Chris Walker

Audio By Carbonatix

The Homeless Advocacy Policy Project at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law has released a report that shows how some municipal ordinances in Colorado disproportionately affect homeless populations.

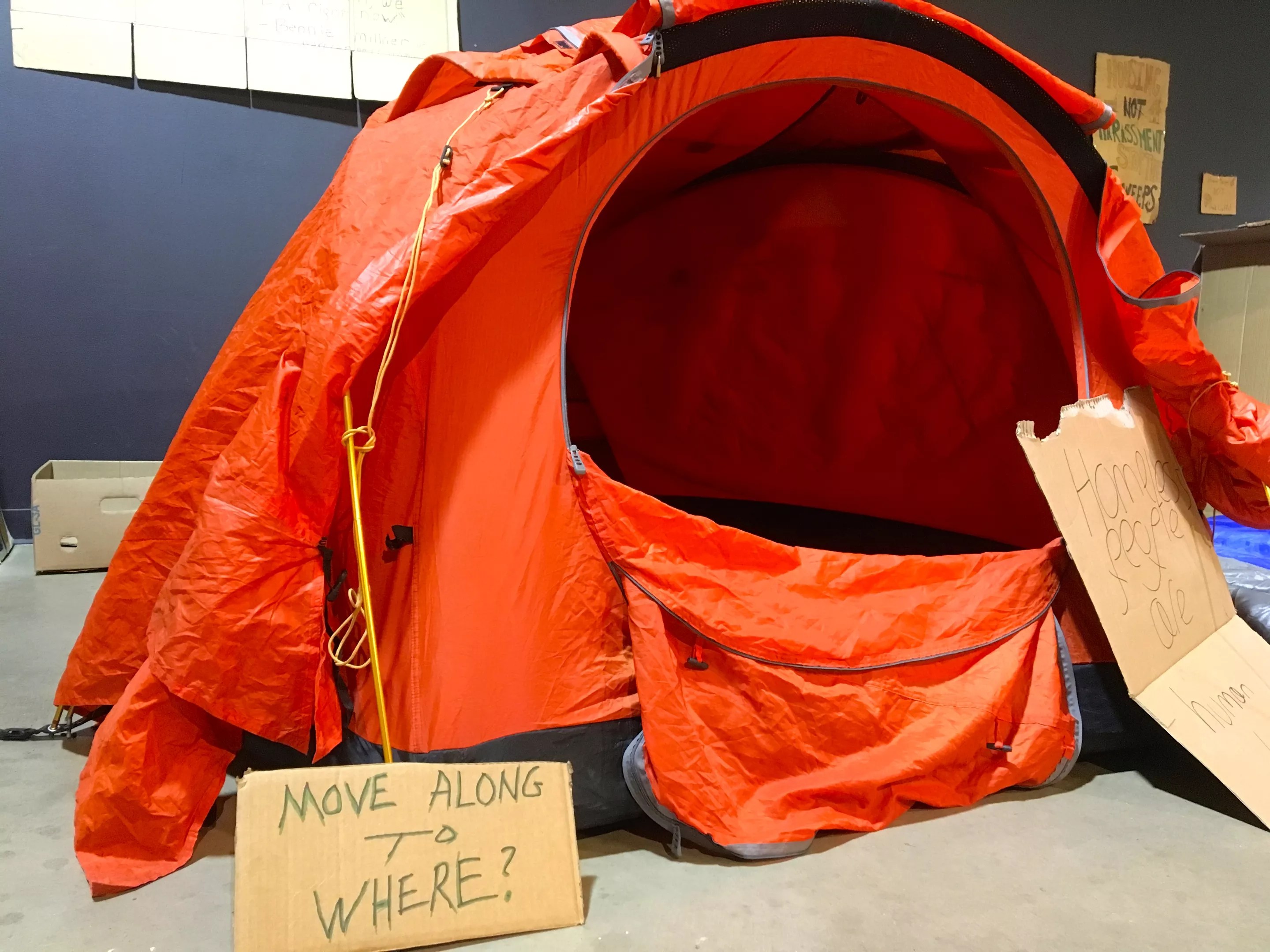

Researched and compiled by DU law students, “Too High a Price 2: Move On to Where?” is a followup to a study released in February 2016 that calculated how much money large cities in Colorado were spending to enforce laws that criminalize homelessness (which include such ordinances as camping bans, park curfews, limits on panhandling and bans on public urination).

The 2016 study raised concerns about the use of city resources with its eye-popping tabulation that five cities — Denver, Colorado Springs, Boulder, Fort Collins and Durango — had spent a combined $5.1 million enacting anti-homeless ordinances from 2010 through 2014. The study inspired state lawmakers to introduce Right to Rest bills for three sessions in a row at the State Capitol that aimed to do away with many of the anti-homeless ordinances mentioned in the DU report. The Right to Rest bills were voted down in committee every year, largely along party lines.

In the follow-up report released today, the Homeless Advocacy Policy Project found that Denver has added four ordinances to police its homeless population and Colorado Springs has added one since 2016. Denver’s new laws limit gathering in public places, camping in parks, smoking on the 16th Street Mall and obstructing public areas.

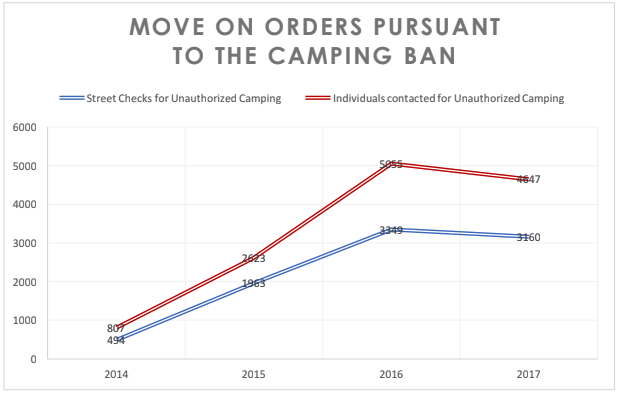

Beyond the number of citations, the law school’s 2016 report didn’t have detailed enforcement statistics for Denver’s urban-camping ban. In 2016, Westword obtained that data under an open-records request and found that even though the city was only issuing a handful of citations each year, police officers frequently used the camping-ban ordinance to “move along” individuals experiencing homelessness through verbal commands — or what DPD calls “street checks.”

While few citations or arrests are made under Denver’s camping ban, thousands of move-on orders are issued under the ordinance.

Too High a Price report

This more nuanced enforcement data is prominent in the new DU report. A summary of the report’s key findings notes: “Denver’s use of move-on orders has skyrocketed at an alarming rate. In 2016 alone, Denver law enforcement made contact with over 5,000 people in move-on encounters. Denver police increased its contact with homeless individuals through the use of street checks by 475% in the span of three years.”

The report doesn’t calculate how much money and time the Denver Police Department uses to conduct regular “street checks,” but it does make an impassioned case against move-on orders.

“The move-on orders result in further isolation and ostracism, driving homeless individuals into locations that have higher potential for violence, are detrimental to their health, and force them away from centrally-located

resources and outreach workers,” the report’s authors note.

The report also emphasizes the importance of tracking enforcement of the camping ban since the city is facing a housing crunch and, save for Denver’s consistently crowded shelter system, there is nowhere for people experiencing homelessness to rest in public without being targeted by police, who can enforce fifteen anti-homeless ordinances.

“These ordinances typically prohibit life-sustaining behaviors that homeless individuals need to survive, such as sitting, sleeping, camping and panhandling in public places,” says Nantiya Ruan, a DU professor who oversees the Homeless Advocacy Policy Project.