.”

That’s not the case in Colorado, which Hiestand says still has a flourishing student journalism network in its public schools – though it’s still legal for school administrators to read student publications before they go to press as long as they don’t intervene in the contents. That’s what concerned Cantonwine. Hiestand says he urges students to at least try to make the case that such prior review is a bad journalistic and educational practice, and the Delta County School District seems to have listened to that argument.

Last fall, the district amended the policy to allow only the newspaper advisor to review student work before publication, not administrators. Kurt Clay, assistant superintendent for the Delta County School District, says the change was prompted by Cantonwine’s article, and maintains that student journalists who write controversial stories, rather than school officials, have ownership of those stories.

With that ownership established, the Paw Print began publishing again in November.

“It’s the freedom to make the decisions, but it’s also that responsibility for making those decisions,” Hiestand says. “If a student editor knows that he or she is on the hook for making particular decisions, they’re gonna put some thought into that in ways that they might not otherwise do. I’m delighted to hear that the school officials, who often aren’t so willing to listen to those sorts of arguments…were willing to do so in this case. It really does make a difference.”

In 2020, Colorado’s student free-expression law was updated to protect advisors as well as students. According to Hiestand, SPLC had identified a trend in which schools targeted advisors rather than students when they weren’t happy with student journalism, since students were explicitly protected by law but advisors weren’t; the update seems to have helped mitigate that problem. At Delta High School, that advisor is Kelly Johnson, who declined to comment for this story.

Despite Colorado’s relatively strong protections for student journalists, Hiestand says cases in the state still come up a few times a year because turnover among students is naturally high. Even a student who works for a school publication all through high school is still gone after four years, and many students don’t get into student journalism right away.

Delta High School is home to about 600 students.

Travis Cantonwine

That was certainly the case for Travis Cantonwine. Now set to graduate on May 22, he only got into journalism at the start of the 2020-21 school year and was selected as editor-in-chief, despite his relatively new status on staff, because he’s one of the few students who plan to pursue journalism as a career. He started out with a splash, writing about Decolonizing Delta County School District.

In 2020, former Delta County high-schoolers Marisa Edmondson and Jordan Evans, both women of color, founded Decolonizing Delta County School District and sent a letter to the district describing how it could be more inclusive and better support students of color. Their ideas included a suggested reading list of authors of color.

Dennis Anderson works for Wick Communications as the publisher of the Delta County Independent and the Montrose Daily Press. He’s also the publisher of the Mat-Su Valley Frontiersman in Wasilla, Alaska, and oversees all Wick operations in Alaska. Although Anderson says he doesn’t make any editorial decisions for the papers for which he’s responsible, he occasionally writes columns for them, including a September 2020 piece about Decolonizing Delta County School District that took issue with the organization’s suggestions for which books teachers should read to students. Anderson wrote that it reminded him of banning certain books; he didn’t approve of shaping school curricula with either method.

Cantonwine thought someone should respond to that, and he spoke with Edmondson for a Paw Print podcast episode about the goals of the decolonization movement. He also wrote a column of his own for the Paw Print that took aim at Anderson’s column. “If you think that diverse, new additions will downplay the same white authors, then you have a slight understanding of the emotions associated with those who have not seen themselves in a book at school their whole life,” he wrote.

Cantonwine pointed out that Anderson is white and may not have an understanding of why anti-racist teaching or a more inclusive curriculum is needed in schools. Cantonwine, who is also white, says he tried to make it clear in his column that he wasn’t attacking Anderson as a person but was concerned with the way the local media was covering the decolonizing group and just wanted to communicate its goals.

But Anderson responded with a second column, in which he discussed his upbringing in Delta County – he’s a graduate of Delta High School – and his experiences with prejudice, urging readers to reserve judgment based on skin color.

“[Cantonwine] came out with his column…saying that I am an older white man and don’t have a clue,” Anderson recalls. “My next column was saying, basically, you never know what a person goes through just because maybe their skin color isn’t evident of what their culture is. My point was, my mother was German. … In the ’70s, when I was a kid, when people would find out that my mother was German, they were pretty cruel.”

People would call him a Nazi simply because of his mother’s heritage, Anderson wrote.

After Anderson’s second column, Cantonwine says he was the focus of criticism that made him feel even more isolated at school. “I’ve literally thought about this every single day since it’s happened,” he says. “I think I just wished that he would have actually responded to the issue.”

Anderson says that he believes supporting young journalists is important. In fact, the weekly Delta County Independent prints the monthly Delta Paw Print and the Cedaredge High School student publication, distributing copies with the Independent as a courtesy to both schools. Between editions, Delta High students publish stories on the Paw Print website. “My personal feeling was [Cantonwine is] a very talented writer, and I think, if journalism is what he wants to do for a career, he’ll be very successful,” Anderson adds.

Anderson had also written about the proposed sex education curriculum, pushing back on the idea that the policy would teach students about sexuality before they were ready. Given the nature of small communities, he says, controversial topics like sex education become larger. In Anchorage, where he also publishes a paper, he doesn’t think the subject would attract as much attention as it did in Delta County, which is one-tenth the size.

Delta County has a population of just under 32,000 and is 81.2 percent white and 15.3 percent Hispanic or Latino, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Of Delta High School’s 600 students, about 60 percent are white and about 34 percent are Hispanic or Latino.

“With a smaller community, your press really reaches people, and people are going to talk about your press the next day,” Cantonwine says, adding that he doesn’t agree with what he sees as the conservative bent of the Independent.

“I end up looking at the news every single morning,” he explains. “They’re not really going to get a grasp of a true diverse voice, and it’s just something that’s really been hard to get used to, especially when controversies about LGBTQ issues come up. I always get confused. I’m like, ‘Why don’t you just talk to gay people? Why don’t you just talk to Black people?’ That’s what I did when I reported on Decolonizing DCSD.'”

Still, the value of local journalism, particularly in small counties, is something on which Anderson and Cantonwine can agree.

According to Anderson, both liberals and conservatives think the Independent is biased against their views. “We’ve faced the same thing most of the newspapers across the country face,” he says. “With every story, if somebody doesn’t like the subject or has some kind of a political case against it, it’s always, ‘You’re writing from a liberal viewpoint,’ or ‘You’re editorializing the story,’ which is not true. I’m a pretty conservative person, so to be called a liberal, a communist, a socialist by people that live in my own hometown…it’s challenging, for sure.”

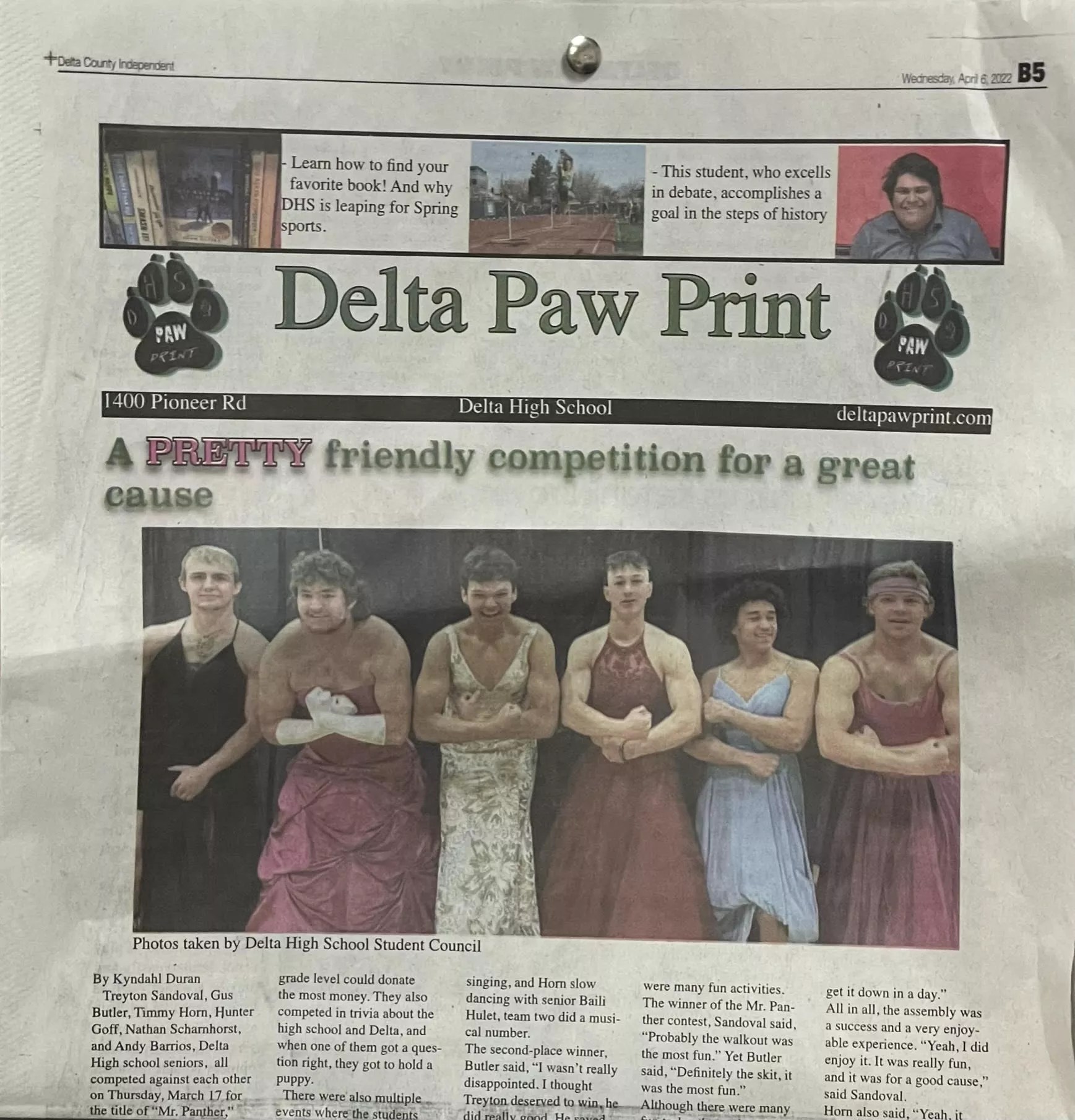

April’s edition of the Delta Paw Print.

Travis Cantonwine

So is working on a school paper in Delta, where Cantonwine has gotten a crash course in those challenges during his two years at the Paw Print.

Hiestand is encouraged by students like Cantonwine, and urges other high school journalists to write about any topic without fear.

“We need young voices in particular,” he says. “They occupy a unique place: A sixteen-year-old’s take on climate change is going to be much different than my take as a fifty-year-old, and so we need those voices, we need those fresh sorts of perspectives. It’s healthy for society, and it’s an important thing for students to get their message out – because if they don’t do it, nobody else will.

“Take advantage of the law,” he urges, “and say what you need to say.”